For 30 years, Mary Bishop lived in Netherne Asylum in Surrey, where she produced hundreds of paintings. Writer and artist Rose Ruane explores how surveillance by medical staff and Bishop’s own intensely critical self-scrutiny informed the art she created.

Mary Bishop and the surveillant gaze

Words by Rose Ruaneartwork by Mary Bishopaverage reading time 8 minutes

- Article

Whenever I draw a face, I begin with one eye and work outwards. Unthinkingly, instinctively, I’ve always drawn people that way, despite it being inimical to everything I’ve ever been taught about how to start representing a human.

Recently, I’ve had cause to analyse why, and have concluded that it creates an obligation to the drawing which ensures that I’ll complete it. Everything that has an eye has a soul of some sort, and everything with a soul demands responsible treatment.

Some experiences of viewing art are monodirectional – the act of looking resides entirely within the viewer, but some art has a particular kind of intensity or aura which leaves us feeling as though the work has returned our gaze. This was how I felt the first time I saw the paintings created by Mary Bishop in the art therapy studio at Netherne Asylum, now Netherne Hospital, where she was compelled to live for several decades – the majority of her adult life – having entered the hospital in her early 30s, after a period of working at Orpington radar station during World War II.

I felt they were ensouled. They fostered an immediate sense of responsibility. Her art is profoundly expressive: transmissions of distress, palpably charged with a suffering so urgent that it seems to collapse the decades between making and seeing. Even removed from the circumstances of their making, her paintings impart a certainty to the viewer that they are an attempt to communicate deep feeling.

