Our obsessions are contradictory and multiple: deeply intimate, yet forged by the times we live in. In ‘The Book of Phobias and Manias’, Kate Summerscale offers an A–Z compendium of our fixations, and what they say about us and society. In this extract, she explores how the way we describe our anxieties and compulsions has developed, and the new phobias and manias that are always emerging.

Tracing the roots of our fears and fixations

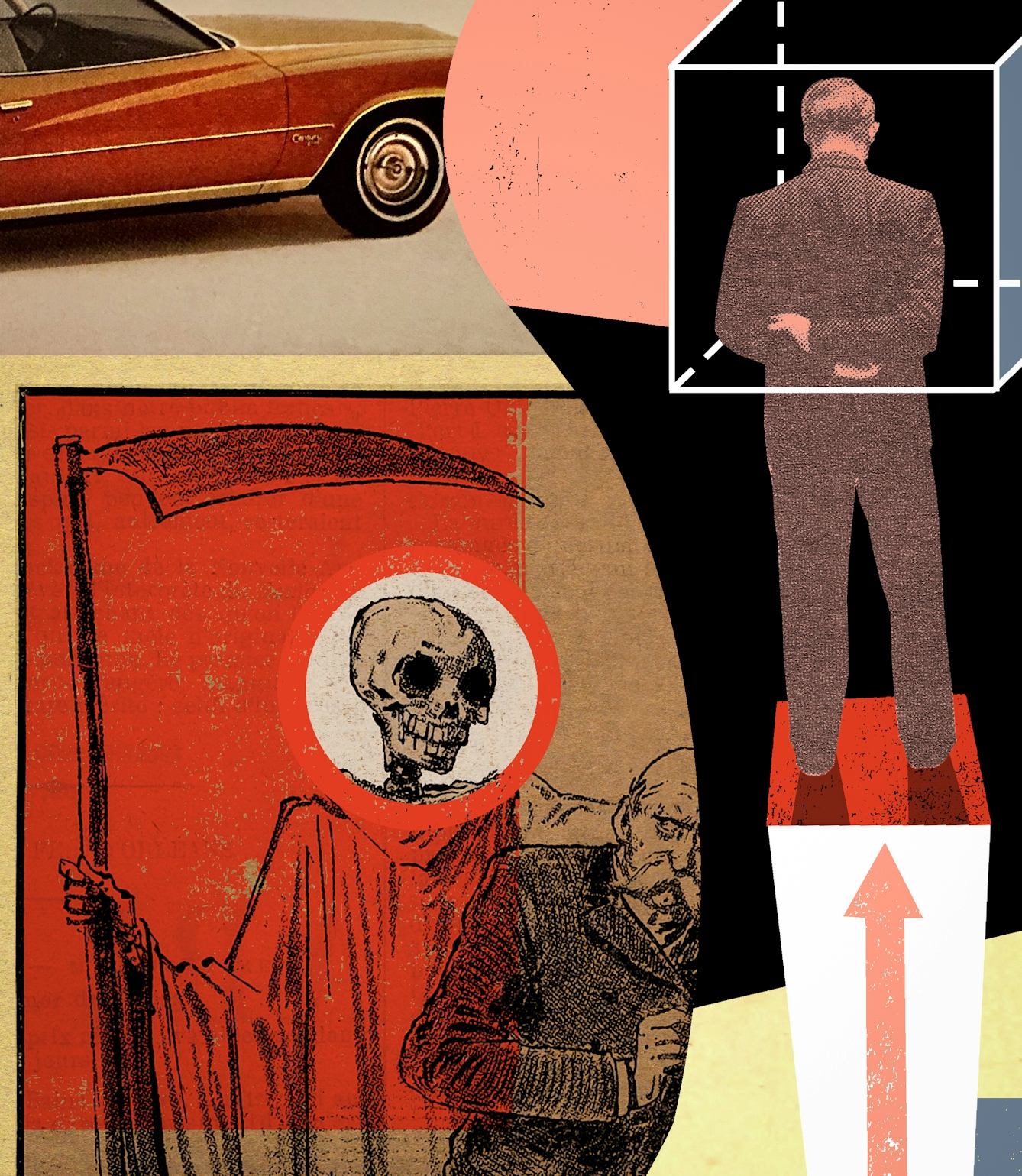

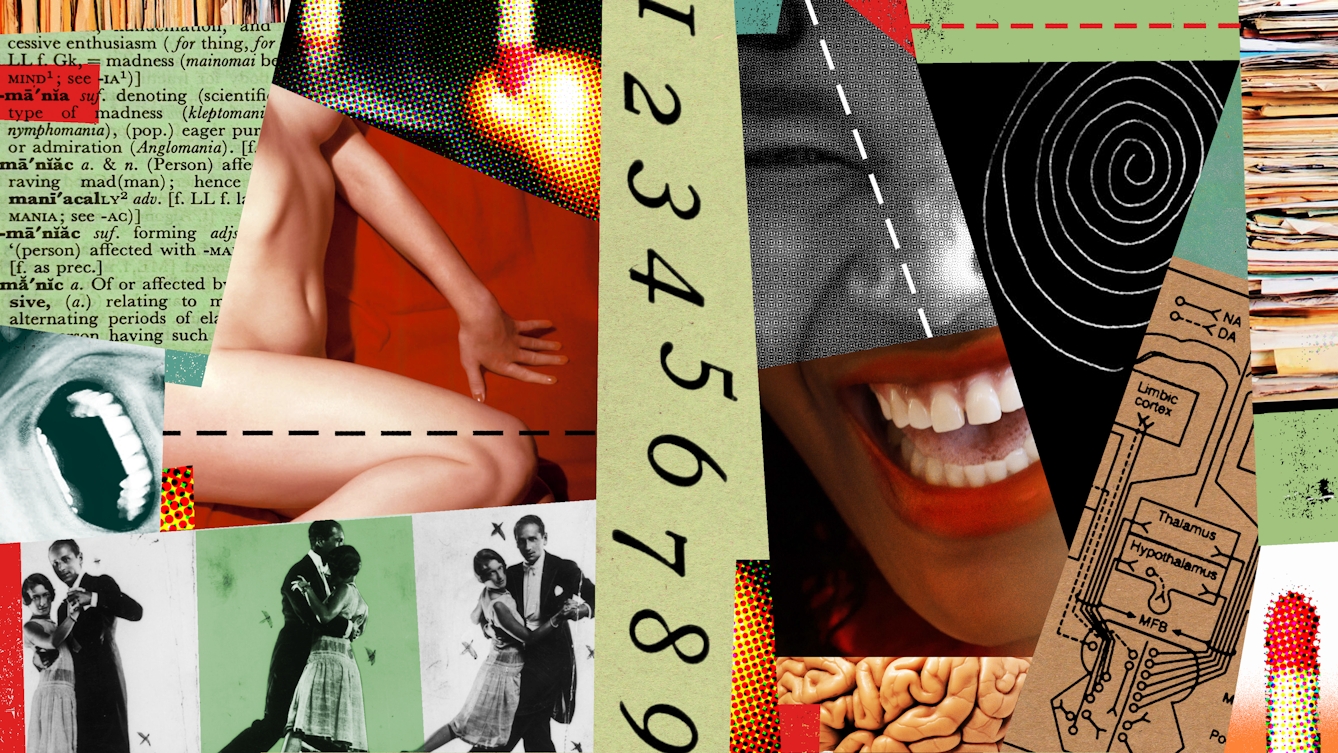

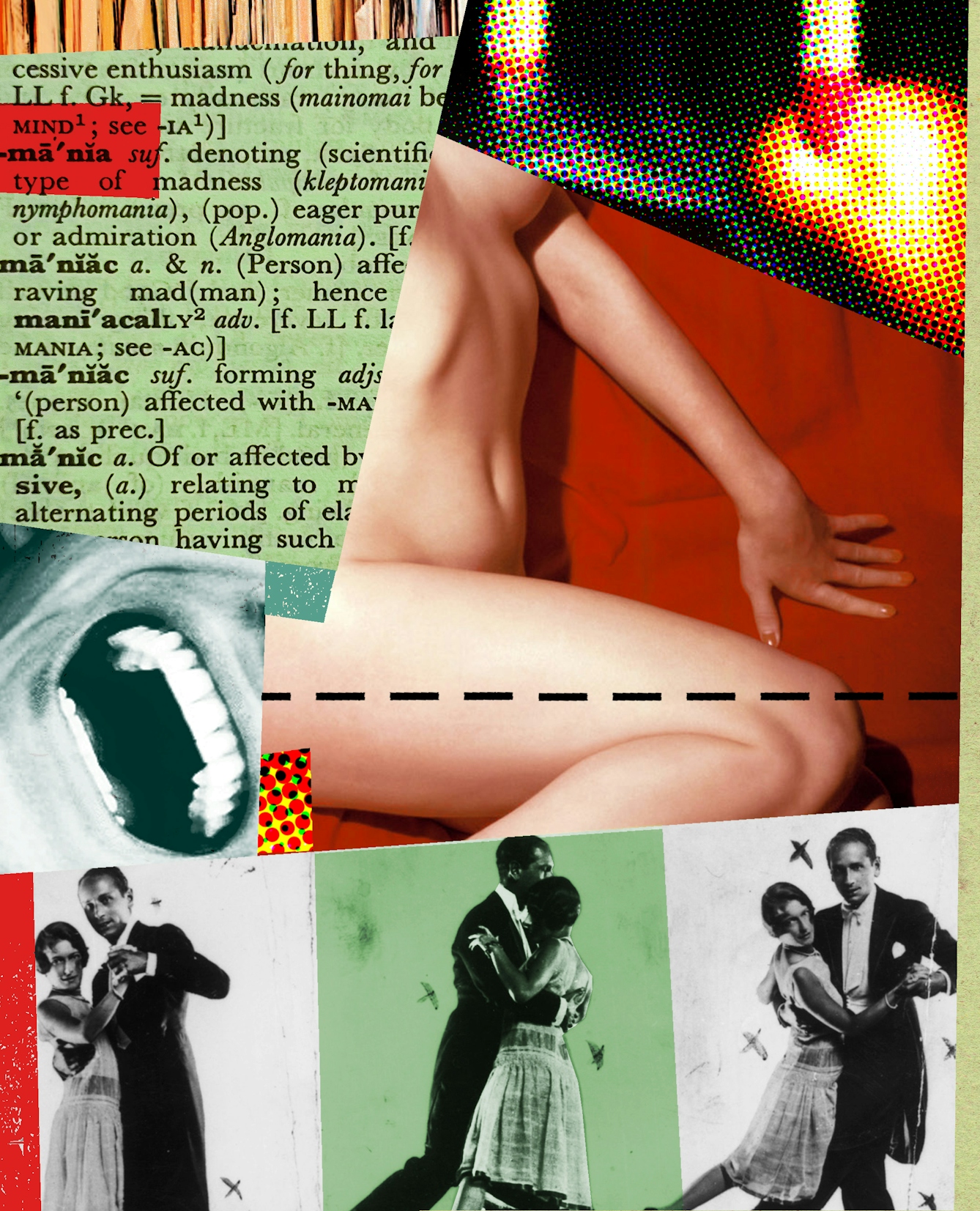

Words by Kate Summerscaleartwork by Tim Robinsonaverage reading time 9 minutes

- Book extract

We are all driven by our fears and desires, and sometimes we are in thrall to them. Benjamin Rush, a Founding Father of the United States, kicked off the craze for naming such fixations in 1786. Until then, the word ‘phobia’ (which is derived from Phobos, the Greek god of panic and terror) had been applied only to symptoms of physical disease, and the word ‘mania’ (from the Greek for ‘madness’) to social fashions. Rush recast both as psychological phenomena.

“I shall define phobia to be a fear of an imaginary evil,” he wrote, “or an undue fear of a real one.” He listed 18 phobias, among them terrors of dirt, ghosts, doctors and rats, and 26 new manias, including ‘gaming-mania’, ‘military-mania’ and ‘liberty-mania’.

Rush adopted a lightly comic tone – ‘home phobia’, he said, afflicted gentlemen who felt compelled to stop off at the tavern after work – but over the next century, psychiatrists developed a more complex understanding of these traits. They came to see phobias and manias as lurid traces of our evolutionary and personal histories, manifestations both of submerged animal instincts and of desires that we had repressed.

A string of manias was added to Rush’s list in the early part of the 19th century, and a great flurry of phobias and manias at the century’s close. The phobias included irrational fears of public spaces, small spaces, blushing and being buried alive (agoraphobia, claustrophobia, erythrophobia, taphephobia). The manias included compulsions to dance, to wander, to count and to pluck hair (choreomania, dromomania, arithmomania, trichotillomania).

And we have continued to discover new anxieties: nomophobia (a fear of being without a mobile phone), bambakomallophobia (a dread of cotton wool), coulrophobia (a horror of clowns), trypophobia (an aversion to clusters of holes). Many have been given more than one name – a fear of flying, for instance, is known as aerophobia, aviophobia, pteromerhanophobia and, more straightforwardly, flying phobia.

