As Chris entered adolescence, the operations, the secrecy, and the judgemental language of the Church weighed heavily on him. Being excluded from playing sports at school and mistakenly believing he would die young, he felt very different from other boys. But with a change of school at 16, a feeling of hope began to creep in.

Wonder years

Words and artworks by Chris Northaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Serial

Adolescence is a time when most boys seem to be enjoying their “wonder years”, with testosterone-accelerated physical development, new friendships and growing self-esteem. By contrast, my life was marked by secrecy and confusion. None of my traumatic intersex-related surgeries were ever explained to me, but I knew I was very different. I had my “I wonder” years.

During a PE lesson when I was aged 13, the headmaster noticed I was developing breasts; I was acutely embarrassed by them. Until I accessed my childhood hospital records in 2018, I was unaware my school had contacted the hospital or even knew of what I was going through medically and “the secret” I lived with. I then underwent more surgery.

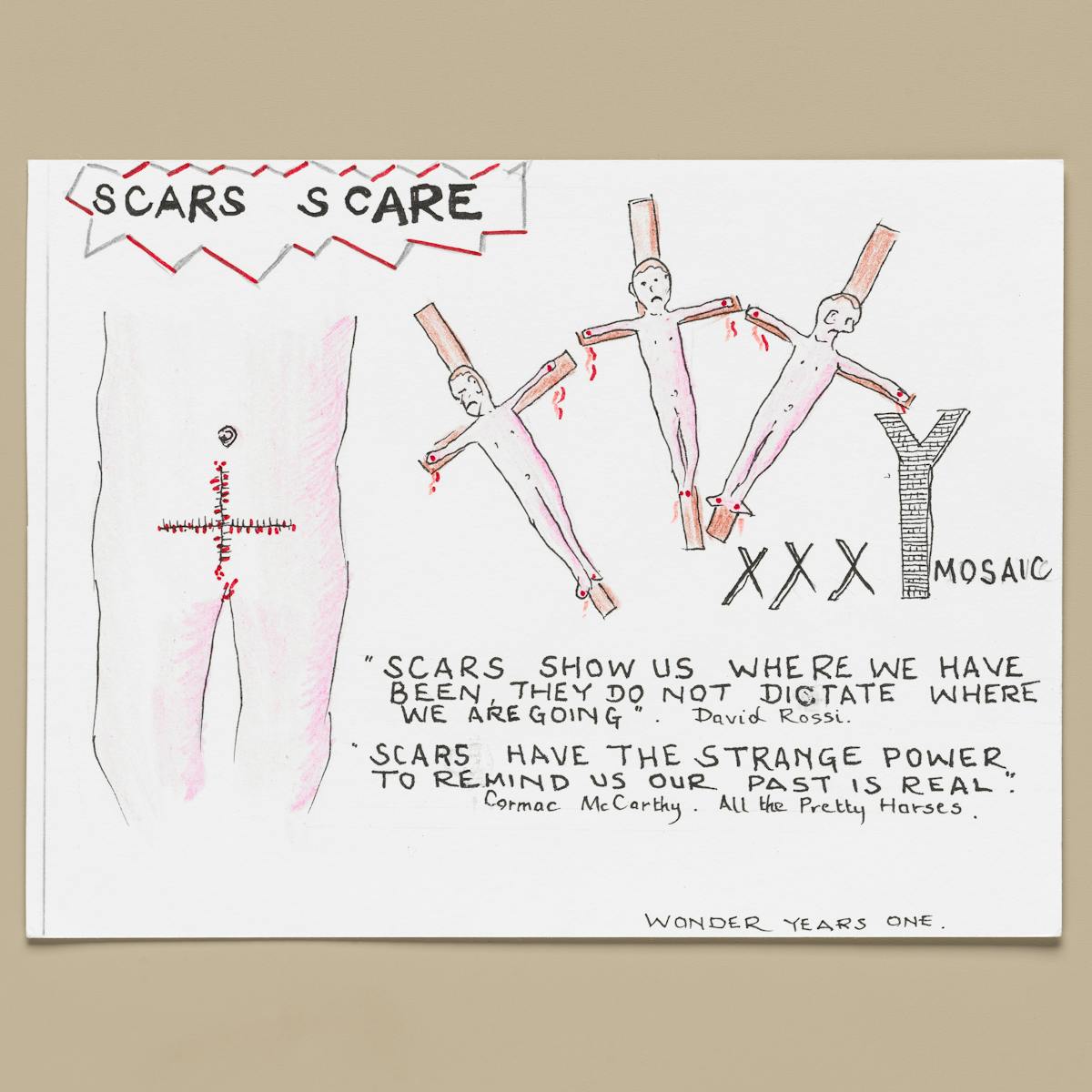

Doctors discovered female reproductive organs with an ovotestis and gave me a total hysterectomy. I was left with scars running from my navel to pubis and criss-crossing left to right, like the sign of a cross. An earlier intersex diagnosis was finally confirmed, and a DNA swab test clinched that I was genetically female, though I had been designated a boy at birth due to what looked like a micro-penis.

