Since the heyday of eugenics in the early 20th century, governments and the medical establishment have tried to seek out ways to reduce the number of babies born with disabilities. Historian Jaipreet Virdi explores this world, in which DNA testing and gene editing are hailed as the most sophisticated tools, but from a different angle: perhaps human societies should consider a radical change of attitude.

In a world where a “designer baby” is no longer hypothetical, this quote from the 1997 film ‘Gattaca’, “We now have discrimination down to a science,” has never been more relevant. Continuing developments in the field of gene editing could mean predispositions to hereditary conditions and disabilities such as Down syndrome or Parkinson’s being eliminated at the level of the gene.

DNA ancestry tests have become popular over the last decade. But do they actually tell us anything vital about who we are? Do we even need to know the details of our ancestry to understand our identities and our place in the world? Not all disabilities are marked on our genes. My deafness, which is a crucial part of my identity, is not hereditary, so it wouldn’t show up on a DNA ancestry test, nor would the chronic illnesses that define my disabled experiences.

Modern eugenics and disability discrimination

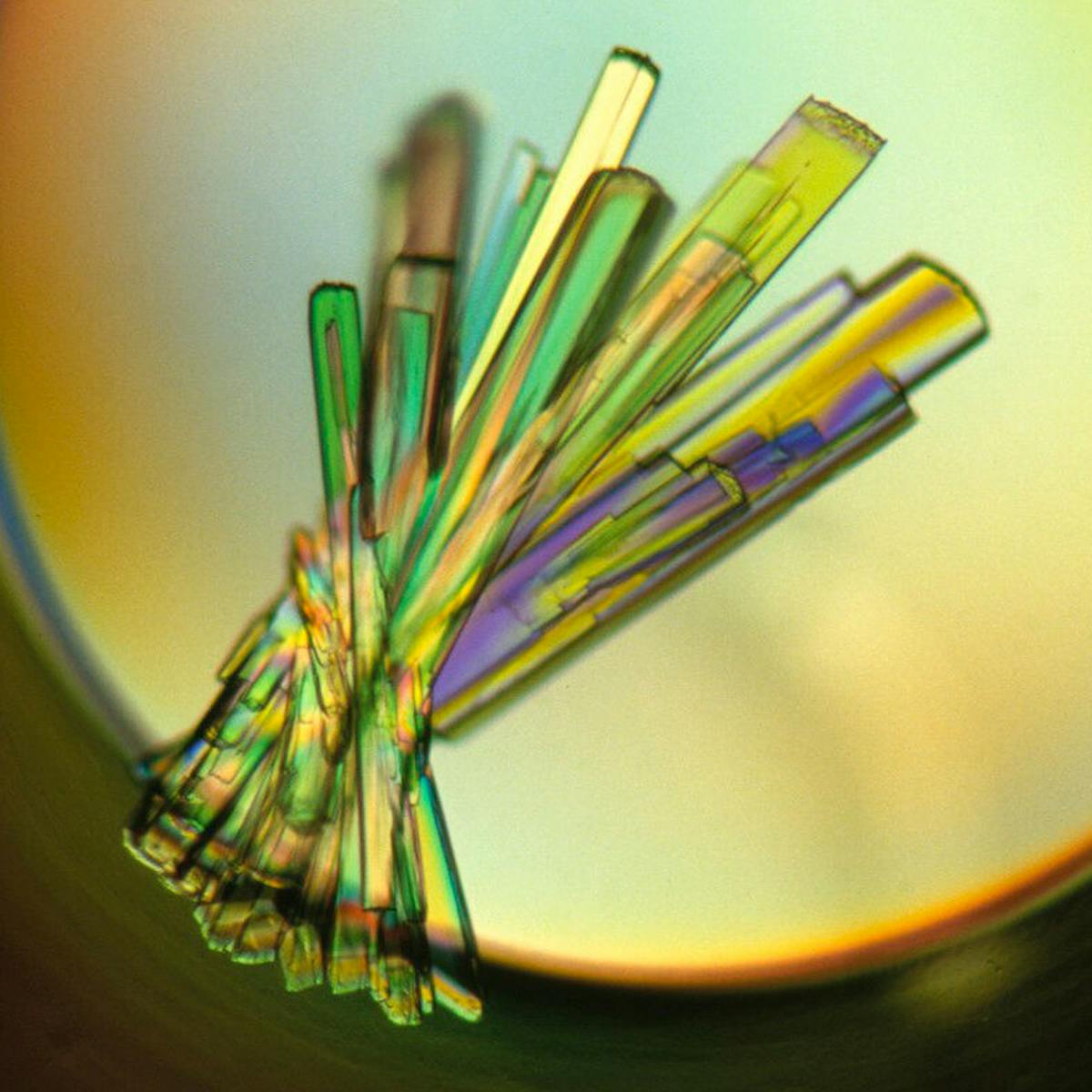

Using “genetic scissors” in the form of CRISPR technology offers the suggestion that we could edit out a gene-linked condition.

But disabled philosophers and people who work in bioethics proclaim that this is a problematic attempt to pick apart ‘disease’ and ‘person’. Genetic conditions are a fundamental part of disabled living; they add variation to the human experience, and these differences provide insight for conceptualising more inclusive technologies and spaces – such as in healthcare.

Arguing that certain conditions are to be eliminated is equivalent to claiming that disabled lives are not worth living: that is, implementing a form of what philosopher Rosemarie Garland-Thomson calls “velvet eugenics”.

