The definition and diagnosis of hysteria has quite a history. Explore the beginnings of hysteria in Greece, through to animal magnetism, vibrators and, finally, shell shock in World War I.

When it comes to explaining hysteria, you might have heard some variation of the following:

- In ancient Greece it was thought that women’s wombs wandered through their bodies, causing madness (hystera = womb; hysterikos = of the womb).

- Hysteria stems from sexual frustration in women.

- And the one you are most likely to have heard: in the 19th century, women thought to have hysteria were ‘treated’ with vibrators by their doctors.

All of these are simplifications, perhaps even pure misogyny. In fact, the idea of hysteria has changed throughout Western European history: the disease has been a catch-all (tragically) for ailments as wide-ranging as epilepsy, infertility, PTSD, depression and menopause. The simplified urban myths of hysteria make assumptions about the continuity of women’s sexuality. As historian Helen King explains, hysteria is not a single disease entity with a continuous history, nor is it a disease with a continuous set of symptoms.

The ancient Greek doctor Hippocrates, perhaps the first to diagnose hysteria, explained the disorder as “suffocation of the womb” – as the womb moved throughout the body it produced different symptoms in response to its trapped location. One cure was anointing the head with “oil of lilies” and massaging the patient. In ancient Rome, Celsus prescribed bloodletting or cupping followed by the application of hot moist plasters to the genital region. In the ancient text of Soranus (c. 100 CE), the main objective for these treatments was to help with painful or non-existent menstruation.