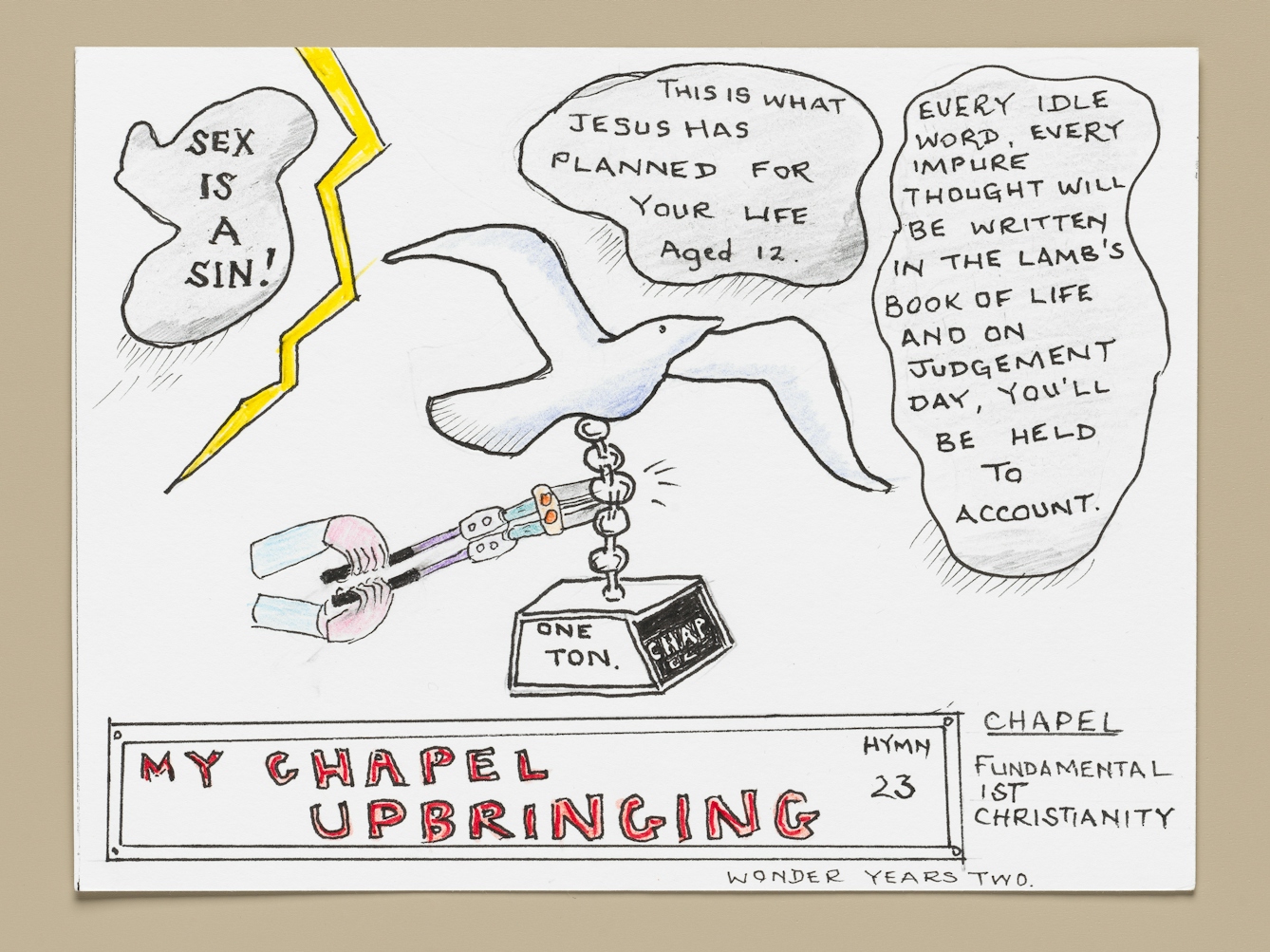

‘My chapel upbringing’ by Chris North, 2023.

Going on testosterone

Since I was unable to manufacture my own testosterone, I was prescribed two 10 mg tablets daily to stimulate male characteristics. My father firmly said, “You’ve got to take these for the rest of your life!” It was his way of coping. Nobody explained why I was taking them, and I felt bewildered, unable to ask.

As the prescribed testosterone kicked in, I built some muscle, my voice broke, I got acne and grew some facial hair. I had micro-erections and enjoyed a limited and enigmatic sexual pleasure.

My fundamentalist chapel teaching said that pleasurable sex was sinful. I faced a dilemma: a little masturbating heaven or condemned to a miserable hell? I rejected the second.

I’d gleaned a skewed and very limited knowledge of sex and anatomy through National Geographic magazines, chapel, school sex-education chalkboard line drawings and secretive conversations with classmates. When a doctor asked if I wanted plastic balls, I had no idea what he meant and said, “No thanks.”

