On holidays without their husbands, a group of sisters paraded in fine, fashionable, handmade clothes on seafronts and in cafés, attracting the admiring gaze of local men and the suspicion of their wives. At the heart of their sartorial success was Joan, whose skilled tailoring was the secret behind the sisters’ mysterious allure.

Our mothers only travelled abroad to places where they could pass for locals. And, on arriving, their sole business became making the village men and women wonder how the hell they’d missed these gems. Unable to speak the language, our mothers – some girdled, some pert – suspected they were wanted before they arrived, and that really showed in what they wore.

We children were too young for husbands, but for a few weeks each year, without our fathers, we imitated our single mothers – some neat at the ankle, some not so. With mimicked aplomb, we smudged between the cast-iron backs of chairs and café tables, becoming surefooted enough never to snag on the thorny men planted at them. When, in the afternoon, families rolled together on mats in the shade, we young ones cut flat figures against a sky, walking on the very edge of swimming pools with our wings spread.

The binds that breed creativity

Joan had more time than her sisters to dream about what might be beautiful and to whom. As the child-free sister and a seamstress, her almost complete lack of schooling made room for a heightened sense of colour and form. This reached its most sensitive attunement when making everyone’s holiday clothes.

It was from tailoring that she learned what passing for locals meant. Stretching and sensing the fashions outside her greasy rag-trade environs, she installed a machine in her back bedroom, cutting out on the floor. She unleashed a mindless daring to take hold of the scissors and cut the pattern to make clothes that would be both indistinguishable from local attire and noteworthy.

It was a gift she had, perhaps because of months of hospitalisation, where her affected leg would be lagged in wet plaster bandages. Or it would be rubbed by her mother with neatsfoot oil, a fat rendered from cattle shins that stank to the heavens but made saddles supple.

Passing for locals meant wearing their most saintly jewellery every day: a double-sided relievo miraculous medal for Mary; a classical bead-and-link bracelet bought for Rita in Italy, trusted to Iris (gold ring with turquoise) on dry land.

Rita was the aunty who, when she deigned to tell a story, could keep you by her side for the whole day. And whose children were in no doubt that she could swim further and faster than them. Joan’s charm bracelet jangled, catching the ear of passing children, who were only allowed to open the robust clam with the pearl. Rita would bask in the last sun while Joan laid out our evening outfits with a little Caramello sweetie under each. We were allowed to touch whichever charms took our fancy.

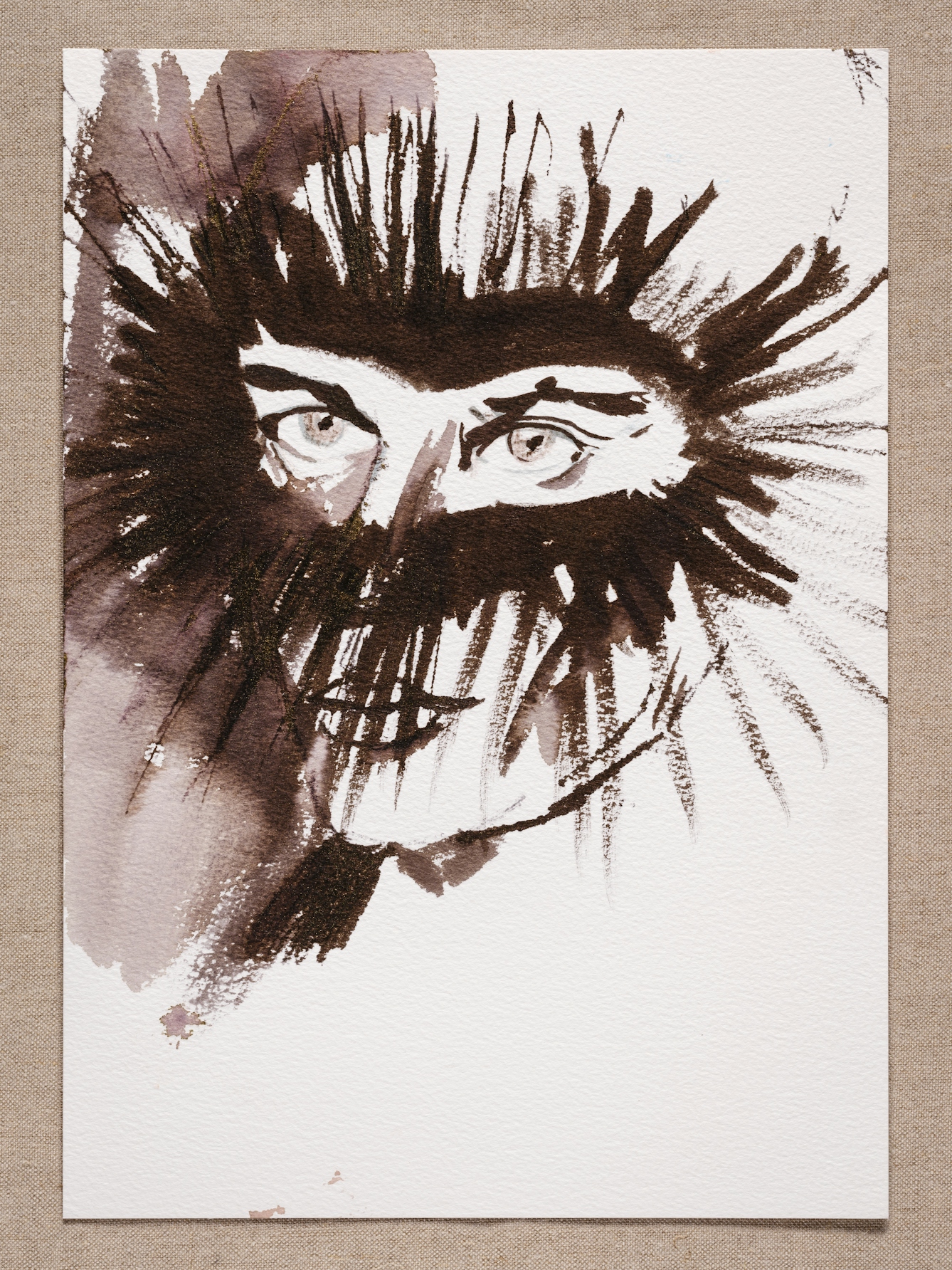

Joan returning a stare from Yul Brynner in a Cádiz market.

