When, in 1959, a quick new pregnancy-testing drug replaced the time-consuming methods available previously, doctors happily prescribed it. But an unusually high number of babies with disabilities were born to mothers who took the drug. Despite increasing safety concerns, Primodos wasn’t withdrawn until 1977 and attempts to uncover the truth about the drug, and get justice for those affected by it, continue today. At the story’s heart are two women who battled through decades of medical paternalism: Marie Lyon, who took Primodos, and Dr Isabel Gal, the scientist who first raised the alarm.

At the start of 1970, Marie Lyon walked into a doctor’s surgery in St Helens, north-west England suspecting she was pregnant with her first child. She was 24, married to a police officer and working as a secretary at Pilkington, a glass manufacturer and the town’s biggest employer – and she was scared.

Shy unless in the company of her gang of close female friends, Marie had never had a medical examination like this before. And beyond accounts from these friends, passed around like paperback books, she didn’t know what to expect from one that would determine whether or not she was going to have a baby.

Before the pee-on-a-stick test we have now, confirming pregnancy was complicated. From the late 1920s to the early 1960s, women’s urine was collected and sent off to be injected into mice, rabbits and frogs. If the animals ovulated, went into heat or spawned eggs, the woman was pregnant.

The mice and rabbits were killed afterwards – “the rabbit died” emerged as a euphemism for “I’m pregnant” – and, as the frog test took over as a quicker, simpler and non-fatal alternative, Xenopus frogs were caught and bred in their thousands. Eventually, in vivo gave way to in vitro and women’s urine was sent off to be filtered into test tubes instead.

These tests were safe and accurate, but they were patently convoluted. There was demand for a more convenient alternative.

Marie Lyon as a young woman, including cutting the cake on her 21st birthday. Back then Marie was shy, unless in the company of her gang of close female friends.

Marie sat in the waiting room, gearing up to pee in a plastic cup, perhaps to undress in front of a stern doctor. The doctor was delayed. Marie dithered.

“You can go in now,” the receptionist said eventually.

“Just take these two tablets,” said the doctor. “One today, one tomorrow – 12 hours apart – and if nothing happens, you’re pregnant.”

“Really? What about…”

“Oh, we don’t do that now.”

She was prescribed Primodos, a hormone-based pregnancy test. The idea was that, if you weren’t pregnant, it would induce something like a period. Marie didn’t bleed. In October, her daughter Sarah was born. Sarah’s left arm wasn’t fully formed; the tiny palm and fingers that had grown where it stopped, at her elbow, were amputated just over a year later.

Marie and her daughter Sarah. When she was born, Sarah’s left arm wasn’t fully formed; the tiny palm and fingers that had grown where it stopped, at her elbow, were amputated just over a year later.

Raising a red flag

Three years earlier, in 1967, Dr Isabel Gal, a paediatrician at Queen Mary’s hospital in Carshalton, had co-authored a study in the journal Nature suggesting a potential link between hormone pregnancy tests (HPTs) and birth defects. It had found that, of 100 babies born with myelomeningocele (a type of spina bifida) or hydrocephalus, 19 of their mothers had taken oral tablets, including Primodos, to confirm pregnancy. This compared to only four mothers in a control group of 100 healthy babies.

Isabel Gal had arrived in the UK in 1956. Born into a Jewish family in Hungary, she’d been imprisoned at Auschwitz with her mother and two sisters during the Holocaust. Her father had been killed. After the war, Gal qualified as a doctor and worked in Budapest before fleeing the Hungarian Revolution. She retrained in Edinburgh and then eventually moved down to London with her husband Endre and daughter Kathy.

Endre and Isabel had met as children and maintained on-and-off contact for years before marrying. He had been conscripted to fight with the Russians during the war, marching 1,000km to the north and then all the way back when it was over. Endre had been in love with Isabel for a long time. He asked her to marry him five times before she said yes.