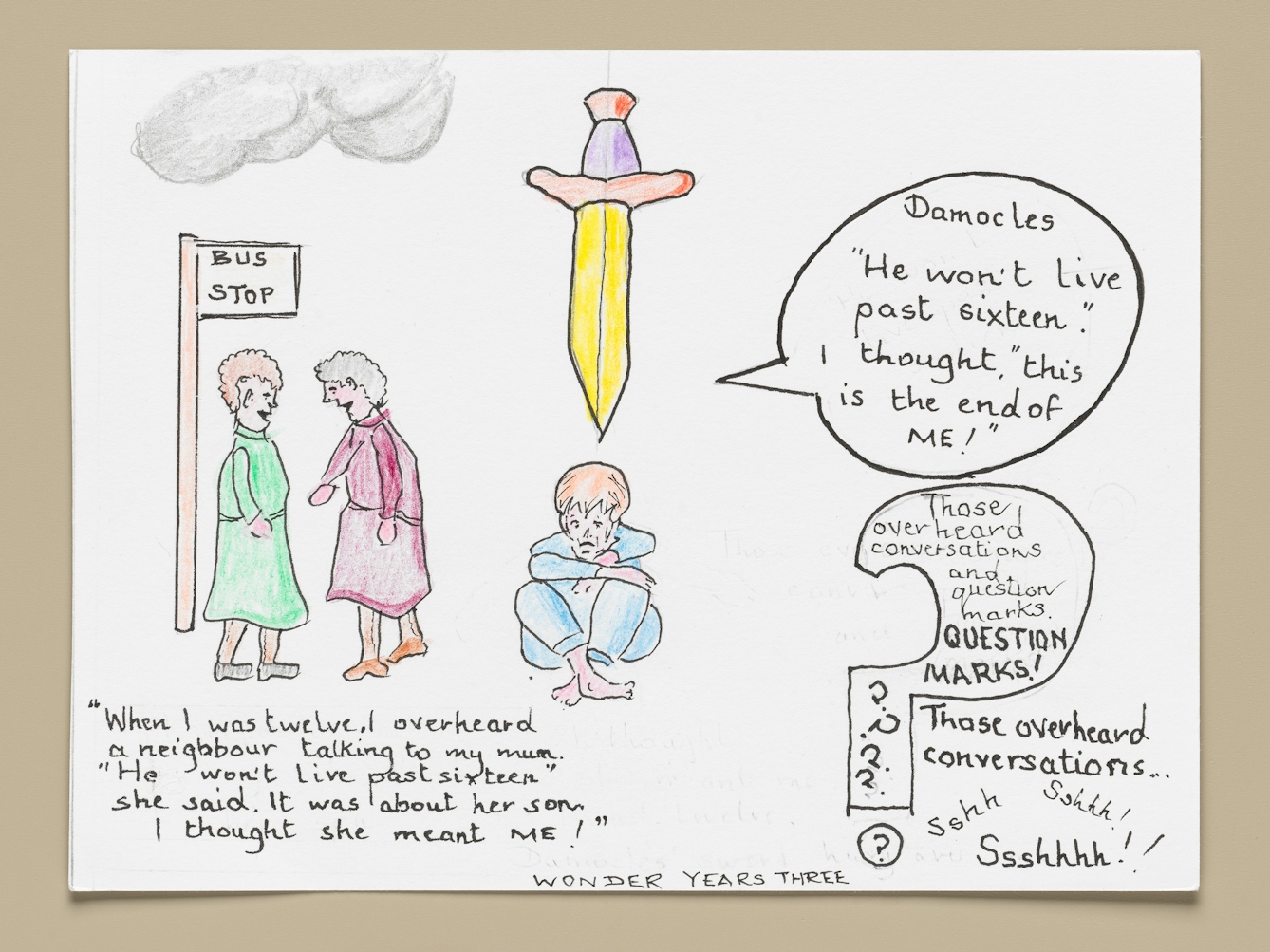

‘Those overheard conversations’ by Chris North, 2023.

A time of trauma

But the differences between my life and that of my peers went beyond the biological. I also missed out on a great deal of school life.

Even after returning from the prolonged absences due to my surgery and recovery, I was excluded from football and PE because of my scars. During football lessons, teachers told me to walk around the field for an hour, alone.