“The word ‘phobia’ had been applied only to symptoms of physical disease, and the word ‘mania’ to social fashions. In 1786 Benjamin Rush recast both as psychological phenomena.”

All phobias and manias are cultural creations: the moment at which each was identified – or invented – marked a change in how we thought about ourselves. A few are not psychiatric diagnoses at all, being words coined to name prejudice (homophobia, xenophobia), to mock fads or fashions (Beatlemania, tulipomania) or to make a joke (aibohphobia, hippopotomonstrosesquipediophobia, the supposed fears of palindromes and long words).

But most describe real and sometimes tormenting conditions. Phobias and manias reveal our inner landscapes – what we recoil from or lurch towards, what we can’t get out of our heads. Collectively, they are the most common anxiety disorders of our time.

“Phobia particularises anxiety,” observes the literary scholar David Trotter, “to the point at which it can be felt and known in its particularity, and thus counteracted or got around.” A mania, too, can condense a host of fears and desires. These private obsessions are the madnesses of the sane; perhaps the madnesses that keep us sane by crystallising our frights and fancies, and allowing us to proceed as if everything else makes sense.

Anxieties, aversions and full-blown phobias

To be diagnosed as a phobia, according to the American Psychiatric Association’s Diagnostic and Statistical Manual 5 (2013), a fear must be excessive, unreasonable and have lasted for six months or more; and it must have driven the individual to avoid the feared situation or object in a way that interferes with normal functioning.

The DSM-5 distinguishes social phobias, which are overwhelming fears of social situations, from specific phobias, which can be divided into five types: animal phobias; natural environment phobias (fears of heights, for instance, or of water); blood, injection and injury phobias; situational phobias (such as entrapment in closed spaces); and other extreme fears, such as a dread of vomiting, choking or noise.

“Phobias and manias reveal our inner landscapes – what we recoil from or lurch towards, what we can’t get out of our heads.”

Though specific phobias can be more responsive to treatment than any other anxious conditions, most people don’t report them, choosing instead to avoid the objects that they fear – it is thought that only one in eight people with such a phobia seeks help. This makes it difficult to measure their prevalence.

But a review in The Lancet Psychiatry in 2018, which synthesised 25 surveys carried out between 1984 and 2014, found that 7.2 per cent of us are likely to experience a specific phobia at some point in our lives. A survey carried out by the World Health Organization in 2017, using data from 22 countries, came to very similar conclusions.

These studies also indicated that specific phobias are much more common in children than adults, that the rates halve among the elderly, and that women are twice as phobic as men. This means that, on average, one woman in ten experiences a specific phobia, and one man in 20. National surveys suggest that a further 7 per cent of Americans and 12 per cent of Britons have social phobias.

These figures are for phobic disorders, which interfere with everyday life. Many more of us have milder aversions or dreads that we sometimes refer to as phobias: a strong dislike of public speaking or of visiting the dentist, of the sound of thunder, or the sight of spiders. In the US, more than 70 per cent of people say they have an unreasonable fear.

Phobias of specific objects, words or numbers can seem like ancient superstitions, vestiges of pagan beliefs.

“Many manias are obsessive behaviours, centred on an object, action or idea – hair-plucking, for example, or hoarding.”

When I began researching this subject, I did not think of myself as having any particular phobias – apart, perhaps, from my teenage dread of blushing and an enduring anxiety about flying – but by the time I’d finished I had talked myself into almost every one. Some terrors are no sooner imagined than felt.

The causes of these conditions are much disputed. Phobias of specific objects, words or numbers can seem like ancient superstitions, vestiges of pagan beliefs. The American psychologist Granville Stanley Hall, who catalogued 132 phobias in an essay of 1914, observed that some children developed an obsessive fear after having a fright. Shock, he wrote, was “a fertile mother of phobias”.

Sigmund Freud, who analysed phobic symptoms in two famous studies of 1909, proposed that a phobia was a suppressed fear displaced onto an external object: both an expression of anxiety and a defence against it. “Fleeing from an internal danger is a difficult enterprise,” he explained. “One can save oneself from an external danger by flight.”

Evolution or conditioning?