Now, in October 1967, they all lived together on the Fairways estate in Teddington, with a flat, grassy common on the doorstep and the River Thames at the back door. Dr Gal was concerned about the results of her study into hormone pregnancy tests. It wasn’t conclusive, but it was alarming. There was an urgent need for further testing, and she hoped publication in this leading journal would facilitate it.

It doesn’t sound great: a pill to determine pregnancy made up of the same components as pills designed to stop pregnancy.

Primodos, the most commonly used hormone pregnancy test in the UK, was produced by German pharmaceutical brand Schering. It was first prescribed in the UK at the tail end of the 1950s, and, by 1967, was routinely offered as an alternative, home-based pregnancy test. It contained norethisterone acetate and ethinylestradiol: progestogen and oestrogen respectively, which are found also in contraceptive and morning-after pills.

It doesn’t sound great: a pill to determine pregnancy made up of the same components as pills designed to stop pregnancy. Primodos, we now know, typically contained 40 times the amount of progestogen/norethisterone found in today’s oral contraceptives. It had another use in other countries – as an abortion pill.

Dr Gal’s co-author had written to a new advisory body, the Committee on Safety of Drugs (CSD), with advance warning of her findings earlier in the year. She herself had met and struck up a correspondence with its senior medical officer, Bill Inman. By the time Marie had her baby in 1970, Gal was pages and pages into her dialogue with Inman – and nearly out of a job.

From the late 1920s to the early 1960s, women’s urine was injected into mice, rabbits and frogs to establish whether or not they were pregnant. This bookmark was produced to advertise the Primodos pregnancy test, arguing it was cheaper and faster than the frog method.

Authorities conspire to conceal

It would be just under eight years from the publication of Gal’s study before the Committee (which became the Committee on Safety of Medicines, CSM, in 1970) issued a warning saying hormone pregnancy tests “may cause congenital abnormalities”, and almost 11 before Primodos was taken off the market for good.

It’s estimated that, throughout the 1960s and 70s, well over a million women in the UK alone were given hormone pregnancy tests, although the exact number may never be known. These tests are associated with an increased risk of birth defects, including heart, nervous system and musculoskeletal malformations, and a higher incidence of miscarriage, stillbirth and infant deaths.

Is this ringing any bells? As one Medical Research Council doctor wrote to another on 23 June 1967, the HPT saga looked “as if it could be another thalidomide story”.

Thalidomide was a drug that some pregnant women took to treat morning sickness in the late 1950s and early 60s. It led to stillbirths, miscarriages and birth defects. The CSD had been set up by the government to make sure nothing like it ever happened again.

In this, it failed. Instead of acting on the association between birth defects and hormone pregnancy tests like Primodos, one committee member actually suppressed efforts to warn those taking it, collaborating not with patients but with Schering.

The German multinational pharmaceutical company has since been absorbed into Bayer, which today manufactures the Jaydess, Kyleena and Mirena coils, and contraceptive pills including Yasmin. Bayer denies there is a link between birth defects and Primodos, the noxious stepsister of these contemporary contraceptives.

A dereliction of duty

The contraceptive pill changed everything. It was first made available on the NHS in the early 1960s. The 1967 Family Planning Act gave more people – primarily married women and good liars with pound-shop wedding rings – access to the pill, and then, from 1974, NHS contraceptive advice and supplies were available whether you were married or not.

Gal had noted the likeness between the pill and hormone pregnancy tests in her letter to Nature: “Contraceptive pills, which have been subject to a very careful scrutiny, have a similar composition, but the dose and balance of the constituents are different.”

It seemed a salient, if unremarkable, observation: a sentence of context. It was just one line but, in the world of this story – the shuffling egos and profit-and-loss sheets, the women for whom oestrogen and progestogen meant not freedom but guilt and shame, the professional and emotional landscape of one doctor’s life – it made a big difference.