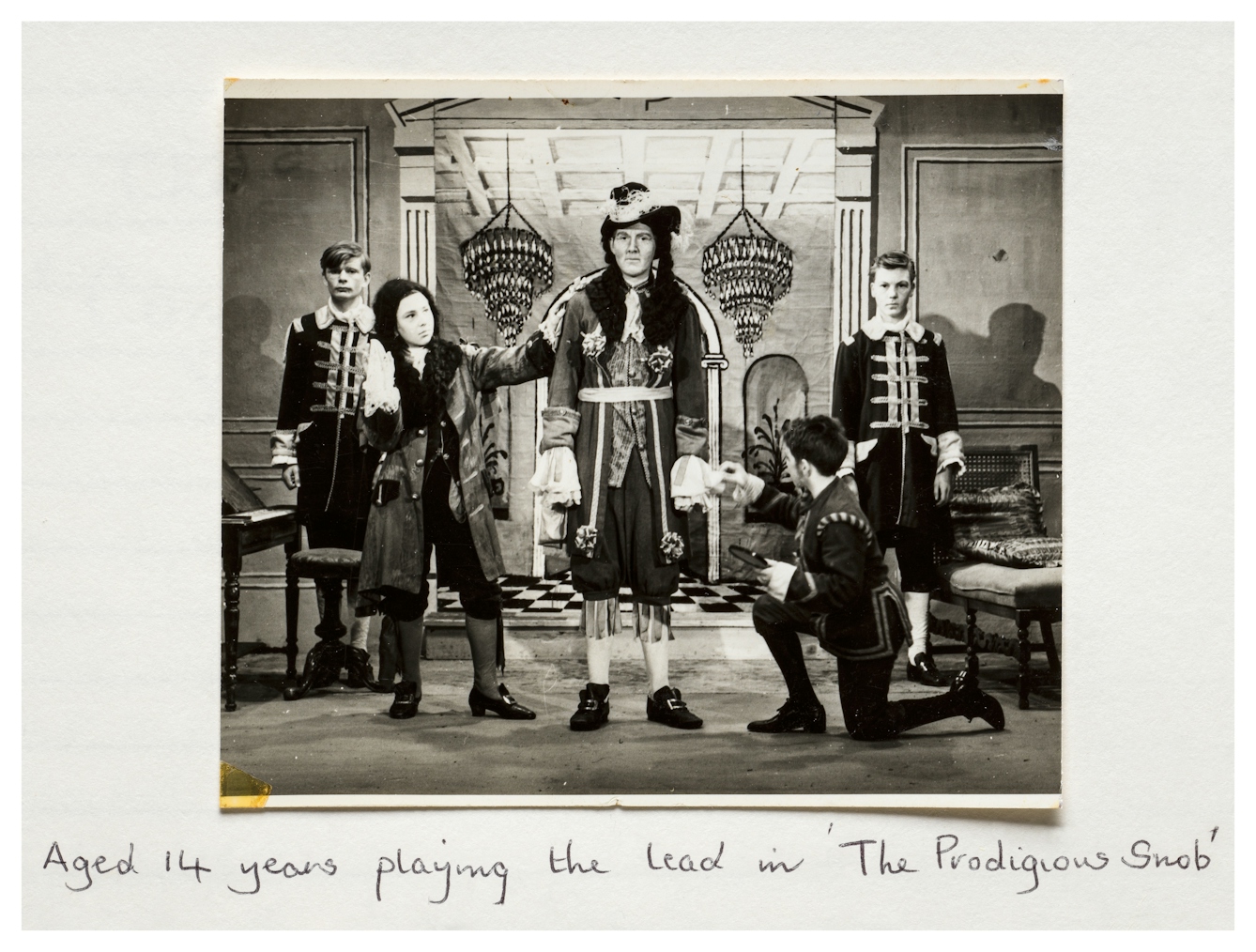

Drama absented me from myself for a while. I became part of a community, felt valued and had a vehicle for my natural creative spark. The teacher recognised this and gave me the leading role in the school’s Christmas production. I glowed and made new friends. At 14 I joined an amateur theatre company. I also enjoyed the after-school dance club but felt unable to ask any girls out.

The confusion, secrecy and pain of this time affected my mental health.

In my early teens, I overheard a neighbour say to my mother, “He won’t live past 16.” Because of all the unexplained surgery and trauma that I’d endured over the past 13 years, it didn’t occur to me that she was talking about her own son; I thought she meant me. The end hung over me. I didn’t bother too much about exams because I didn’t expect to live far beyond them.

I was given psychological tests, including IQ and Rorschach ink-blot tests, which unsurprisingly showed a “considerable amount of anxiety”. I never recalled being asked how I felt, though, only tested. It wasn’t until 2018, when I accessed my childhood medical records, that I found I had blocked most memories of my interactions with the child psychiatrist. This sort of dissociative amnesia is often linked with trauma.

Chris aged 14 playing the lead role in the school production of 'The Prodigious Snob'.

Cutting loose and breaking away