Evolutionary psychologists argue that many phobias are adaptive: our fears of heights and snakes are hardwired in our brains to prevent us from falling from heights or being bitten by snakes; our disgust at rats and slugs protects us from disease. Phobias of this kind may be part of our evolutionary inheritance, “biologically prepared” fears designed to shield us from external threats.

A phobic reaction does feel like an instinctive reflex. On detecting a threatening object or situation, our primitive brains release chemicals to help us fight or flee, and our physical responses – a shudder or a flinch, a wave of heat or nausea – seem to take us over.

“Along with the private urges, there are several communal manias, in which people have danced, giggled, trembled or screamed together.”

Evolution may help to explain why women are disproportionately phobic, especially in the years in which they are able to bear children: their heightened caution protects their offspring as well as themselves. But phobias may also seem more common in women because the social environment is more hostile to them – they have more reasons to be afraid – or because their fears are more often dismissed as irrational.

Evolutionary accounts of phobias are based on post hoc reasoning, and they don’t account for all phobias, nor why some individuals are phobic and others are not. In 1919 the American behavioural psychologists James Broadus Watson and Rosalie Rayner devised an experiment to show that a phobia could be induced by conditioning. In the 1960s, Albert Bandura demonstrated that a phobia could also be learnt by direct exposure to the anxieties and irrational fears of someone else, such as a parent.

Families pass on fear as much by example as by genes. Even if we are predisposed to certain anxieties, they need to be triggered by experience or education.

Acts of obsession and rebellion

If a phobia is a compulsion to avoid something, a mania is usually a compulsion to do something. The great French psychiatrist Jean-Étienne Esquirol invented the concept of monomania, or specific mania, early in the 19th century, while his countryman Pierre Janet wrote tender and attentive case studies of the men and women he treated for such conditions at the turn of the 20th century.

Many manias are obsessive behaviours, centred on an object, action or idea – hair-plucking, for example, or hoarding. Their prevalence is hard to assess, partly because modern medicine has subsumed many into categories such as addiction, obsessive-compulsive disorder, body-focused repetitive disorder, impulse-control disorder and borderline personality disorder.

“Manias often magnify ordinary desires – the wishes to laugh, light a fire, have sex, get high, surrender to misery, be adored.”

Like phobias, they are sometimes ascribed to chemical imbalances in the brain and sometimes to difficult or forbidden feelings. Often they magnify ordinary desires – the wishes to laugh, shout, buy things, steal things, tell a lie, light a fire, have sex, get high, pick at a scab, surrender to misery, be adored.

Along with the private urges, there are several communal manias, in which people have danced, giggled, trembled or screamed together. In the 1860s, for instance, a bout of demonomania seized the Alpine town of Morzine, and in the 1960s wild laughing broke out by a lake in Tanzania. These shared convulsions can seem like rebellions, in which unacknowledged feelings surge into view, and they can occasionally force us to reconsider what is rational.

When we decide that a particular behaviour is manic or phobic, we mark out our cultural as well as our psychological boundaries: we indicate the beliefs on which our social world is constructed. These borders shift over time, and in a moment of collective crisis – a war, a pandemic – they can change fast.

A phobia or a mania acts like a spell, endowing an object or an action with mysterious meaning and giving it the power to possess and transform us. These conditions may be oppressive, but they also enchant the world around us, making it as scary and vivid as a fairy tale. They exert a physical hold, like magic, and in doing so reveal our own strangeness.

‘The Book of Phobias and Manias’ is out now.

About the contributors

Kate Summerscale

Kate Summerscale is the author of the number-one bestselling ‘The Suspicions of Mr Whicher’, winner of the Samuel Johnson Prize for Non-Fiction 2008, winner of the Galaxy British Book of the Year Award, a Richard & Judy Book Club pick and adapted into a major ITV drama. Her debut, ‘The Queen of Whale Cay’, won a Somerset Maugham Award and was shortlisted for the Whitbread Biography Award. ‘The Wicked Boy’, published in 2016, won the Mystery Writers of America Edgar Award for Best Fact Crime. Her latest book, ‘The Haunting of Alma Fielding’, was shortlisted for the Baillie Gifford Prize for Non-Fiction. She lives in north London.

Tim Robinson

Tim Robinson is an illustrator and collage artist living in New York State’s Hudson Valley. Tim uses traditional elements along with digital imagery to produce editorial illustrations for clients such as the New York Times, The Nation, the Wall Street Journal, NPR, Condé Nast, the Boston Globe, and many, many more. Every collage is a glowing map that will lead readers deeper into the story.