When Jaydee Seaforth decided to seek medical help to alleviate her uncomfortable gut issues, she was in for a shock. It seemed that most of her favourite foods caused problems, and this included the home-cooked Caribbean dishes that made up much of her diet. Dismayed at the new blandness of her meals, Jaydee hopes to see more options for IBS-friendly foods.

Christmas in a Caribbean household may vary region to region. But as sure as there will be roast potatoes on my plate – and those of millions of other British families – come dinner time on the 25th, our Caribbean Christmas breakfast would be incomplete without fried dumplings. A fluffy but crisp doughy ball of goodness, made with flour, salt and baking powder, similar to Guyanese bakes or African American ‘biscuits’, and now completely off-limits due to my sensitive gut.

Fried dumplings aren’t the only Christmas Day essential rejected by my strict stomach. I couldn’t be a proper Black Brit without my family’s meals being a joyful fusion of our flavourful Caribbean roots and warm British staples. Stuffing, Yorkshire puddings, and my nan’s controversial but beloved pigs in blankets all contain wheat, which I struggle to digest. But this aversion to the foods I was raised on did not begin this year, and extends way beyond Christmas Day.

Tummy troubles

My secondary school was undeniably British. Our motto was “serve and obey”, the main hall looked like an exact replica of Hogwarts’ dining hall, and on Fridays, we ate fish and chips.

By the time I reached Year 10, I was much too cool for school dinners. I usually opted for a greasy chicken-shop meal on my way home. But on Fridays I’d be the first one in line, dinner tray at the ready, salivating over the warm aroma of freshly fried fish. I’d hold up the queue trying to pick out the best-looking one (the crispier the better) and plead with the lunch ladies to forgo the one-side-per-meal rule so I could delight in mixing my mushy peas with my baked beans.

The highlight of my week was drizzling a slightly stale lemon wedge over the entirety of my meal, wolfing it down, and then presenting a plate on the dish rack that looked like it had just come out of the dishwasher.

However, for those who had to share the next 90 minutes caged in a classroom with me, my Friday ritual was cause for deep concern. I’d waddle into the lesson blissful and bloated, then immediately sit by the nearest window.

In the earlier years, I’d attempt to ignore the deep gurgling. Shifting my weight from one leg to another, I’d hold my swollen stomach, pleading with any god who’d listen to grant me the strength needed not to toot. But as time went on, I decided for the sake of my gut I had to allow my classmates to see a side of me my family were already far too familiar with – I passed wind a lot.

"I had to allow my classmates to see a side of me my family were already far too familiar with – I passed wind a lot."

Though Fridays were undeniably the worst for flatulence, it didn’t really seem to matter what I ate. Whether it was beans, Jamaican brown stew chicken or a simple sandwich, I’d end up on the toilet.

While studies have shown that technically there is no ‘normal’ frequency for human bowel movements, most people fall between as much as three times a day to as little as three times a week. An average day for me could mean I’d already cleared the highest healthy frequency before 11 am. It was undeniable that something wasn’t right. But like a true pooper trooper, my diet remained pretty much unchanged until I was in my early 20s.

Favourite foods off-limits

The first thing on the food pyramid to be axed was dairy. With all the available cow’s-milk substitutes, it didn’t seem like a life-altering decision to make. Though I do mourn the loss of Caribbean macaroni pie (a firmer and superior version of mac and cheese that’s a staple at any West Indian BBQ), along with my nan’s condensed-milk brewed teas.

Dairy was soon followed by other eliminations. Shortly after ingesting a family-sized pack of Thai sweet chilli potato crisps, I found myself at the GP, being bluntly informed that I may have a gluten intolerance. It turned out that it wasn’t only the cheese in the macaroni pie causing me problems: the macaroni itself was also an enemy of my digestion.

To break down our food, our bodies use enzymes. However, these helpful proteins cannot completely break down gluten. Instead, the indigestible gluten hangs out in the small intestine. According to weight-management expert Dr Selvi Rajagopal, this is no issue for most people, but in some “can trigger a severe autoimmune response or other unpleasant symptoms”. Symptoms of which include stomach aches, diarrhoea, bloating and flatulence.

So along with all my favourite dairy products, I also had to say goodbye to all foods and drinks containing wheat. That meant no bread, no pasta, no cereal, among a range of other food staples. Though options for substitutes aren’t yet as vast as those for people with lactose intolerance, they do exist. I spent the next few months trying out different gluten-free breads, to find just one that didn’t taste like cardboard, and pasta that wasn’t hard as nails.