In ‘A historical argument for regulatory failure in the case of Primodos and other hormone pregnancy tests’, historian of science Jesse Olszynko-Gryn suggests that the advent of the contraceptive pill, and panic over its use and effects, stalled the banning of Primodos. He and four co-authors argue that Bill Inman “prioritised averting a thalidomide-type pill scare at a time when oral contraception was an economically important drug… and medical paternalism generally militated against informed consent”.

It was crucial that the rollout of the contraceptive pill was not derailed – for commercial reasons as well as in the context of a perceived overpopulation crisis. The pill was already controversial; people worried about health impacts as much as they worried about going to hell for taking it. Anxiety over Primodos, with its similar components, would conceivably stall take-up further.

Olszynko-Gryn is one of several people tracing back through a paper trail now entrusted to the dusty depths of national archives. Their research is vindicating Dr Gal and revealing another side to Dr Inman – a man lauded within the medical establishment for introducing the “yellow card” early warning scheme (a system for recording suspected side effects to medicines) and the mini-pill.

Another person following this paper trail is Marie Lyon who, since becoming chair of the Association for Children Damaged by Hormone Pregnancy Tests (ACDHPT) around ten years ago, has become consumed by her quest for answers and acknowledgment.

Tracking references from document to document, Marie uncovered a web of phrases, names and characters. The documents she and others unearthed revealed something that, to them, looked like a cover-up.

The detective work begins

It’s snowing on the March day I travel up to Wigan to meet Marie. She is 76 now, her daughter Sarah 53. Marie is remarried, to Mike, who brings crumpets and coffee throughout our two-hour conversation. Watching snowflakes brushing the outside of the conservatory, in front of an electric fire, she tells me a story she’s told a hundred times before. She does so with all the energy – all the seething rage at the injustice of it – of someone telling it for the first time.

Marie started at the National Archives, tapping phrases into a computer and leafing through the files that came up. “It was hit and miss. Because I just said, right, look for anything that says ‘hormone pregnancy test’, ‘oral contraceptives’, ‘ethinylestradiol’; buzzwords… That was all I could go on. I didn’t know anything else at the time. I know a lot more now – I know a lot more words!”

Tracking references from document to document, she uncovered a web of phrases, names, characters. “William Inman, Doctor Smithells… All these people were like a little clique, and that clique then led straight into Schering [now Bayer].”

All signs pointed to Berlin, to a red-brick, former factory building that now housed the state archives. Marie collaborated with the Coalition against Bayer Dangers to trawl through 7,000 pages of evidence stored in the Landesarchiv. They made sense of the German text while she looked at the English. “When I got the disk and started to look through it, I couldn’t stop. Mike was going mad because he kept saying, ‘It’s nearly midnight,’ but I literally could not stop.”

Destroying the evidence

The documents unearthed by Marie and others revealed something that, to them, looked like a cover-up. There are numerous letters, but the following quotations are representative. In summary:

Inman encourages Gal to publish her study. In December 1967, he writes to her: “I frankly do not think that they [HPTs] are sufficiently useful when compared with other biological methods to justify even the slightest risk of teterogeneity [potential to increase the risk of birth defects and development disorders].”

Gal chases Inman over the course of several years to see whether he is making progress with an additional study. In March 1968 she writes: “I should be very interested to know whether you have been continuing to collect further information on the use of the pregnancy test.”

Inman responds with assurances and excuses and then, when his own research suggests a 5:1 risk of malformations associated with HPTs, he appears to start covering his tracks.

In August 1975, he writes to J J A Reid, Deputy Chief Medical Officer: “The Department would be vulnerable if Dr Gal launches an attack on the Committee… It may not have escaped her notice that, if the relative risks suggested by our publication turn out to be true, several thousand congenitally abnormal babies have been born as a result of hormone pregnancy tests carried out after publication of her paper.”

In October 1975, again to Reid, he adds: “Isabel Gal is an intelligent, dedicated but rather sad little person. I dealt with her sympathetically to the best of my ability, but I do not believe we have heard the last of this matter.”

