While the concept of other worlds is hundreds of years old, the new popularity of science fiction in the early 20th century brought predatory alien invaders to the forefront of people’s imaginations. A century later, fiction still has a tendency to characterise the greatest threat to our existence – climate change – as some form of extraterrestrial judgement.

The Martians are coming

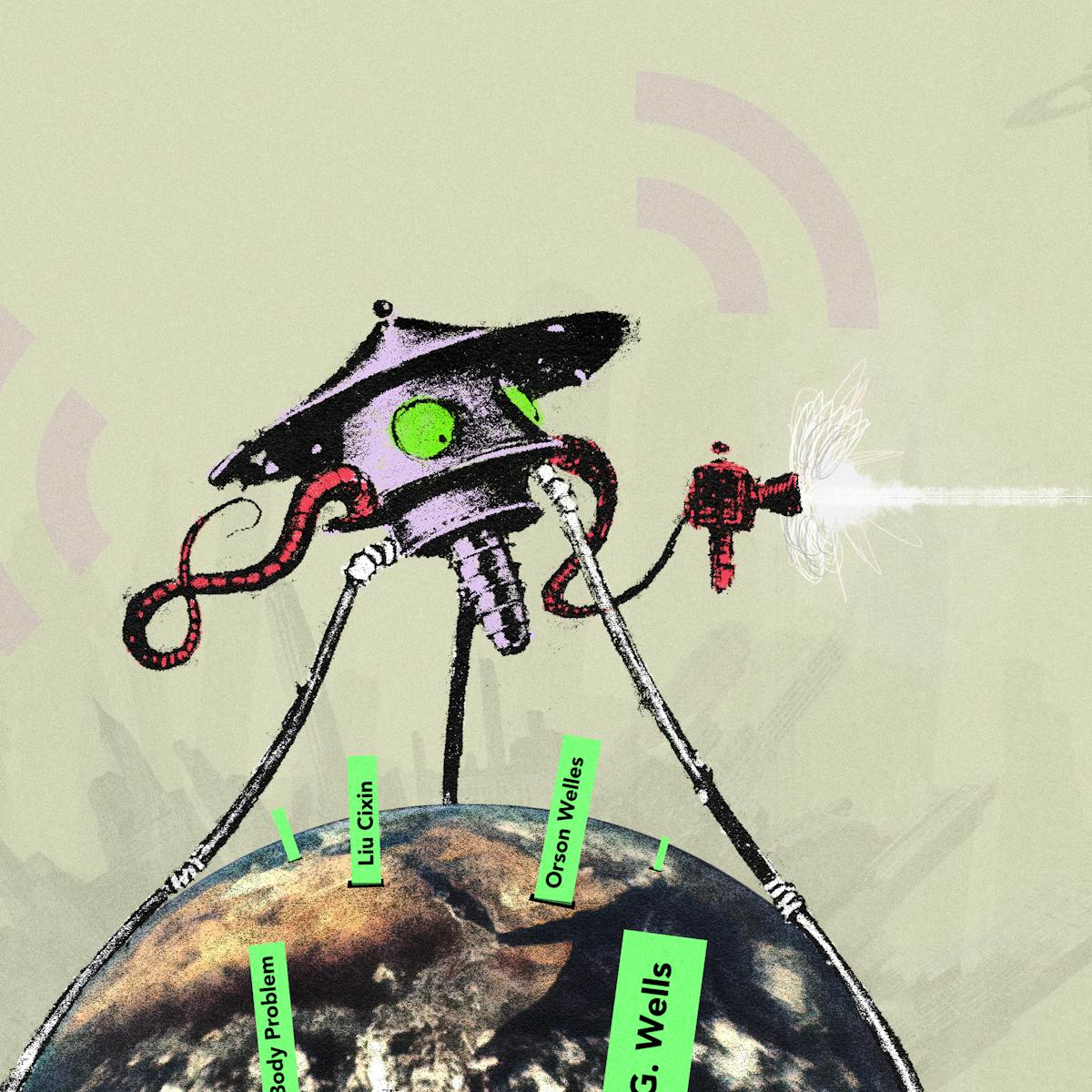

Words by Charlotte Sleighartwork by Gergo Vargaaverage reading time 5 minutes

- Serial

In 1938, a musical radio broadcast was repeatedly interrupted by news flashes concerning ominous phenomena observed in the sky. These news flashes soon gave way to “live broadcasts” by reporters describing their encounters with beings whose landing was, evidently, the cause of the lights in the sky. Their words disappeared into radio silence as they were sizzled up by heat rays wielded by the arrivals.

This alarming broadcast was, famously, all a radio play, adapted by Orson Welles from ‘The War of the Worlds’, an 1898 novel about Martian invasion by his near namesake, H G Wells.

Not everyone has been as alarmed as Welles’s listeners by the prospect of alien life. Many organised and traditional religions make space for celestial beings, or for entire worlds peopled by unearthly forms of life. Medieval Muslim scholars found their reverence for Allah enhanced by the thought that he had made “thousands and thousands of worlds, and thousands and thousands of humankind”.

