A high pollen count can ruin spring, summer and beyond, with climate change and air pollution only making things worse. A lifelong hay-fever sufferer, David Jesudason reflects on why he might have been fated to have a pollen allergy, and talks to two experts about causes, treatments and cures.

My classmates were laughing. The teachers were bemused. My mother was angry.

I vividly remember the day I had to be taken home from school because of hay fever. My eyes were so sore and my vision so blurry that I needed help walking. I was five years old.

Forty years later, hay fever continues to blight my life. It ruins springs, summers and even autumn – last year, autumn was unusually warm, humid and windy. It’s made me avoid parks, fields and sometimes holidays, despite loving the outdoors and camping particularly.

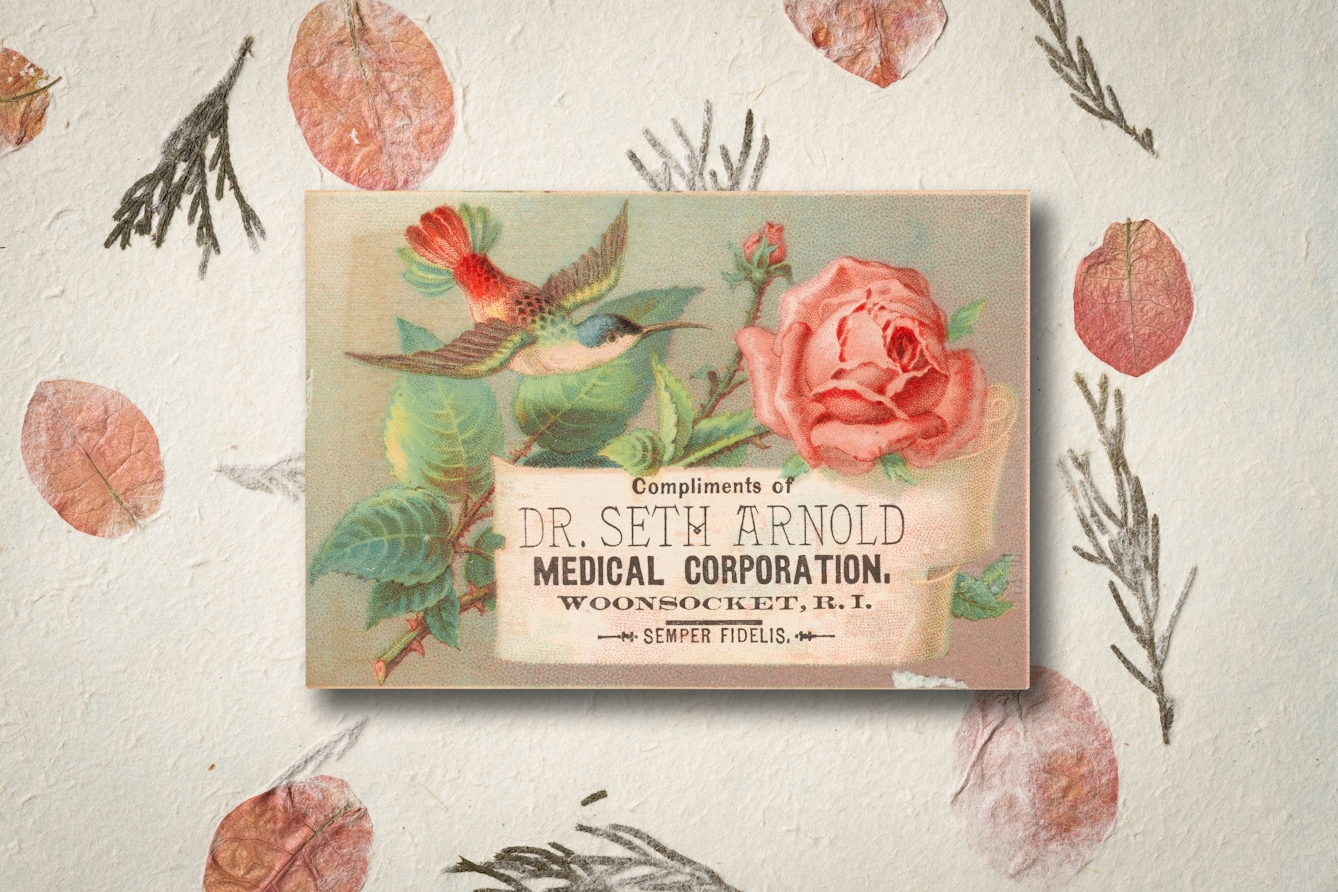

Hay fever is an allergic reaction to pollen, resulting in cold-like symptoms, including sneezing, coughing, a running or blocked nose, and itchy eyes. It was first recorded in 1564 by Italian anatomist Leonardo Botallo, who called it “summer catarrh” and described it as an aversion to roses.

Over 200 years later, in 1819, Liverpool doctor John Bostock was the first to describe the symptoms in detail – symptoms he’d suffered every June and July since he was a child. In 1829, a surgeon called William Gordon outlined his ‘Observations on the Nature, Cause and Treatment of Hay-Asthma’ in the London Medical Gazette.

Back then, pollen allergies were rare, but they have become much more common. One horticulturist blames botanical sexism, while other people cite climate change or modern hygiene.