Eating out was becoming difficult. Dairy-free options could be found at some restaurants in the vegan section. And some menus highlighted which foods were gluten-free (usually only a salad or chips).

But harder than finding a safe meal while out was being able to eat any home-cooked meal with my family. No more dumplings, fried or boiled. Hard-dough bread was a thing of the past. Even curry powder contained gluten!

The language of food

My dietary changes were challenging, but I wouldn’t know true loss until I was told that what I believed was just lactose and gluten intolerance was actually irritable bowel syndrome (IBS). Alongside the already gargantuan list of foods I couldn’t eat because my body refuses to digest gluten, my poor intestines struggled with all types of fermentable oligosaccharides, disaccharides, monosaccharides and polyols (also known as FODMAPs).

This diagnosis offered some relief: I finally understood why, while I attempted to eat healthily, I would still end up extremely bloated (broccoli, lentils, apples, grapes and a comically long list of other fruits and veggies are all high-FODMAP foods). But this new revelation meant that I could no longer consume onions or garlic. Which to someone hailing from the Caribbean was akin to being told I could no longer breathe air.

As any person of colour is aware, onion and garlic are the base of any decent meal. Whether I was making soup, curry or just a simple breakfast, no meal was complete without sautéed onions and garlic. The only thing that had been getting me through being unable to eat gluten or lactose was that I could season my meals to taste identical to the foods I grew up with. But this was no longer the case. Having IBS began to feel like I was effectively being locked out of my own culture.

"I felt as bland, inflexible and boring as the food I had little choice but to eat."

Food is a language. It tells people where you’re from in ways that even language can’t. Colonisation saw the erasure of so much indigenous culture, from religions to ways of dressing and speaking. But something the colonisers failed to destroy was the way we eat, which can be seen so vividly in the similarities between African American soul food and West Indian and African cuisine.