Modern science brought a fresh ambivalence to this traditional perspective, however. On the one hand, wielding a telescope and mathematics gave humans a tremendous sense of power – they could reach right across the cosmos to observe and understand heavenly bodies. On the other, living in a universe that was no longer centred on their own sun, and filled with other solar systems, brought with it a disconcerting sense of insignificance.

How to deal with this tension?

Psychology and space

Megalomaniacs and crazy scientists are often described as having an ego the size of a planet, but in Freudian terms it is the super-ego that is the size (and shape) of a planet. The super-ego is, for Freud, the internal law enforcer that prevents us from following our crudest desires. It is not an inner Jedi, however, but an inner Sith; it is the force of aggression turned upon itself, warped into the self-punishment of guilt and judgement.

“In recent years, critics have read Wells’s original alien novel as exploring a sort of cosmic punishment: a guilty payback for what was deserved.”

With the Christian God largely out of the picture by the late 20th century in Britain, people projected their super-ego fears about punishment and obliteration onto the physical ‘heavens’. Death comes from the skies; it’s not so far from imagery of Christ’s second coming, with judgement and vengeance upon the wicked. Other planets, and alien races, are the perfect embodiment of these feelings. By imagining this enemy without, we avoid having to think too much about our own failings, which reside as the enemy within.

In recent years, critics have read Wells’s original alien novel as exploring a sort of cosmic punishment: a guilty payback for what was deserved. For Wells and his late-Victorian readers, the sins inviting extraterrestrial judgement were colonisation and violence. “The Tasmanians,” wrote Wells, “in spite of their human likeness, were entirely swept out of existence in a war of extermination waged by European immigrants, in the space of fifty years.”

‘The War of the Worlds’ asks what would happen if the tables were turned and white Britons were treated by aliens as they had treated the original inhabitants of Tasmania: “Are we such apostles of mercy as to complain if the Martians warred in the same spirit?”

Insect aliens and the end of the world

Wells’s aliens – and those of his science-fiction successors – often look like insects. Insects were opponents of European colonists in their brutal fantasies of ruling the world. They spread disease; they destroyed food and buildings. They lurked in crevices and surged in unexpected swarms; they could not be contained by conventional weapons intended for humans.

They were, in short, the means by which the empire struck back. In more recent years, perhaps, they stand as moral representatives of an ecosphere destroyed by chemical vandalism.

In Liu Cixin’s magnificent novel ‘The Three-Body Problem’ (2006), the astrophysicist Ye Wenjie also deliberately courts alien invasion as a means of judgement. Disillusioned and disgusted by both personal and public life, she invites the Trisolaran race to earth in the full knowledge that they are likely to destroy humanity. Her billionaire ally purchases a ship to use as a base for their traitorous activities: apocalyptically enough, it is called ‘Judgement Day’. Ye’s invitation is a bid to have the Trisolarans play the role of God and resolve humanity’s fate one way or the other.

“Wells’s aliens often look like insects. Insects were opponents of European colonists in their brutal fantasies of ruling the world. They spread disease; they destroyed food and buildings.”

The recent parody of climate-change politics, ‘Don’t Look Up’ (2022), makes another extraterrestrial judgement – this time an asteroid – into an analogy for climate change. In the film, politicians scramble to downplay the threat of the earth-bound rock, despite scientists’ warnings of certain and total annihilation.

There is a problem with the analogy of violent death from outer space and climate change, though. It makes climate change into a deus ex machina – a random threat to humanity from outside our ordinary lives. It is as though carbon dioxide were heat rays released by aliens, rather than something pumped out by the cattle we farm, the cars we drive, the factories that make our fast fashion.

Scriptures of science

Climate change is not, as children are taught in their science classes, a problem about carbon dioxide. It is a problem about certain humans and their production of carbon dioxide. When we humanise the diagnosis of the problem in this way, we shift the way to talk about the response.

The response is not to do something about carbon dioxide, but to do something about human behaviour. It is a subtle but powerfully different way of thinking about the problem.

A focus on alien attack makes science fiction into the scripture of science – and not in a good way. It perpetuates a childish belief that there is a fickle and vengeful god who will impose punishment from the heavens. By externalising the process of judgement, it prevents humans from thinking about the consequences of their own actions and owning their capacity to make change.

Scarier than Martians with heat guns is the notion that there are no Martians coming, either to destroy or to save us.

About the contributors

Charlotte Sleigh

Charlotte Sleigh is an interdisciplinary writer and practitioner in the science humanities. Her most recent book is ‘Human’ (Reaktion, 2020). She is Honorary Professor at the Department of Science and Technology Studies, UCL, and current president of the British Society for the History of Science.

Gergo Varga

Gergo Varga is an illustrator, collage animator, motion designer and the name behind ‘varrgo’. varrgo is a place where Gergo creates and animates mixed-media projects, particularly in the style of collages and cut-outs. He enjoys working with things that have already had a life, from old magazines to scribbles in a notebook. His longest-running creative project is ‘oners’, where he visualises one-minute quotes from contemporary thinkers. Gergo created the animations and illustrations for ‘Apocalypse How?’ and ‘Eugenics and Other Stories’, published on Wellcome Collection Stories.