Everything was painstakingly pieced together by Sky News. Its 2017 documentary ‘Primodos: The Secret Drug Scandal’ shows that Inman immediately took his findings to Schering, not to urge it to recall the drug, but so that the pharmaceutical company could “take measures to avoid medico-legal problems”. He then destroyed his research to prevent it from becoming the basis of any future claims for compensation.

A 1978 Schering memo reads: “[Dr Inman] has destroyed all the material on which his investigation is based, or made it unrecognisable, which makes it impossible to trace the individual cases taken into the investigation. I understood from Dr Inman that he did this to prevent individual claims from using this material.”

Four years later, in 1982, a lawsuit brought by the ACDHPT against Schering collapsed due to there being no realistic possibility of proving Primodos caused the alleged birth defects.

Marie’s daughter, Sarah, as a girl, and her prosthetic arm. Hormone pregnancy tests are associated with an increased risk of birth defects, including heart, nervous system and musculoskeletal malformations.

The human fallout

“Dr Gal never, ever forgave herself for the sentence [in the article she published in Nature, about there being] the same components in Primodos as the oral contraceptive pill. That killed it stone dead. This is why we’re fighting today,” says Marie. “We were just sacrificed really: collateral damage… ‘It’s only a few thousand of them; this could be millions of births in, you know, 12 months.’”

The medical establishment’s desire to promote the contraceptive pill is one reason it took so long to ban Primodos. One could also argue that Dr Gal’s being a woman, being foreign and being Jewish potentially made it easier to brush her concerns aside. But at the root of all of this is surely negligence, corruption, and lack of accountability.

“The reason that she couldn’t do it is because people prevented her from doing it,” says Dr Gal’s daughter Kathy, when, on a warm day in mid-April, daffodils and red tulips in bloom, I visit her in the same Fairways house she grew up in.

“The way she was treated was fantastically upsetting, but it wasn’t because she was a woman, just because she was a woman. Of course, it was a lot because these people were threatened by what she was saying… the consequences of it actually coming out and so on would cost millions.”

Isabel and Endre’s only child, Kathy, is an architect, her childhood bedroom now her office. She remembers what it was like watching Dr Gal’s gradual ostracisation from the medical community, living alongside the woman behind the letters. “I have not been working at Charlotte’s [hospital] since 1972,” Gal wrote to Inman in 1975. “Most of the time you can find me at home.”

“She never got over it. Always massively resentful,” says Kathy. “I don’t think resentful actually covers the depth of emotion.”

Despite this, Kathy says her mother’s integrity remained intact. In one of the jobs she took because she had to, at a pharmaceutical company in Somerset, Dr Gal kicked up a fuss about something “not very straight” going on. A commercial decision by the company, perhaps. She was dismissed.

Celebrating the work of Isabel Gal

Marie Lyon contacted Dr Gal for the first time in 2013, asking whether she could keep her updated on the ACDHPT. “I know that Primodos has had a huge impact on your life and would fully understand if you do not wish to be informed of any developments,” she wrote, “but I just wanted to let you know that you will never be forgotten by me, and by the other members of the Association.”

With the evidence she had assembled, Marie had reignited the campaign for legal redress that had fallen apart back in the 1980s. A cross-party group of MPs convened in June 2014, and Marie and Isabel met for the first and last time.

“We got flowers, and we said to everyone: ‘This is a celebration of Dr Gal who, really, lost her whole career because of this.’ And everybody was clapping. She was just so moved.”

Endre pushed his wife, who was in a wheelchair by this point, over to Marie at the end. For a long time, Dr Gal said, she hadn’t known that anyone was still pursuing justice. “I’m so, so glad you are.”

Dr Gal died in 2017 at the age of 92. By the time the Sky documentary came out, she could no longer speak due to vascular dementia, but Kathy showed it to her. “She definitely recognised what was going on,” she says. Endre died 14 weeks after Isabel.