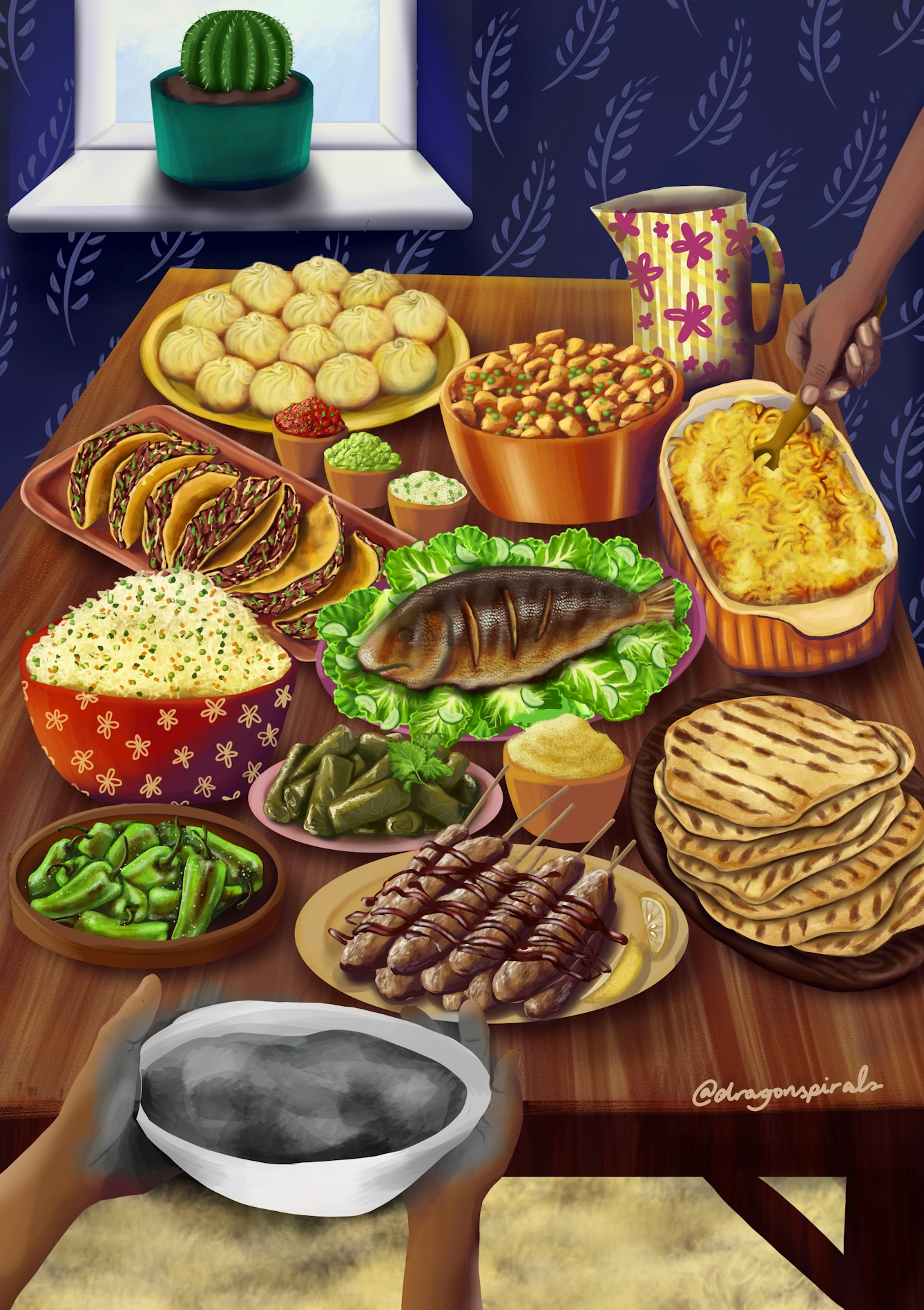

Food can tell you whether you live in a colder or warmer climate – it is thought that people in warmer countries have spicier food because of the antimicrobial properties found in peppers, which help to stop food from inevitably spoiling due to the heat. Food can tell a person about their heritage – Trinidadian food, for example, is a wonderful fusion of Caribbean and Indian flavours, beautifully reflecting the racial makeup of the island. The food from where I’m from is a vibrant, colourful, spicy melting pot of flavours, just like the people. Without it, I felt as bland, inflexible and boring as the food I had little choice but to eat.

Doctors didn’t seem to understand why cutting out onion and garlic-rich foods was such an issue, or why I complained about my nutritional plan having a lack of culturally aligned foods.

I had no idea how much this would affect me. Doctors didn’t seem to understand why cutting out onion and garlic-rich foods was such an issue, or why I complained about my nutritional plan having a lack of culturally aligned foods.

The challenges of an IBS-friendly diet

Even when I ate everything that was considered safe, I’d still find myself having flare-ups. This was due to IBS also being triggered by stress. Besides having IBS, I’m also neurodivergent. I struggle immensely with change, particularly when it comes to routine. If I like a certain food or drink, I will consume those products obsessively until the day my brain decides I’ve overdone it. Certain textures and tastes are enough to make me feel physically ill, so, like most neurodivergent people, I had a list of “safe foods”. Almost all of my safe foods were now off the menu.

To say the start of my new journey into having good gut health has been difficult would be an understatement. I regularly fall back into old patterns of eating, I get frustrated, and I’ve cried in a supermarket on more than one occasion.

But this Christmas, I'm happy to report that my irritable bowels haven’t taken away all my favourites. Sorrel, a tart Jamaican tea made from hibiscus, ginger, allspice and white rum, is a festive way to support digestion. Gluten-free flour means I can still have fried dumplings. Paxo has created a gluten-free stuffing mix. And though I may not be able to eat my great-aunt's rum cake, there is a range of gluten- and lactose-free desserts available from all major supermarkets that I plan on exploring.

I am on a mission to make gut health a priority. Not just for my gut but for the digestive systems of people of colour who grapple with the same issues I do. We need to be included in conversations about diet because without our voices we will never see our cultures reflected in the options for IBS-friendly foods.

About the contributors

Jaydee Seaforth

Jaydee Seaforth is a multidisciplinary writer and educator from south London. She has written for publications such as Black Ballad, BBC3 and Oxford University-founded print magazine Onyx! With an interest in activism, social injustice, and all forms of human interaction, she aims to make you feel less alone.

Rahul Radja

Rahul is an artist, designer and web developer from the UK. As a queer, trans, disabled, neurodivergent Indian, Rahul is devoted to ensuring that people from marginalised communities are able to share their experiences and find community and acceptance.