The message is harmful: if people cannot abort an embryo tested for a hereditary disabling condition (the shifting legal landscape in America is limiting choice), and if it’s too complicated or expensive to offer social services for a disabled person, then we must eliminate at the level of the gene.

Thinking like this intrinsically associates disability with deficiency – which contradicts the varied richness of disabled living.

“Not all disabilities are marked on our genes. My deafness, which is a crucial part of my identity, is not hereditary.”

What does it mean for genomics then, if we eliminate disability in the quest of human perfection? Such eugenical approaches – and yes, they are totally eugenics – would remove a vibrant part of our culture and society.

Disabled bodies are imperfectly perfect and will always be here.

Disabled people have long been at the forefront of civil rights and movements, the first to literally throw their bodies on the line for human rights. And as disabled activist Dom Evans tells us, “Disabled people will never go away because new genetic anomalies will lead to new disabilities. It is fruitless to attempt to rid the world of disabled people, because it is never going to happen.”

In ‘Gattaca’, Jerome Morrow (played by Jude Law) is born ‘valid’ and without genetic concern but spirals into depression after finishing second in a swimming competition and becomes a paraplegic after attempting suicide. The narrative echoes the harmful message that disability is worse than death. Yet as disabled people testify, the harmful aspects affecting their lives tends to be more from social barriers that prevent their full participation in society, rather than from their physical and/or mental disabilities.

Disabled bodies are imperfectly perfect and will always be here.

Official attempts to manage heredity

Despite the impossibility of eliminating disability, and the ethical issues with trying, we continue to turn to science for new solutions for ridding future generations of chronic illness and hereditary diseases.

The idea of eradicating disabilities at the level of the gene has been around for a very long time, since scientists first assessed whether heredity could be bureaucratically managed.

In the US, Deaf schools, for instance, kept records of pupils with family histories of hereditary deafness. By the turn of the 20th century such data collection was replaced by more formalised studies of heredity. Alongside these studies, American government policymakers and scientists alike implemented restrictions on deaf marriages.

“Disabled people will never go away because new genetic anomalies will lead to new disabilities.”

These measures have gone alongside medical attempts to understand the mechanisms of genetic anomalies. Such research has the aim to ‘correct’. Within medical spaces, disability is discussed in terms of how abnormalities need to be prevented or cured, rather than in terms of human variation.

Fear of disability has also shaped the way we think about healthcare and insurance coverage.

Buying into DNA

Today, it’s not only doctors, insurers, corporations and governments looking at DNA ancestry and thinking about disability. People concerned about their reproductive futures or predispositions to genetic disorders might want more information about their ancestry to make informed health decisions.

At-home ancestry tests have become popular for promising to reveal “who you are”. Or at the very least, who you are as outlined in your DNA.

DNA ancestry testing is a billion-dollar industry. Companies have made sales to approximately 30 million people worldwide (though the numbers appear to be declining, likely due to privacy concerns, limited utility and market saturation).

With the ‘objective’ science of DNA, these tests offer consumers information about genealogy and ethnicity, connect distant relatives, and answer questions about ancestry – especially for people who don’t know their background, such as adoptees and descendants of enslaved people or forced migrants.

The limits of ancestry testing

How exactly is the information obtained from these tests being stored or used? These details are not outlined in advertisements, nor do testing kits explain the complexity of DNA ancestry – you can’t always get the information you’re seeking because not everything can be explained at the level of the gene.

We cannot extract race from DNA testing kits. Nor can we surely get a scientifically objective answer about disability from our genes. However, DNA ancestry tests are also increasingly being used for informing healthcare decisions by providing a fuller picture of family history to address potential health risks identified in genes.

“You can’t always get the information you’re seeking because not everything can be explained at the level of the gene.”

The risks of inherited mutations in the BRCA1 and BRCA2 genes, which increase the chances of breast, prostate and ovarian cancer, can guide decisions about treatment, including preventive surgery to lower the risks. Or an African American patient with repeated respiratory infections might learn, for instance, that they have both copies of the CFTR gene – which has a European origin – and thus an increased likelihood for cystic fibrosis.

But DNA ancestry test results are not confirmation of a disease or risk, or even an indication that a person is a carrier, just a suggestion of the increased probability they might be.

Designing a non-disabled future

Receiving test results that suggest a genetic link with a medical condition can be worrisome and confusing – probably even more so when the result indicates the possibility of debilitating disabilities or chronic health conditions. And what do you do with this information when you have it?

23andMe collects data for the purposes of medical research, especially from people with hereditary diseases, to increase their chances of finding genetic causes – and likely a patented treatment – or offer precise medicine.

The probability that you are predisposed to a genetic condition causing disability also includes the probability that it will never occur, but does knowing that possibility change the way you view disability? Will you carefully screen your body for the first signs it is changing, scrutinise partners to ensure they genetically match so recessive traits are not passed on to potential offspring?

You might want to do a test to explore your health via your DNA ancestry. But I’d like you to pause for a moment. There’s a better investment for the future of your health.

Maybe, instead of viewing disability through its negative implications, we can become more open to newfound possibilities to shift away from ableist assumptions and expectations.

If we create our world with “crip futurity” in mind – a world made to be accessible and designed with accessibility in mind – then predisposition to disability wouldn’t even matter, not even at the level of the gene. We would have already made space for acceptance of all variations. And that, perhaps, is the real utopia.

About the author

Jaipreet Virdi

Dr Jaipreet Virdi is a historian of medicine and disability based at the University of Delaware. Her first book, ‘Hearing Happiness: Deafness Cures in History’ is available where books are sold. She is currently working on her next book, ‘An Invisible Epidemic: The History of Endometriosis’.