Sensibility and mesmerism

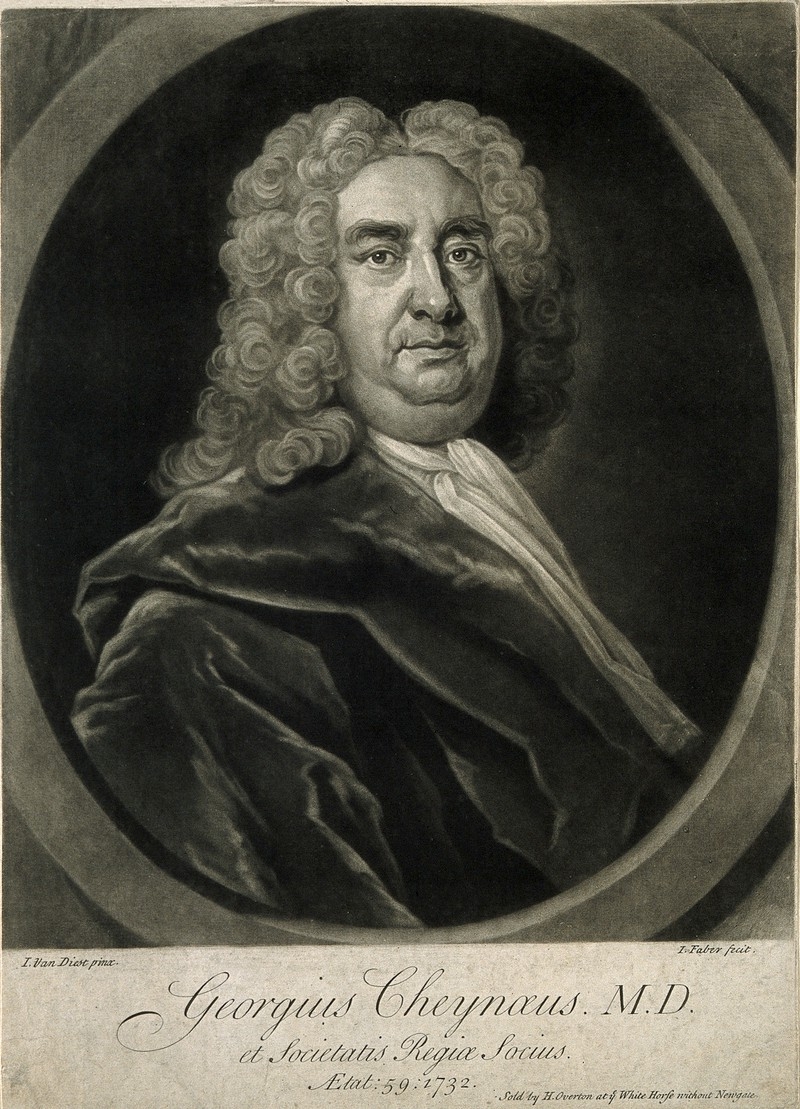

The concept of “suffocation of the womb” persisted for centuries, until the Enlightenment ushered in a greater understanding of anatomical function. Although anatomy was better understood, the comprehension of mental function was still a burgeoning science, as proved by the work of physician George Cheyne, who wrote ‘The English Malady’ in 1733.

Dr George Cheyne: perhaps the first to call hysteria a “nervous illness”

Dr Cheyne attempted to separate the English from their enemies the French, Germans and Spanish (and their malady, syphilis) by saying the English had melancholy, anxiety, nervousness (i.e. not syphilis). Cheyne claimed that hysteria could only happen to intelligent people: “Fools, weak or stupid Persons… are seldom troubled with Vapours or Lowness of Spirits.” He was perhaps the first to call the disorder a “nervous illness”, linking