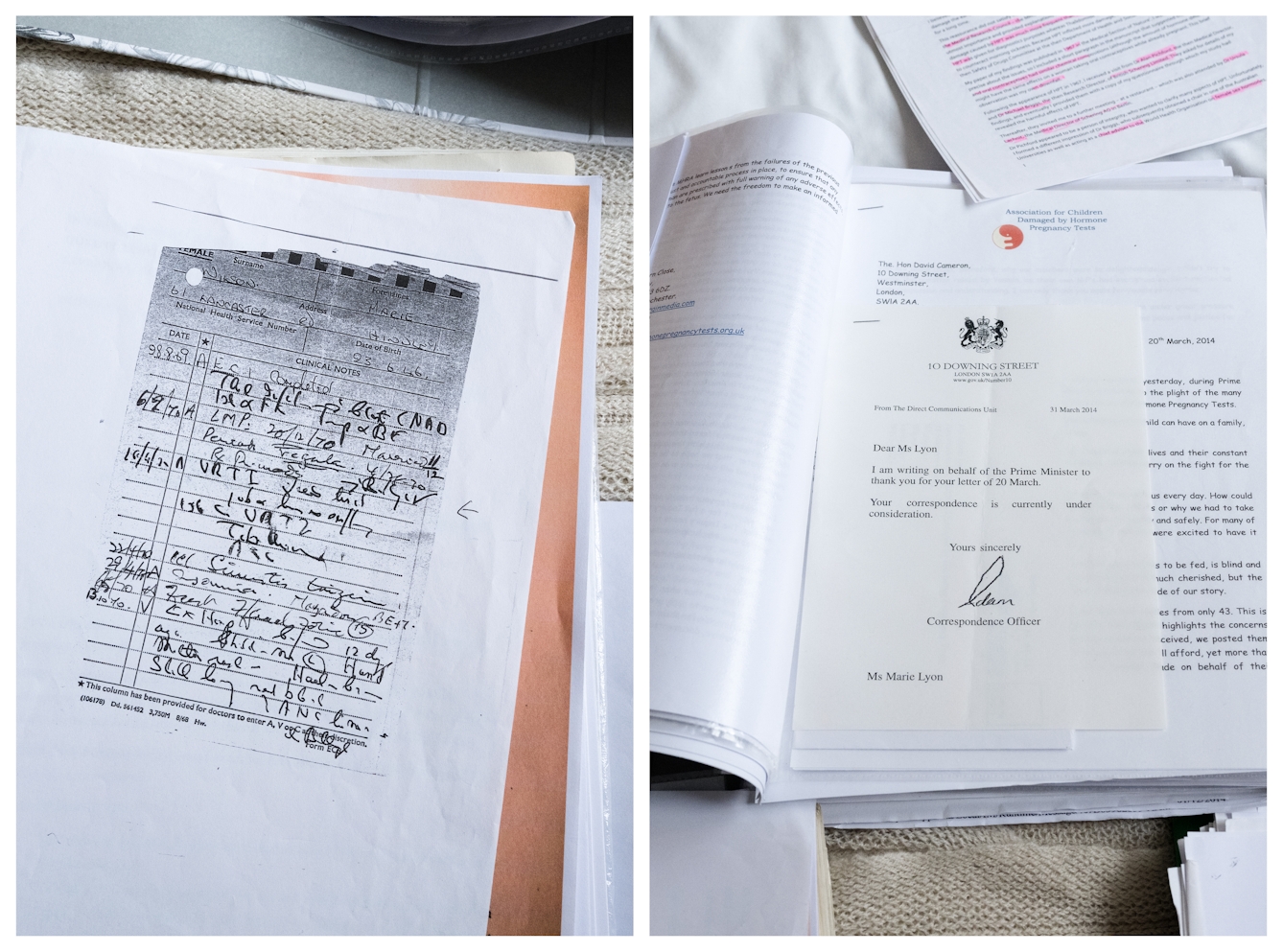

Marie's 1969/70 medical records detailing Primodos, and her correspondence with 10 Downing Street in 2014. Marie has become consumed by her quest for answers and acknowledgment.