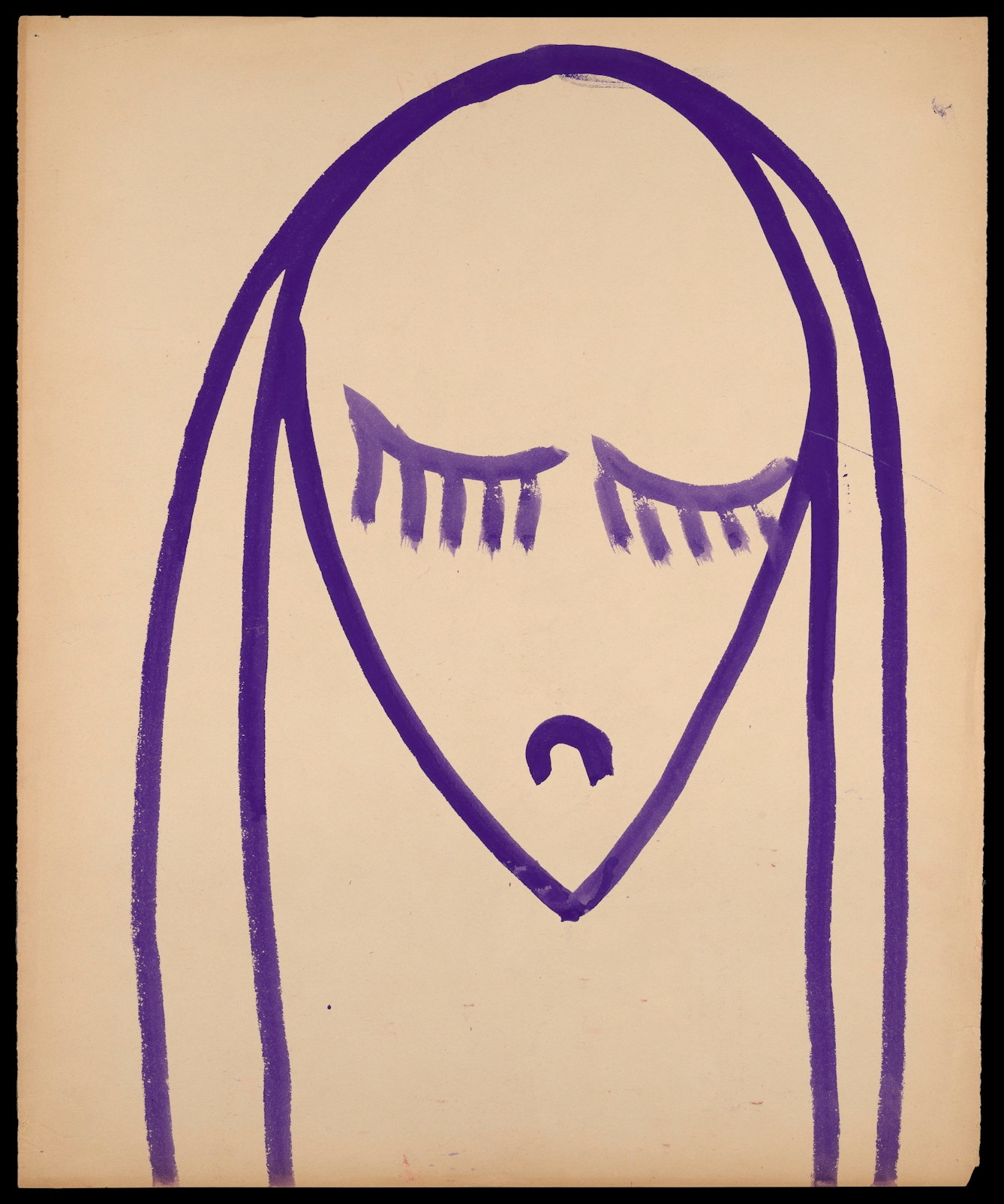

A young woman looking downwards in shame. Watercolour. 1968. Mary Bishop. (Artwork titled by cataloguer for identification.)

The birth of art as therapy

Without necessarily considering herself an artist, Mary created hundreds of these paintings during her time at Netherne. First established in 1946, the art therapy studio was run by Edward Adamson, initially as an experiment to see if artistic activity might be an aid to diagnosis. However, it quickly evolved into a space that supported free, unguided expression as a form of therapy; a place that afforded an opportunity to articulate thoughts and emotions which might evade other forms of language.

The studio was the first in a UK psychiatric hospital, and Netherne was a comparatively progressive institution for the period. The hospital’s minute books essay the workings of a management committee that passionately believed that the arts in all their forms were as important to the wellbeing of those who resided there as any medical intervention.

However, Netherne, like many 20th-century psychiatric hospitals, was a large, dark building on a hill, distant from the comings and goings of daily life. Long, echoing corridors, locked wards and dingy décor gave it an air of high gothic; a place where treatments we now recognise as forms of institutional violence were inflicted on the residents. The tightly packed wards made the abject lack of privacy even more pronounced.

To live at Netherne was to exist in a perpetual state of surveillance: to be examined by doctors, watched constantly by nurses, and to be accompanied everywhere, even to the lavatory and when washing, unless otherwise judged fit to go alone. Privacy and agency were privileges to be earned by ‘good’, compliant conduct.