it to functions in the brain and motor system, which were being discovered more and more through dissections and Enlightenment enquiry. Women got the vapours and men had the (wandering) spleen; the whole thing was called “sensibility” (hence Jane Austen’s ‘Sense and Sensibility’).

MORE: Is it possible to accurately diagnose medical conditions suffered in the past?

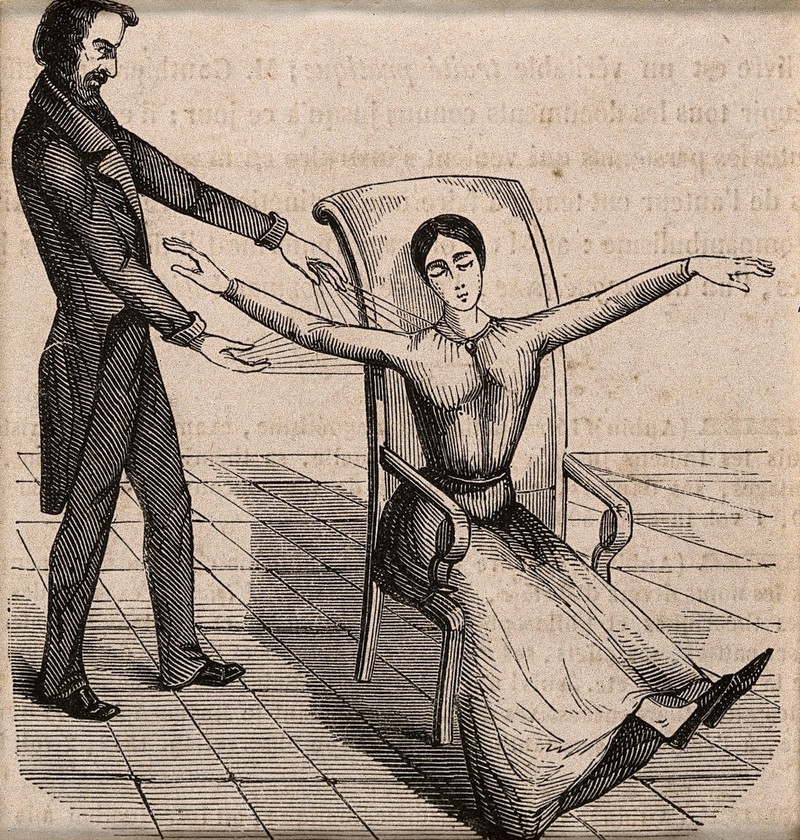

In the late 18th century Anton Mesmer had the cure for all of those aristocrats afflicted with the vapours and the spleen: mesmerism, his own brand of animal magnetism. Animal magnetism was not, at first, seen as potent sexual energy; rather it concerned the energy that flowed through the nervous system and how that energy could be transferred to others as a method of healing. It could be manipulated and channelled from one person to another through massage or transference that looks like the image below:

