Laura Grace Simpkins’s investigation into her medication gave her a good overview of lithium problems at different scales – local, national, global, even universal. It was time to act. But how would her doctor and psychiatrist react if she told them she wanted to come off lithium for environmental and social justice reasons? Was it possible to put something other than her own mental health first?

To stop or stay on lithium

Words and narration by Laura Grace Simpkinscomposition and sound design by Alice Boydphotography by Matjaž Krivicaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

Timothy Morton had warned ecognosis could be a downer. But I felt myself going up, up, up: it was like I had levitated through the atmosphere and was gazing down at the earth from the celestial plane. From my vantage in the heavens, I had a good overview of lithium problems on different levels – locally, nationally, globally, even universally.

Lithium was the third element synthesised in the Big Bang, yet there is markedly less of it in space than we’d expect, especially in comparison to the presence of other elements. There’s even a name for the universe’s mineral deficiency: the “cosmological lithium problem”.

Astronomers attempt to detect lithium in old stars using spectroscopy (a technique for measuring the colour of emitted light to ascertain chemical composition), as well as other imaging techniques using Very Large Telescopes. If present, lithium will give a reading of 700 nm; the wavelengths will appear “electric pink to crimson”. If I was a star, I thought, I’d be blindingly bright, a fever of fuchsia rays streaming from every pore; an incandescent, person-shaped disco ball.

What can I do about my lithium problem? I’d ruminate in starry bursts. What are my options? I guess I can stay on lithium or I can come off it. There isn’t an eco-friendly alternative. But lithium is not like plastic or air travel or avocados or anything else I could potentially give up. Lithium is the bitter pill I have to swallow. Don’t I?

‘Atrophy’, a sound art collaboration.

I wrote to the psychiatrist again: “If I or someone else with bipolar said to you, ‘I want to come off lithium for environmental reasons,’ what would you say?”

She replied: “I would ask the person to explain their thinking more fully. I would want to explore with them what they meant by ‘environmental reasons’, to check if they were rational and not delusional… My primary concern would be to absolutely ensure that the individual understood what the risks would be to them if they stopped lithium.”

It was an unusual question for me to ask. Of all the reasons why people choose to come off lithium, or never start it in the first place – adverse effects, fear of needles, popular misconceptions – environmental concerns rarely, if ever, feature. I couldn’t find one example documented in the medical literature.

I understood that, from the psychiatrist’s answer, my own rationality could be challenged by even raising the issue. I puzzled over how a medical professional could judge me rational or irrational, sane or insane, about something they said they’d never thought about, or been trained in.

’Til death do us part?

I decided to go and see my doctor. She was solid and taciturn, dressed in forget-me-not blue. I found myself wishing I could be as together as her. “I’d like to come off lithium…” I said. “Or try an alternative, maybe,” I added meekly, registering her worried expression and remembering she’d not replied to my email.

“Is this about the ‘socio-environmental reasons’?” she asked, warily. She’d clearly read it. Hearing my own phrasing repeated back to me was disquieting.

“Mostly,” I confessed. “But I’m also curious to see what happens off it.”

At this, she looked alarmed. “What do you mean exactly?” she said. “I’m not sure it’s a good idea to be experimenting with these things. Not after you’ve been doing so well the last few years. It’s also not a case of simply changing medications. If lithium is working for you, you should stick with it.”

“I’d like to be sure it’s the lithium making the difference,” I stated, “and not because I don’t drink any more, or something like that. If I come off it and need to go back on it, I will.”

“Do you think it’s not working?”

“That’s not what I’m saying,” I said. “I’ve been doing some research. It’s made me recognise my mental health shouldn’t come before everything and everyone else on this planet. Just because I ‘am bipolar’ does not mean I am the centre of the universe, and I need to stop being so solipsistic. I should at least know for sure whether or not it’s imperative I stay on lithium.”

My mental health shouldn’t come before everything and everyone else on this planet.

She stared at me like I was completely deranged. I knew I’d never been saner.

“If you’re sure.” The doctor exhaled slowly, her eyebrows raised and lips puckered. “I will get some advice from your mental health team. A psychiatrist would have to sign off on it.”

I nodded.

“I’ll try and call you with any updates later in the week.”

I left the doctor’s and walked down the hill home. When I got back, I wondered how many people after receiving a diagnosis of bipolar disorder had it reviewed or revoked. That piece of letter-headed paper with the diagnosis printed on it growing dusty in a box somewhere was more of a cheap marriage certificate than I’d bargained for.

Was I wedded to my diagnosis for life? Would it be lithium and I ’til death do us part?

A few days later, I heard from my doctor. “The psychiatrist has said you can reduce your lithium if you still want to. She suggested we gradually taper it off over the course of six months and see what happens.”

I went quiet. The option was being offered to me and I was vacillating. I swallowed.

“Take as long as you need to think about it,” said my doctor. “No rush.”

Lithium is the bitter pill I have to swallow. Don’t I?

I ended the call. I hadn’t expected the decision to come so quickly. I was thrown. I’d expected to be given more guidance. It seemed like everything was up to me. Doubts flickered across my mind. What did I know? I thought. Was it sane or insane, rational or irrational, to come off a medication for socio-environmental reasons?