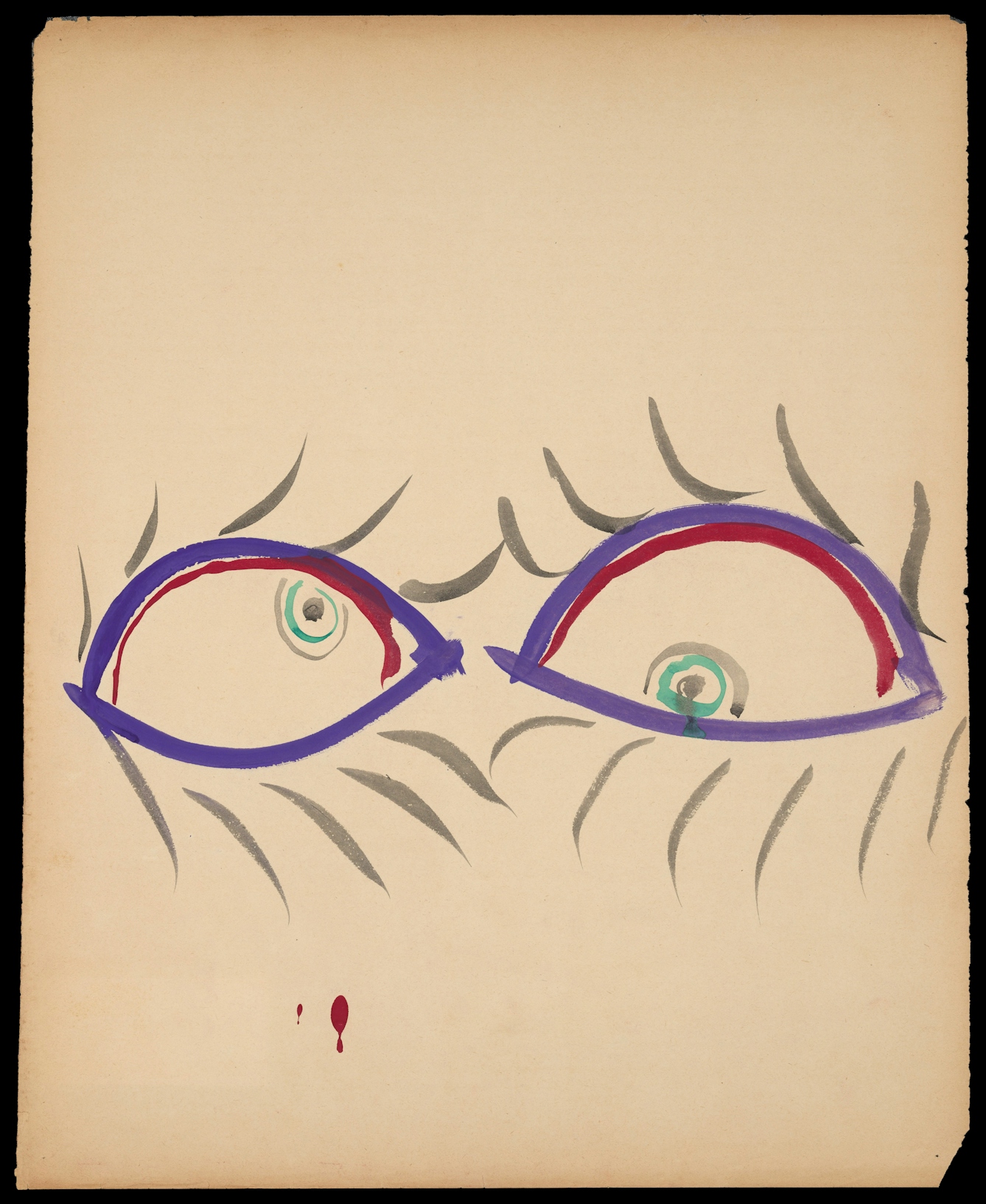

A pair of eyes. Watercolour. 1966. Mary Bishop. (Artwork titled by cataloguer for identification.)

In J K Wing and G W Brown’s book ‘Institutionalism and Schizophrenia: A Comparative Study of Three Mental Hospitals, 1960–1968’, in which Netherne features, it becomes apparent that the personal appearance of women such as Mary was used as a metric of their mental state. The ‘appropriacy’ of hairstyle and make-up were given equal weight to what interviewees said about what was happening to them and how they felt about it.

In photographs taken in the mid-1950s, by Bert Hardy of Picture Post for an unpublished feature on Netherne, many of which are incredibly intrusive, it is glaring how inured those depicted are to the surveillant gaze; uninterested in the camera and the photographer behind it. The few shots in which an individual returns the camera’s stare, defies it or expresses resistance create a frisson of shock.

A world filled with eyes

In some of Mary’s work, she expresses outrage at how little regard for her personhood the institution displayed. In ‘See the Nude Woman, Walk Up, Nothing Sacred’, she draws her naked body and horrified face on the threshold of a circus tent, where suited psychiatrists wearing aggressive expressions wait to make a spectacle of her.