A Mesmerist using Animal Magnetism on a female patient

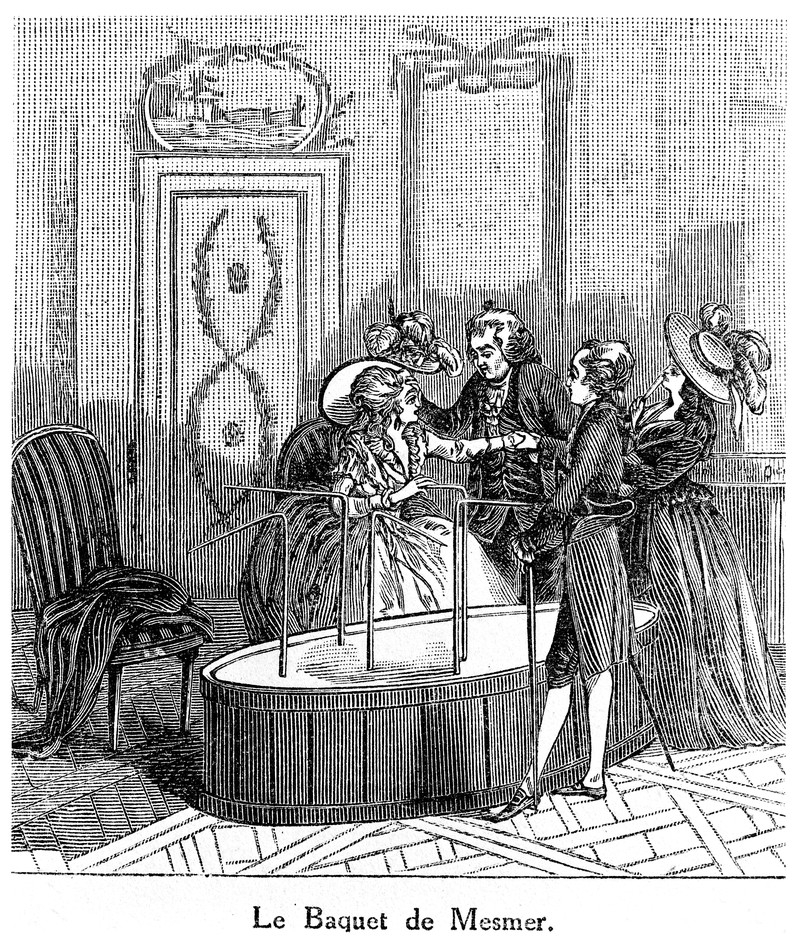

At a Mesmer banquet people would hold onto metal rods that would be lightly electrically charged by Mesmer’s animal magnetism, which would then pulsate through the metal rods, helping to cure the sufferers of their nervous illnesses. Thought to be too sexual when it began to be used in private sessions, Mesmer’s technique was discredited and he was disgraced.

Men and women in a Mesmer Banquet

Victorian treatments for hysteria

In the mid-19th century, Silas Weir Mitchell created the “rest cure” as a treatment of hysteria. Mitchell believed hysteria was caused by overstimulation of the mind, which women could not tolerate because they did not have the capacity. If prescribed the rest cure, a woman would be confined to bed, force-fed rich, fatty foods, massaged, and electro-shocked (in some cases).