In late 1962, aged 16 and with early adulthood on the horizon, I was discharged from Great Ormond Street Hospital. No plans were made to register me at another hospital; I was cut loose, not knowing I was intersex, and I was now on regular hormone-replacement therapy (testosterone). School changed too, because I moved to an all-boys sixth form, unexpectedly escaping Damocles’ sword by surviving past my 16th birthday, and performed moderately well. Drama helped my insecurities, and I began to develop self-esteem.

I’d begun breaking free from the chapel as I became a teenager. The congregation was older, and I found the emphasis on sin and guilt weighed heavy. Words such as “The sins of the fathers are visited on the children” and “Are you washed in the blood of the Lamb?” were condemnatory, damaging and had echoes of my catheter bag full of blood.

Around the time I left school, the shackles of chapel finally broke, and the ton weight fell to the ground; I was almost free. I didn’t discuss my rejection of the Church with my parents, though, and it became another secret.

I gained five O levels and thought about my future. Because of my early interest in electronics, my parents believed I’d pursue that, but I needed to be creative and work with people and so I decided to become a teacher. Despite all the uncertainty and confusion in my life, I was determined to both find and make my place in the world.

About the author

Chris North

Chris North is an author, independent scholar, creative arts facilitator, intersex advocate and activist. He’s been a teacher, social and community worker and is now a storyteller. He shares his powerful personal experience to provide much-needed “lived historical intersex testimony” and works hard for other minorities and those marginalised by society.