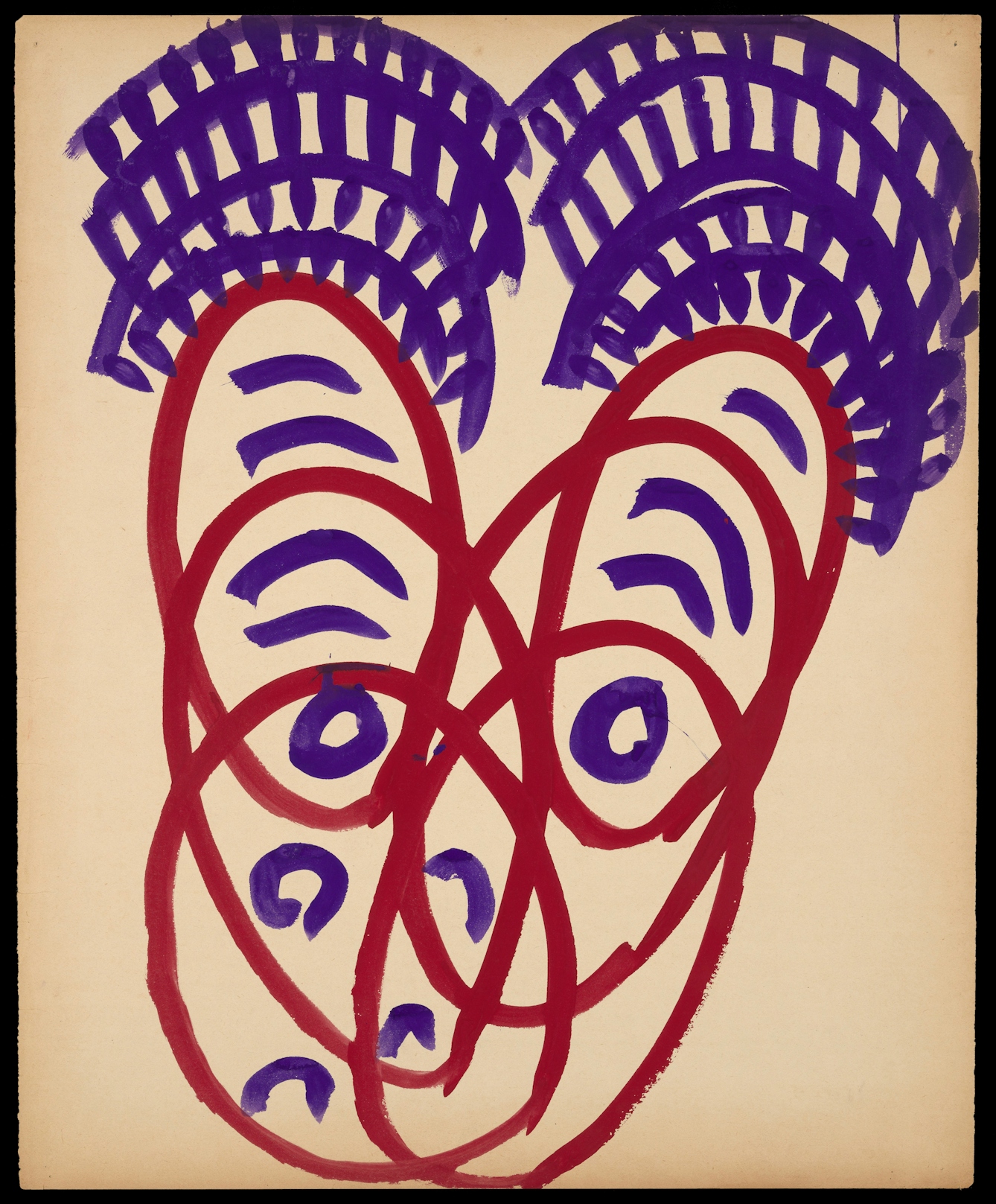

In a series known as ‘The Robot Doctors’, square-headed, white-coated medics inflict torments of whipping and stabbing, which make literal her feelings about how penetrating and punitive she found life within the psychiatric system. For Mary, though, the surveillant gaze was not only externally inflicted. Her work shows her to have been engaged in a constant process of pitiless self-scrutiny.