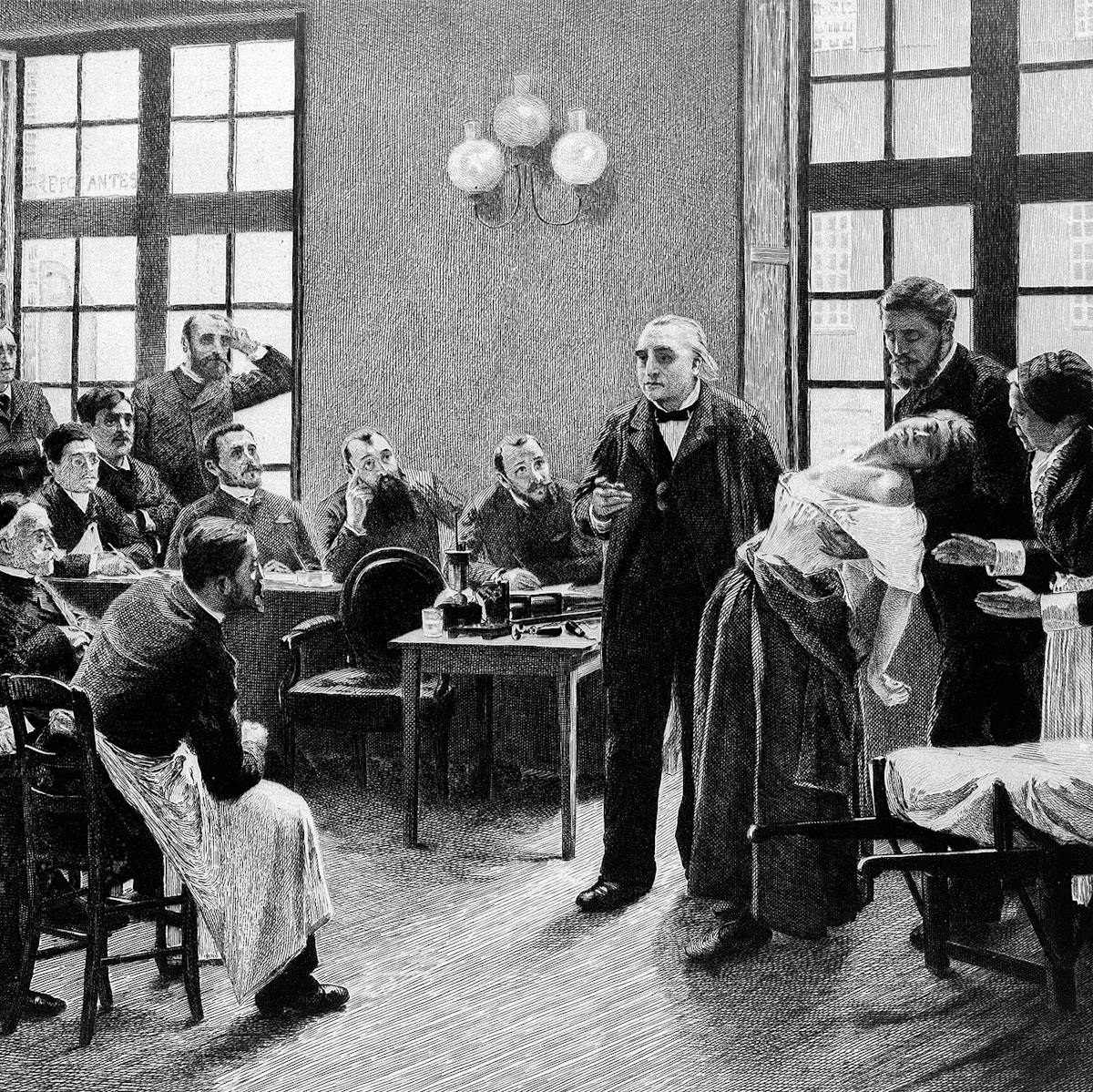

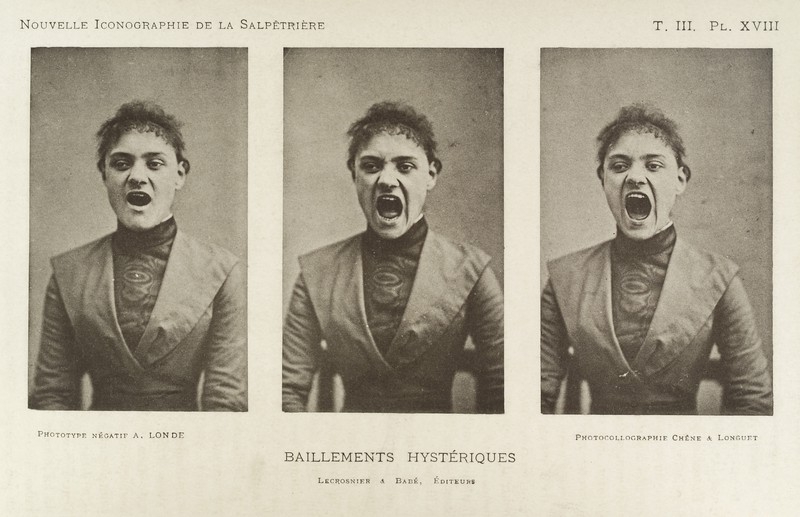

His cure is famously described in Charlotte Perkins Gilman’s ‘The Yellow Wallpaper’ (about her experience at ‘rest’). The gifted neurologist Jean Martin Charcot, who worked at Salpêtrière (a hospital and asylum for the working classes just outside Paris), was absolutely stumped by the “dis-ease”. He attempted to document the symptoms by photographing, drawing and even publicly displaying patients in various states of hysteria in an attempt to find a consistency in the affliction so that he might be able to treat it.

Series of three photos showing a so-called 'hysterical' woman yawning

Some contemporary rumours suggest that doctors like Charcot masturbated their patients with vibrators, performed clitorectomies on them or used the electrocution of the testicles or uterus to cure hysteria; these ideas have since been debunked by several historians, including Leslie Hall. Charcot most certainly did not use these particular torturous abuses as a cure, but he did employ the ovary clamp. Some patients even requested it when they felt symptoms coming on.