Lithium and I had been together for four years. It had been like a marriage. Lithified, two had become one. I realised what I wanted, more than anything, wasn’t an immediate divorce, but couples counselling, a sensible, grown-up conversation about our struggles. But the choice I had was lithium or no lithium. I was caught between a rock and a hard place.

About the contributors

Laura Grace Simpkins

Laura Grace Simpkins writes and performs about herself, madness and death. Her writing has been published by the Guardian, New Scientist and the British Medical Journal’s Medical Humanities, as well as broadcast on BBC Radio. She is currently working on her first book.

Alice Boyd

Alice Boyd is a London and Bristol-based composer and sound artist. Her work uses the voice, everyday sounds and electronic textures to tell stories about the world around us. She has been selected as one of Sound and Music’s New Voices composers 2020, and has worked with venues such as Eden Project and Donmar Warehouse.

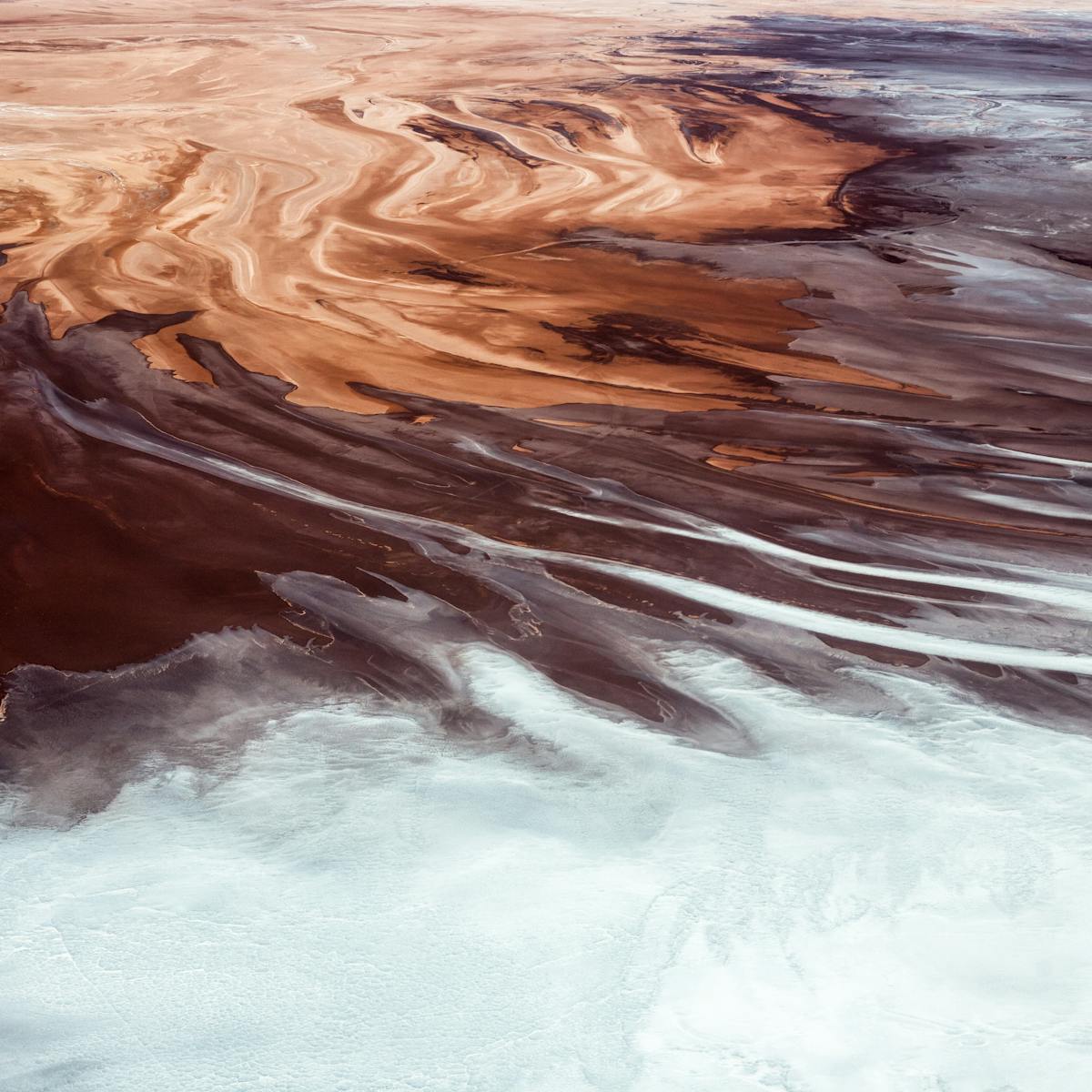

Matjaž Krivic

Matjaž Krivic is a documentary photographer capturing stories of people and places, primarily focusing on environmental issues. For over 25 years he has covered the face of the earth in his intense, personal and aesthetically moving style that has won him several prestigious awards. The past six years he has been immersed in the visual documentation of the lithium industry and also how companies and even countries are essentially washing away the climate sins of the past to create a greener and sustainable future.