Two eyes combined below rounded fences representing guilt. Watercolour. 1969. Mary Bishop. (Artwork titled by cataloguer for identification.)

On the backs of her many hundreds of works, she writes short, excoriating notes to accompany what she has drawn; fragments which, taken as a whole, provide a huge amount of autobiographical and emotional insight.

Her father, a reverend of the Anglican church in Cardington, Shropshire, was killed in action at the Third Battle of the Aisne in 1918, when Mary was four. Her mother, in the grip of overwhelming grief, took her to Euston station in London to see coffins and the wounded returning from the front in order to ensure that Mary “grieve properly”.

To live at Netherne was to exist in a perpetual state of surveillance: to be examined by doctors, watched constantly by nurses, and to be accompanied everywhere, even to the lavatory.

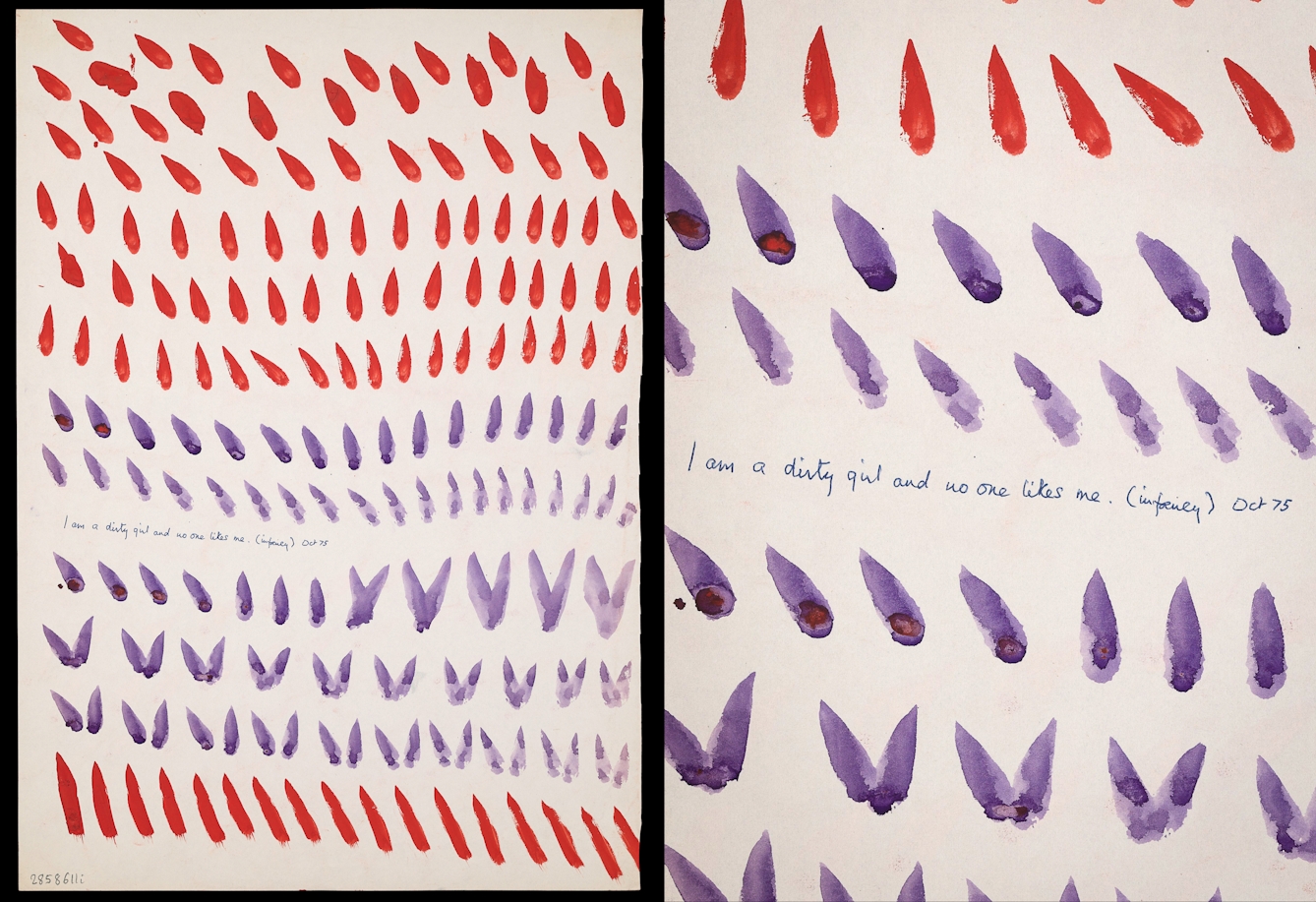

Many drawings and the accompanying notes on their backs, in Mary’s cramped, slanting handwriting, make it clear that the young Mary was made to feel that she was inappropriate and insufficient. Notes on her work bear a litany of swingeing criticism, carried through the intervening decades: “mother said I was a dirty girl, I have always been dirty, I was born dirty.”

