Over sixty years have passed since thalidomide was first prescribed to pregnant women as a 'safe' treatment for ailments associated with pregnancy. Now you can hear from some of the women who took the drug about the fear, isolation and grief they experienced as the full impact of the thalidomide scandal gradually unfolded around them.

Thalidomide, a bitter pill

Words by Ruth Blueartwork by Hollie Chastainaverage reading time 6 minutes

- Serial

During a short, intense period in the late 1950s and early 1960s, thousands of lives were changed for ever because of a pharmaceutical compound called thalidomide. The impact was felt not only by those directly affected and their families, but also by wider society, undermining trust in pharmaceutical companies, doctors and the medical justice system for decades to come.

Since the 1960s, the story of thalidomide has been written about widely, highlighting inadequate medical testing, unethical marketing and promotion, and a callous indifference from the pharmaceutical industry, the medical establishment and the state. But we rarely hear directly from the mothers who were given the drug or from the babies, now adults, who survived and continue to live with the physical and mental damage it wrought.

Over the past few years, the UK Thalidomide Society has been capturing the personal stories of thalidomide-affected families in the form of recorded interviews. The recordings allow people, from all backgrounds and locations in the UK, who were affected by thalidomide to tell their stories in their own words.

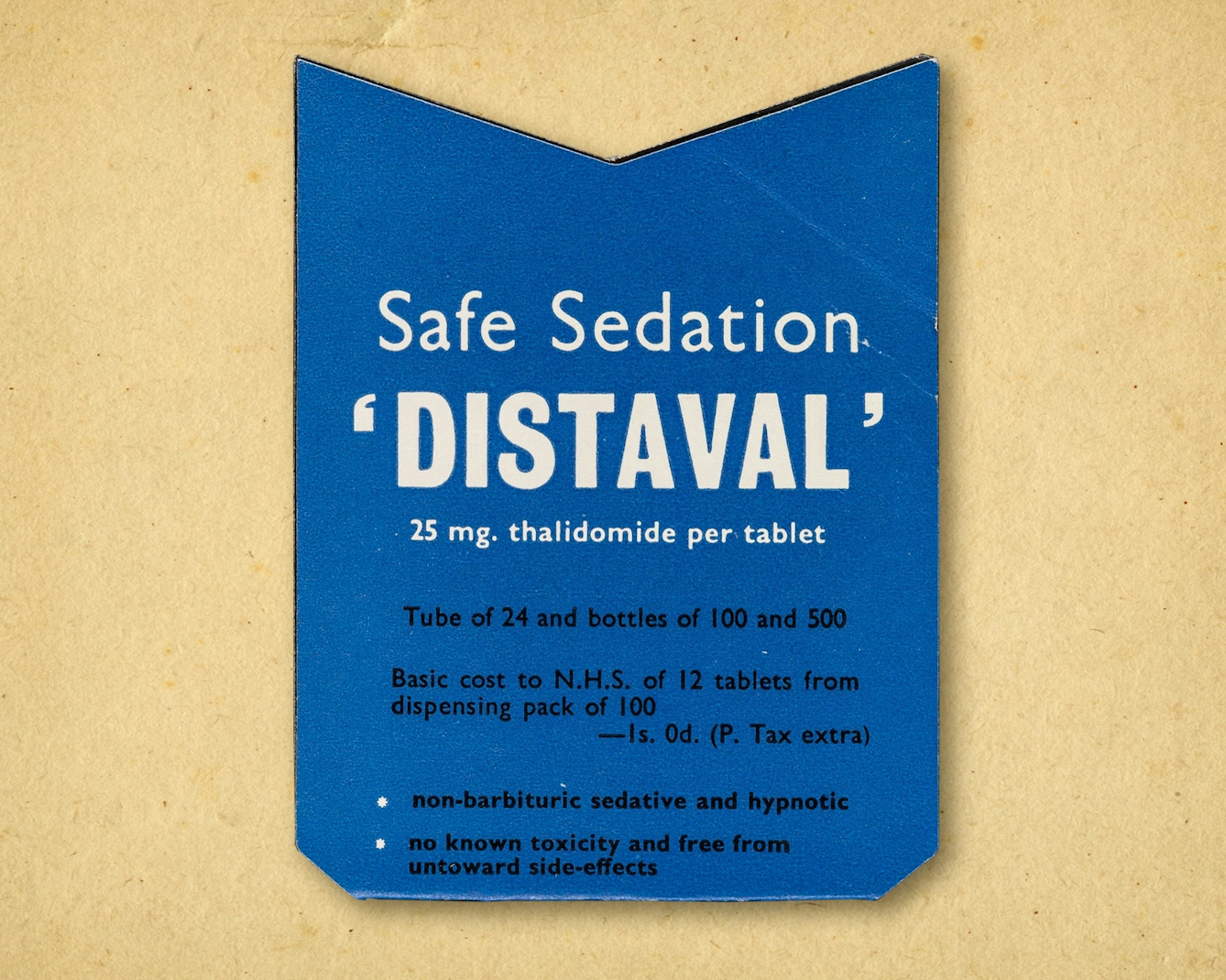

Die-cut advertisement issued by the Distillers Company (Biochemicals) Limited for the sedatives Distaval and Distaval Forte, c.1958.

A ‘safe’ sedative

The pharmaceutical compound thalidomide was created by Chemie Grünenthal, a West German pharmaceutical company. It was first officially released in 1957 in Germany for use as a non-addictive sedative which it was impossible to overdose on.

Although developed as a sedative or tranquilliser, thalidomide was soon prescribed for a wide range of minor conditions. Despite very limited clinical trials on humans and none on pregnant women, the drug was marketed as suitable for treating morning sickness, anxiety and insomnia during early pregnancy.