Three reports and an apology

It’s been one step forwards, two steps back in the seven years since Gal’s death.

A late-2017 independent expert working-group report commissioned by the government found no causal link between HPT use and birth defects.

Dismayed, Marie contacted University of Oxford epidemiologist Carl Heneghan. A systematic review by Heneghan and others was published in 2018 and found that “use of oral HPTs in pregnancy is associated with increased risks of congenital malformations”.

Meanwhile, then Prime Minister Theresa May had grown sceptical about the expert working group report and commissioned a further investigation. ‘First Do No Harm’ came out in 2020 and concluded that Primodos should have been removed from the market in 1967. The government offered a “fulsome apology”.

But an apology is not the same as admitting liability in a court of law, it turns out. In 2023, Marie was still fighting, and she was increasingly desperate.

When Marie and I first met, the ACDHPT’s lawsuit – against Bayer and others, including the Department of Health for failing to implement adequate regulation – was still trundling along. She told me that 22 ACDHPT members had died since the reopening of proceedings: 18 mothers and four disabled children.

At the start of May, the defendants argued for a strike out. There was, they said, still no provable link. Plus, they added, the ACDHPT would never amass the funds needed to see the litigation through. While the ACDHPT is a charity reliant on donations, the state and drug companies presumably have deep coffers and throngs of lawyers to draw on.

On 26 May 2023, the strike-out request was granted. The case brought by over 100 HPT victims was thrown out of court.

Mrs Justice Yip said: "I recognise the profound disappointment my judgement will bring for the claimants. They believe, and will no doubt continue to believe, that HPTs were the cause of the birth defects and the loss of the babies which they have suffered. No one has been able to confirm definitively that this belief is wrong.”

Marie became chair of the Association for Children Damaged by Hormone Pregnancy Tests a decade ago. She is no longer the timid 24-year-old waiting at the doctor’s surgery, and will – somehow – continue her quest for justice.

An avenue to justice closes

“I always thought,” Marie says, “if someone had a grievance, then it would be sorted out: people are honest, and if somebody does something wrong, they’d admit it and try to put it right. I had no idea of the lengths that people will go to to actually protect themselves.”

The logic and morality that most people live their lives by is absent in the bureaucratic, corporate and legal arenas she contends with; the guilt so many of the Association feel is not obviously reflected back by the officials and executives who did wrong.

In many ways, the 2023 appeal for recognition and compensation was simply a rerun of the first, back in 1982. But Marie is no longer the timid 24-year-old waiting at the doctor’s surgery and will – somehow – keep going.

After the trial, the government and Bayer argued that Primodos campaigners should commit to never making another claim, or else pay seven figures in legal costs.

Two dozen members of the ACDHPT travelled to London to attend the costs hearing in person on 12 October 2023. Fearing the loss of their homes, 100-plus claimants had to agree to the terms – and thus now, officially, this avenue to justice is closed.

In February 2024, Patient Safety Commissioner (PSC) Henrietta Hughes publicly launched a report calling for compensation for victims of two other women’s health scandals: sodium valproate and vaginal mesh. Primodos was glaringly absent.

“The PSC’s role is to oversee patient safety, yet not one member of our Primodos families has been contacted to ensure their patient safety needs are met,” says Marie.

“Our families have sole responsibility for the cost of medication and devices necessary to prevent physical and mental health deterioration. Shameful.”

The most viable remaining route to justice is through politics. With a general election due later in 2024, and the Post Office scandal proving a deeply revealing moment for many in public office, there is hope parties will make manifesto commitments to offer redress.

So far, so silent.

About the contributors

Florence Wildblood

Florence Wildblood is a journalist covering media and corruption. She works primarily for Byline Media’s investigations arm and its new sister book publisher, Yellow Press. She is studying for an MPhil in the Sociology of Media and Culture at Cambridge University.

Kathleen Arundell

Kathleen is a freelance photographer working in the culture and heritage sector. She works in a range of museums across London, and loves all things science and art.