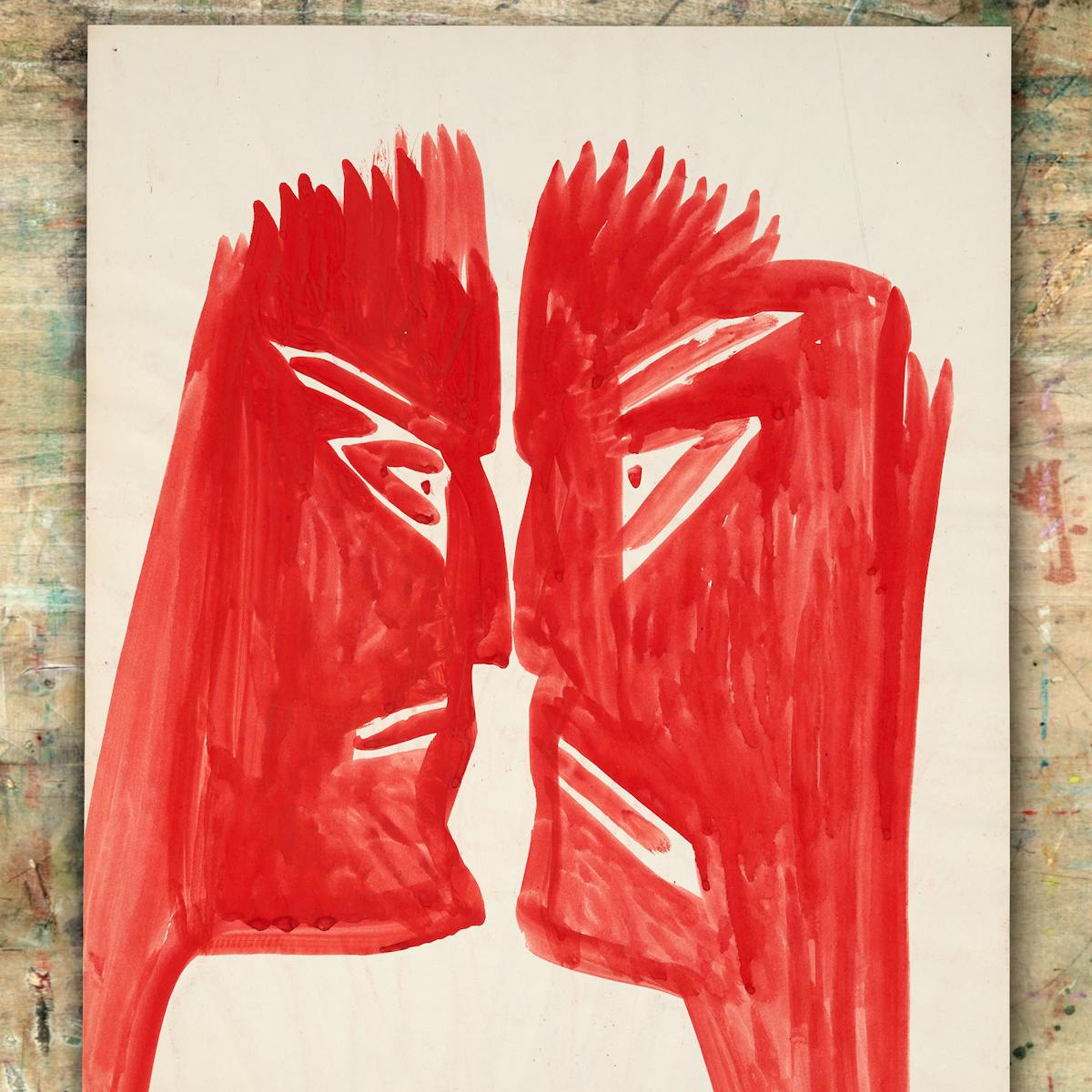

Teardrops, V-shapes and diagonals. Watercolour. 1975. Mary Bishop. (Artwork titled by cataloguer for identification.)

Her drawings and annotations make plain that she was locked into reinscribing this critical maternal voice, describing herself as unworthy of love, and viewing her outward appearance as manifesting an ugliness she believed issued from the very core of her being.