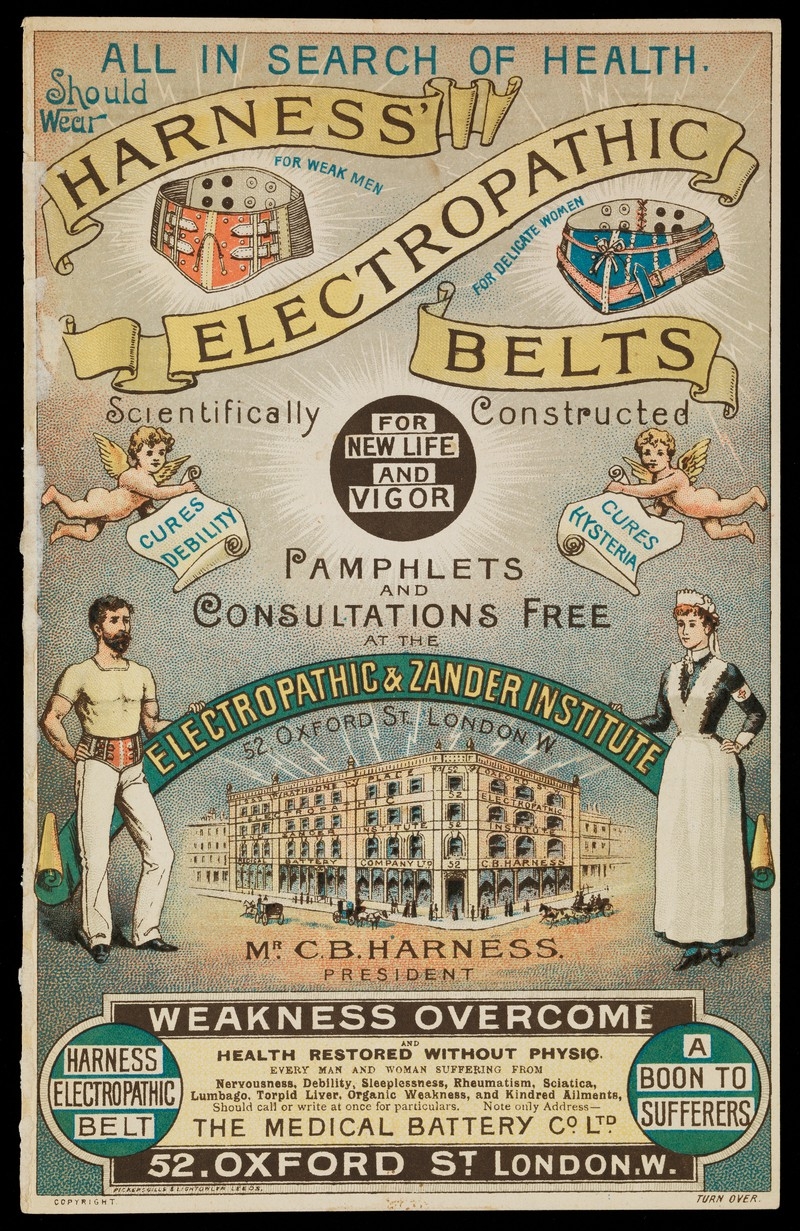

The vibrator cure

So, where exactly did the myth of vibrators come from if the most famous hysterical doctor of the 19th century did not use them to treat patients? The source of this myth is Rachel Maines and her 1999 work ‘The Technology of Orgasm’, which seems to be the only source of this information. It is true that with the evolution and availability of electricity, vibrators were used by doctors to treat patients for all sorts of ailments. Electronic massage was used, but it is highly unlikely it was used to stimulate orgasm (again see Leslie Hall). That’s not to say that people did not eventually use electronic massage for that purpose.

advert for Harness' "Electropathic Belts"

Defining hysteria

The extreme misdiagnosis of hysteria slowed in the late 19th and early 20th centuries because of two major factors: psychoanalysis and World War I. Sigmund Freud’s psychoanalysis had its origins in hysteria: Freud was Charcot’s student. Along with his research partner Joseph Breuer, Freud was able to explain that the physical manifestations of hysteria were not a result of nerves or disorders in the physical body. Instead, physical symptoms were brought on by mental trauma.

Freud and Breuer are the first to assert that hysteria happens in the mind, not triggered by the physical brain, nervous system or the body. Their book ‘Studies on Hysteria’ (1895) introduced the talking cure as a method of treatment for those afflicted with bouts of hysteria.

Shortly thereafter, World War I produced thousands of men with the same symptoms of hysteria; this time it was called “war neurosis” or “shell shock”. The British army alone claimed 80,000 cases of shell shock by the end of the war. Because the victims of this brand of hysteria were primarily men, the experimentation with treatment changed, varying from electro-convulsive therapy to abstinence. The study of mental trauma and its physical results began to be taken as a serious point of focus.

So what is exactly is hysteria? How can we define it? It is mental instability, fits of rage, anxiety; things that can actually happen when you are suffering from an illness or trauma. In 1980, hysteria was removed from medical texts as a disorder unto itself, but it has remained present as a symptom of disease brought on by specific trauma, both physical and mental.

Although it is now seen as a symptom or result of another illness, it has marked women for centuries: their volatile behaviour, their need to be tamed physically, their weak mental constitution. Although the myths of hysteria are fanciful, its real history not only reveals how it has been a tool to control women’s behaviour and bodies, but shows the frightful neglect mental trauma has received throughout the centuries.

About the author

Sarah Jaffray

Sarah Jaffray is an art historian and Visitor Experience Assistant at Wellcome Collection.