By the time it was officially confirmed that thalidomide could pass through the uterine wall and interfere with the development of the foetus, thousands of pregnant women had been given the drug. In fact, the first thalidomide-affected baby had been born in 1956 to a Grünenthal employee.

There were around 147,000 thalidomide-affected pregnancies worldwide and of those, only 24,600 resulted in live births.

The drug was licensed for distribution in the UK by Distillers Company (Biochemicals) Ltd in April 1958, mostly under the trade name Distaval. By the end of November 1961, it had been officially withdrawn from use in both countries.

We may never know exactly how many people were impacted by thalidomide, but conservative figures indicate that there were around 147,000 thalidomide-affected pregnancies worldwide and of those, only 24,600 resulted in live births. In the UK, out of the 12,000 recorded thalidomide pregnancies, only 2,000 resulted in live births. And most babies did not survive infancy. There are just over 450 survivors alive in the UK in 2021.

Gloria was only 19 years old when she gave birth to her son, who was born with no legs. It was almost ten years later that she learned that the medication for morning sickness that her GP had prescribed was Distaval.

Babies were most typically born with missing or shortened limbs, but the drug also affected the eyes, ears, face, spine and some internal organs; together referred to as thalidomide embryopathy. Their plight was raised in the UK law courts and in a media campaign in the 1970s led by Harold Evans, editor of the Sunday Times newspaper, but it took years to establish adequate compensation and care.

Prescribing thalidomide in the UK

Mothers who took thalidomide are now mostly in their 80s and 90s, but they remember the details of this moment in their lives with perfect clarity. Rukhiben, for instance, had just arrived in the UK from India and was prescribed thalidomide during pregnancy to help her acclimatise to her new environment.

Beatrice had bronchitis and recalls telling her doctor she was pregnant at the time: “He said to me this would be all right and I explained to him that I was pregnant and he said to me, ‘Oh, it won’t harm you, you’ll be fine.’ And I believed him, as you do, doctors them days.” The general lack of information and an inherent unwillingness to question your family doctor meant that most people dutifully took their medicine.

Maureen W recalls how she was persuaded to take the pills or risk miscarriage: “My GP came round one evening because I had been continuously sick, and she said, ‘If we don’t do something to stop this sickness, you could lose this baby.’ And she just passed me over a small number of pills that she had in her bag... I only took a couple.”

Mothers often mention how surprised they were that after they took just a small number of pills their child was affected, often severely. Doctors later discovered that taking just one or two tablets at a key stage in foetal development could cause significant damage to the unborn baby.

Rukhiben arrived in the UK from India and was prescribed thalidomide during pregnancy to help her acclimatise to her new environment.

Maureen S was given a sample dose by her doctor, and found it helped her insomnia: “I think I took about three doses… it was a small sample bottle… A pinky liquid. And it was so successful that I said to my husband, ‘Michael you ought to get some more of this’… and he trotted off to the chemist and chemist said, ‘I can’t possibly give you any of that. It’s been withdrawn from sale.’”

The reason for its removal was due to international reports of children being born with a range of impairments and organ failure. But both the drug companies and the medical establishment were reluctant to share information with the public, even with those directly affected.

Doctors know best

Some parents were furious with their prescribing doctor, but in general most felt that their family doctor was as much in the dark as they were about the effects of thalidomide and had prescribed it in good faith. What was perhaps less forgivable was how vital information was withheld from the parents in the first few weeks and months after the baby was born.

June had a difficult first pregnancy, suffered from severe morning sickness throughout and was prescribed thalidomide. Her daughter was born with arm impairments, which June didn’t attribute to the ‘safe’ drug she had been prescribed until she started hearing stories in the news about thalidomide babies.

She decided to confront her family doctor about whether her baby was affected by thalidomide and was appalled to discover that she was, but that the doctor had withheld this information “for her own good”.

June.

Grief and loss

It is clear that many in the medical profession were as unprepared as their patients for coping with the effects of thalidomide. Doctors and nurses working in maternity care had rarely seen such disabled babies and often did not know how to respond to or support the parents.

Some of the most difficult experiences were of mothers whose babies had died. They frequently found themselves left alone to cope with feelings of guilt, loss and grief. Artist Rozanne found out ten days after giving birth that her daughter, who didn’t survive birth, had been named and buried without her knowledge. The experience affected her whole life and influenced several of her artworks.

Rozanne.

Many more families who lost a child may never have been told about the role thalidomide played in their tragedy; others, like Frederic, died when they were just babies, before the long campaigns for justice saw results. Their families were offered neither counselling nor compensation. Frederic’s sister Christine reports that their mother Gertrud suffered from poor mental health for the rest of her life after Frederic’s death.

Over 10,000 grieving families in the UK lost a child at birth or shortly after as a result of thalidomide, and around 115,000 more deaths occurred worldwide.

About the contributors

Ruth Blue

Dr Ruth Blue is a freelance writer, researcher and oral historian with a PhD in fine art from the Slade School of Fine Art. She worked for Wellcome for 17 years, where she began working with thalidomide survivors in 2013, collecting their stories, photographs and artefacts. She has continued this work for the Thalidomide Society.

Hollie Chastain

Hollie Chastain is a mixed-media artist and award-winning illustrator living and working in Chattanooga, Tennessee. Coming from both a graphic-design and studio-art background, her work has a storytelling quality, mixing found material, strong graphic elements and modern palettes. Along with gallery work, she has illustrated work for Smithsonian Magazine, Warner Music and the Oxford American, among others, and authored and illustrated a book published in 2017. She currently works from a home studio with her husband Eric, two children, two cats and two dogs.