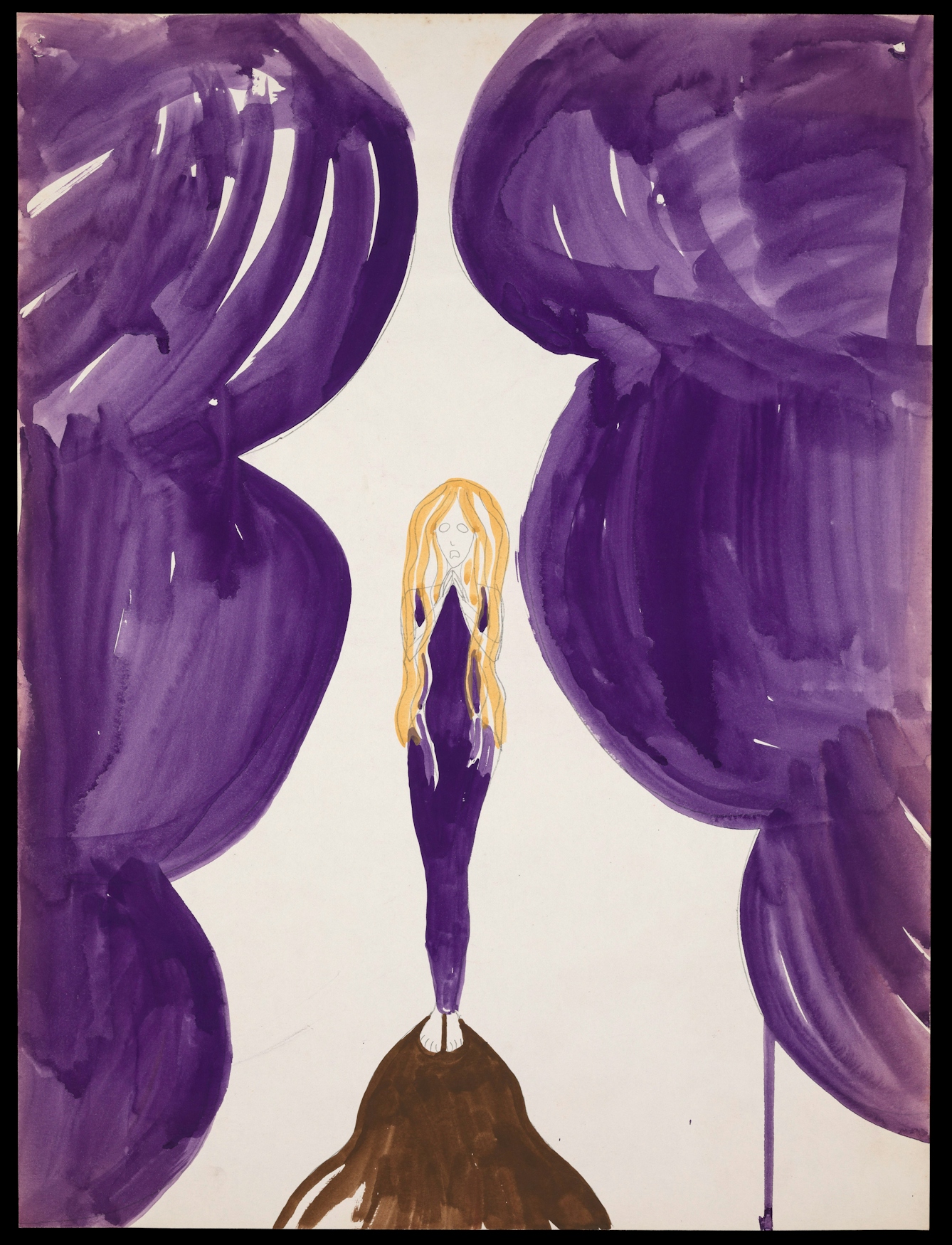

Much of her work is self-portraiture; she represents herself in multiple states of vulnerability and abjection; pale and pencilled-in, engulfed by storms of dark colour. Frequently she is loomed over by, or drowning in, surroundings which are given greater substance than herself. Her works are imbued with a sense of being beset by external forces, of always being seen, existing under the terrorising regime of a judgemental overseer. In one work even the moon is watching her with condemnatory intent.

Eyes are everywhere, rolling in agony, spiralling in confusion, wincing with self-rebuke and disgusted recoil. Howling self-portraits cover their eyes with their hands, in the attitude of a shamed child hiding, as if to protect herself from the violence of being perceived. ‘Mortification’ is the word uppermost in my mind when I look at these paintings. The most painful aspects of selfhood seem to have been brought into being by Mary’s awareness of being observed by others.

The fugitive artist

In a few brief frames from BBC documentary ‘The Hurt Mind’, filmed at Netherne in 1955, Mary is there. The filmmakers took great care not to show the full face of anyone captured on film; a compassionate act but one which also underscores the stigmatising attitude towards mental illness of the time. For a moment, her curled blonde hair and powdered cheek appear onscreen; with a brush she lays down a curved line on the figure she is painting, and then she is gone.

A woman standing barefoot on a brown rock. Watercolour. 1969. Mary Bishop. (Artwork titled by cataloguer for identification.)