When I was at university, my male friends saw hay fever as a sign of weakness – “He’s such a wimp,” I overheard one say. I would drink to excess to null the pain, which made the symptoms worse and the hangovers like flu. At Glastonbury one year I was even told, “It’s all in your head, man,” by a fellow festival-goer, who saw my sneezing and running eyes as Oscar-winning acting.

“Hay fever continues to blight my life. It ruins springs, summers and even autumn.”

“I always tell people it’s more than a nasal condition,” says Michael Blaiss, Executive Medical Director at the American College of Allergy, Asthma and Immunology. “It really affects the whole patient and it needs to be aggressively managed to control the condition.

“[Views] that conditions like hay fever are psychosomatic were always out there, but this got worse with Covid denial. You hear theories that it’s plots by physicians or drug companies to make money. It’s simply not true: we have the science and we have the data.”

To make matters worse for sufferers – there are thought to be almost ten million of us in England – the hay-fever ‘seasons’ are getting longer as climate change leads to prolonged summery spells, earlier springs and later winters. (Although, confusingly, at the height of 2022’s record-breaking heatwave I had fewer symptoms because the grass was scorched and plants died.)

“Every year pollen levels are different,” Blaiss says. “And that becomes a problem when we’re doing clinical studies. One of the things we do know is it’s getting worse and that’s to do with climate change. Increased levels of CO2 on plants, increased pollination, pollination is sooner, the seasons are longer, the pollen levels are higher and the antigenicity of the pollen – in other words, how it will trigger an allergic reaction – is more.”

The lowdown on symptom control

I tell Blaiss about my early childhood and he says it reads like a ticked checklist for someone who was fated to suffer badly with hay fever and rhinitis. Children, he explains, who socialise little before starting school and who aren’t exposed to animals are much more likely to develop allergies. A predisposition to hay fever can also be inherited, while living in a polluted area exacerbates the problem. We had no pets (tick), I didn’t go to nursery or preschool (tick), my mum had hay fever (tick), and we lived by a main road (tick).

A predisposition to hay fever can be inherited, while living in a polluted area exacerbates the problem.

As I got older, I became wary of doctors and tried to medicate the condition myself. Growing up in a mono-cultured market town in Bedfordshire, I often found myself being patronised or sometimes mocked by health workers. Even now I try to avoid seeing a GP unless I really need to. The people I interviewed for this piece were taken aback by the lack of interaction I’ve had with medical professionals.

“There are a lot of things we can do to control the condition and, in some cases, cure it,” explains Blaiss.

He sees a potential cure as quite extreme because over-the-counter medicines, such as intranasal steroid sprays, can be effective when taken throughout the hay-fever season, especially when started early in the spring. He then describes using over-the-counter antihistamines as “rescue medicine”.

“As I got older, I became wary of doctors and tried to medicate the condition myself.”

To understand how a cure may be possible, we have to go back more than 110 years and examine the work of pathologist Leonard Noon and his colleague John Freeman. In 1911, Noon published an article in the Lancet describing the development of a hay-fever desensitisation treatment, which involved injecting patients with extracts of pollen. Noon removed microscopic pollen grains using alcohol and administered them to his subjects, upping the dose over time.

“The injection treatment still hasn’t changed much in 100 years,” says Stephen Durham, Professor of Allergy and Respiratory Medicine at Royal Brompton Hospital, London. “We still purify natural grass pollen, we extract the major protein compound by ethanol, which is then standardised and injected under the skin.”

The way the patient is inoculated has moved on a bit, though. Durham confirms he can now also administer a tablet which dissolves under the tongue, and is available for grass and tree pollen and for house dust mites. He believes I’m probably allergic to the latter, as I have perennial problems with sneezing and itchy eyes.

This type of immunotherapy is said to yield amazing results, but it’s reserved for cases where prescribed medicines have failed. I tell Durham that I often try nasal sprays and antihistamines but give up when symptoms don’t improve or when the weather changes.

He explains that supermarket-bought treatments don’t tend to last long enough, whereas with a proper prescription you get “a decent month’s supply”. He thinks patients often don’t realise how long they need to take hay-fever medicine for, but that pharmacists are becoming more aware about how to treat it.

I’m now trying Chinese medicine, including acupuncture. Durham says he has a number of patients that find treatments like it helpful, but warns of the placebo effect and how there’s never been any effective “double blind” tests to prove effectiveness. “I wouldn't discourage them if they found benefits, but I wouldn’t recommend it,” he says.

After my conversations with Blaiss and Durham, I felt like I’d been listened to for the first time about hay fever and the impact it has on my life. It was always something I’d suffered silently with in a darkened room, while I heard voices outside enjoying the sun. Now it’s time to realise that it’s not just me who struggles to get through the summer, and that help is there if I’m willing to take it.

About the contributors

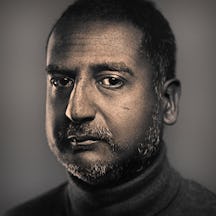

David Jesudason

David Jesudason is a freelance journalist who covers race issues for BBC Culture, Pellicle and Vittles. He was named Beer Writer of the Year in 2023, after his first book ‘Desi Pubs, A Guide to British-Indian Pubs, Food and Culture’ was hailed as “the most important volume on pubs in 50 years”. David also writes ‘Pub Episodes of My Life’, a weekly newsletter about the drinking establishments that serve marginalised people.

Steven Pocock

Steven is a photographer at Wellcome. His photography takes inspiration from the museum’s rich and varied collections. He enjoys collaborating on creative projects and taking them to imaginative places.