A brush with fame

Being the aunty with polio, Joan had to be more doggedly stylish than the others. I see her now in her terry-towelling smock and matching hat with a wide, soft brim which, by virtue of heat, salt and invisible facings, achieved professional floppiness.

Because of her marked limp she was sweatier than her sisters, but insisted upon not being waited for, leaning on the youngest cousin as her human crutch. We older ones had served our indenture. We had suffered that spraining back of the wrist needed for Joan to gain purchase and lurch eagerly forward, one leg of her tan clam-diggers shamelessly squared out by the struts of her calliper.

A blaze of tangerine and russet crescents scything across terrycloth, Joan passed the café of men. From their hooded looks it seemed they dreamed of her just as much as they did the dark-skinned sisters, who Joan was used to being nimbler. Joan was focused instead on their kitten heels in front.

She indulged herself in the thought of a precious interlude only a year before, where she had found herself being stared at by Yul Brynner at a shoe stall.

They had been at a street market in Cádiz when he appeared at her shoulder, asking intently if she was “going to buy them”. One shoe in hand, she looked around her first for confirmation that it was indeed him; some acknowledgement from half the world that had seen him in ‘The King and I’.

Between his familiarity and his fame, she was pincered and, thus squeezed, she wondered whether he was implying she was going to steal that shoe. His glittering black eyes implied it. Indignant, she stared back, setting her smile to float in the blended haze of her heavy tinted creams with the German names.

He could not tell from her appearance that through one heel of every pair of shoes she’d ever owned, she used a hot steel rod to gouge into the plastic. Or that she regularly forced her way through rubber until it furled from tubular cavities she created: anything so that she could attach her iron’s pronged stirrup. Cuban, stacked – shoe heels that, she told herself, weren’t so different from those her sisters wore on holiday.

Joan and Mary, postcard shopping.

She turned from him and set the wedge heel free – a tubby little cork tug – into the sea of other shoes for sale. She was barely able to wait to tell her sisters how Yul had mentioned her jet-black curls, noticed the freckled skin at the sweetheart neck, the bias of the skirt, the hand-sewn tucks. Perhaps he too had sensed she was no one’s mother, perhaps he too had caught the trace of tea in her sweat.

But this year, the locals had smelled our foreign mothers on the wind and had let each other know, by some white-milked root system no doubt, what was coming. Not fool enough to be caught, they moaned with their mouths closed. With their women shut in shade, the men stayed in the beach-road café well into the afternoon, tapping the tabletop as our mothers tilted by in sensual heels, laden with heavy bags of uneaten fruit.

In front of the men, they sometimes took a break to smoke. Lathered and garlanded with wet towels, they watched for us arriving with the tip of our lilo dragging, scoring the dust road. It cramped our palms, our short red arms not adequate to the width of the sad, warm pet it had become. We dropped it gladly, and noted the men’s darting looks tacking together whose kids might be whose.

Stepping out at night

The scent of evening brought out the two friendliest sisters first, throbbing under thin neon belts and pressing their curves against perfectly flat zips snugly installed in the small of the back.

Joan surveyed her creations; handmade and strapless meant nothing was left to chance, banding secured tight above enviable breasts. We skipped between our kin, admiring and stroking their silky bodies as they strolled towards the town in static prints alive with either ovals or clusters of triangles. I wore my navy-striped pinafore sewn with a patch of two cherries at the breast; a detail that had inspired such terror in me at the bullfight.

The dark-skinned pair went ahead toward the harbour, neatly promenading with dainty-heeled steps, and the local women steamed at the way these foreigners with their matching bags and hats had the menfolk puzzled right to their centres.

Wives stayed together in solidarity around fires on the beach, casting seed shells into flames. The smoke curled to show forked tongues flicking over facings and around tightly sewn buttons, the base of the split straining at a button’s taut cotton roots. The sisters passed, leaving plumes of carelessness.

The kids, with curious grey teeth, stepped on each others’ toes. Cigarettes were knocked from hands, but Joan didn’t rush. The gap between Joan and the sisters widened. Ice creams melted. After all, she knew that they needed her for the hand-sewn ruffles, the things that meant her frocks wanted watching. They’d wait for her.

About the contributors

Rachel Genn

Rachel Genn is a senior lecturer at Manchester Writing School and the University of Sheffield. Formerly a neuroscientist, she was a Royal Society Fellow at the University of British Columbia, Canada, and has written two novels: ‘The Cure’ (2011), and ‘What You Could Have Won’ (2020). She was a Leverhulme Artist-in-Residence at the University of Sheffield (2016) and has non-fiction in Granta, the Los Angeles Review of Books, Aeon, and the New Statesman. She is currently working on a collection of non-fiction about her family’s injuries, fighting and addiction to regret.

Sally Anne Wickenden

Sally Anne Wickenden is an international artist and illustrator from Sheffield, England. Her work inhabits the dreamy, liminal spaces somewhere between the familiar and the otherworldly, with human and personal connections as deep as they flow.