No other picture of Mary exists; in several photographs of the art therapy studio, her works are visible on her easel. I find myself looking for her, to experience that specific electricity of connection, of seeing, and I am critical of my own desire to see her, as if to do so would somehow be to know her, to call her more fully into being in the act of perception.

And so I find myself relieved somehow that she proves fugitive; glad that in each picture she is absent, her presence there only represented by paintings in progress which, in the end, are the last remaining witness to her life, unguarded expressions of what she herself so clearly wanted to be understood.

Any discussion of Mary’s work invites a fundamental question about the ethics of viewing it at all. It was never intended to be shown in public, and there is a valid argument that to do so violates her privacy. In an equivalent contemporary setting her work would be destroyed as clinical waste, like anything else removed from a human by process of medicine.

A lot of her work certainly has the quality of expurgation, that which is normally hidden from our eyes. And yet it provides an invaluable insight into a life shaped by war, the majority of which was lived within an 20th-century psychiatric hospital.

It offers personal testimony to the experiences of someone who does not exist in her own words elsewhere, who belonged to a group of people who were easily ignored within their lifetimes and forgotten after their deaths. To see Mary Bishop’s paintings, to be acted on and communicated with by them, is a sharp and necessary reminder that a life overseen does not need, inevitably, to end in oversight.

About the contributors

Rose Ruane

Rose Ruane is a writer and artist.

Mary Bishop

Mary Bishop was a prolific artist who painted thousands of pictures during her 30-year stay in Netherne Hospital.