Ellie Levenson explores how medics’ views on her weight affected the way they spoke to and treated her when she sought fertility advice and during her three pregnancies. Here she recalls their words, filled with judgement and condescension, and how their assumptions impacted her.

Although I am no fan of Thérèse Coffey’s politics, when she was appointed to what turned out to be a seven-week stint in the role of Health Secretary in late 2022, I did find elements of her approach refreshing.

Criticised for being fat, smoking cigars and liking a drink, she responded by saying she’d let the Chief Medical Officer and others be the role models and that as a patient of the NHS, “I’ve had some brilliant experiences and I’ve had some experiences where it could have been better.”

I can imagine what some of these experiences may have been like. After all, it’s a bit of a joke amongst fat people that when you go to the doctor the first thing you are told is to lose weight, regardless of the issue.

Tonsillitis? Lose weight. Ingrowing toenail? Lose weight. Headaches? Lose weight. “Doctor, doctor,” the joke might go, “I’m losing weight without trying and I’m worried.”

“You should try losing weight,” the punchline might go.

What fat women know

In my early 30s I saw a fertility specialist because I had not conceived after a year of trying. I should lose weight, he told me, before they could do anything else.

I had a question for him about this. I wanted to know, if it took me a year to lose enough weight for him to consider other causes, whether the advantage being less obese would give me would be more or less than the disadvantage of being a year older.

In other words, what would be better in terms of conception – being older and thinner or younger and fatter? The doctor did not answer my question. He looked at me with pity. “Go away and try to lose some weight,” he said. He might as well have said, “Piss off, fatty.”

“It’s a bit of a joke amongst fat people that when you go to the doctor the first thing you are told is to lose weight, regardless of the issue. Tonsillitis? Lose weight. Ingrowing toenail? Lose weight.”

Some of the advice to lose weight may have been an attempt at kindness. It is possible that the doctor was suggesting I lose weight so that I fitted into the NHS guidelines on who qualifies for fertility treatment. But I had also known in advance what his advice would be. Every fat woman does. However, as fat women also know, if losing weight was easy, there would be no fat women.

I do, however, come from generations of fat, yet by definition fertile women – that’s why there are generations of us. And although I did not know it at the time, I was one of them. I did not need to go back to see that doctor. I conceived naturally, after about two and a half years of trying, and no less fat than I had been at the beginning, and I went on to have three children within five years.

But only now that my youngest child is seven have I really begun to process the impact my experiences as a fat woman had on my own conception journey and my experiences of motherhood so far.

Feeling grateful and unworthy

So much of the noise around pregnancy is about embracing our bodies and their power, and many pregnant women speak of the sense of freedom that comes with eating what they want, when they want – for some this is the first time in their post-pubescent lives that they have done this.

As a fat woman, however, medical staff took every opportunity to remind me not to do this, and to tell me that by being fat the chance of a healthy outcome to my pregnancy was smaller. I don’t dispute the science or the risks, although many of them are more significant statistically than for individuals, but once I was pregnant what possible effect could this have other than to make me feel more worried and more guilty? It was not going to make me decide not to go ahead with the pregnancy, or to want my baby any less.

As a fat woman you already feel so grateful and unworthy of many of the things other people may take for granted. You are so grateful someone loves you when you have been told by society that you are unlovable. You are so grateful to have conceived when doctors have told you that your weight is the reason for you not doing so, even though you ovulate regularly.

You are so grateful for being pregnant that you will submit to being reminded that if your baby dies, it will be your own fat fault.

“As a fat woman, however, medical staff took every opportunity to tell me that by being fat the chance of a healthy outcome to my pregnancy was smaller.”

When I thought my first baby had died a few hours after she was born (she hadn’t), and I sat numbly on my hospital bed while she was whisked away for medical attention, I remember thinking to myself that of course she had died, because I was never meant to have been lucky enough to have her anyway.

How much of this was exhaustion, how much of this was a kind of survivor guilt for having conceived after difficulties, and how much was because of the many messages about fat women being undeserving, I’ll never know.

I think, on reflection, that some of this inner voice could be quieted a little by not telling fat women they are fat the whole time, as if we did not already know this. How much better it would be for medical professionals at scans not to say, “We can’t see your womb through your tummy because you are fat,” and to simply say instead, “We’ll be able to see your womb better with a vaginal examination.”

The weight of assumptions

In my experience, fat women are also often assumed to be stupid. It is as if by showing that we do not have the brain power to control overeating impulses, we also do not have brain power for other things.

In one of my pregnancies, I was asked to go to a group workshop with a dietitian after a glucose tolerance test showed high blood-sugar levels. After a presentation, the dietitian asked whether we had any questions. Seven months pregnant, I did have a question. “If, against your advice, I decide to eat a chocolate bar, does that mean my baby will die or does that just mean I probably also shouldn’t eat a pizza for dinner?” I asked.

This kind of question is important. I would happily have given up pizza and chocolate, and anything else, to keep my child alive, but not just so that the dietitian could tick a box on their evaluation form.

“I think, on reflection, that some of this inner voice could be quieted a little by not telling fat women they are fat the whole time, as if we did not already know this.”

The dietitian did not seem to understand my question and could not give me an answer. But it’s important to make the distinction – being fat goes against societal norms but it is not the same type of outcome as having a dead baby. Everyone, regardless of size, needs to be provided with the evidence and advice to make their own risk assessments and manage their own health.

The treatment of fat women is not just about feelings. There is an impact on NHS resources too. How many appointments are needlessly given to women just because they are fat?

I was sent for one with an anaesthetist ahead of my due date. “Why am I here?” I asked. “To check you have a spine in case you need an epidural,” they replied. I think they meant to say it was to check they could find my spine, rather than whether I had one.

Another needless appointment was at a midwife-led clinic for fat women during my third pregnancy. I had more confidence by then and this time it was she who asked me the question: “Why are you here?”

“I think,” I said, “it is because I am fat.” She looked at me. “Don’t say bad things about yourself,” she said.

I gathered all my self-respect, all my mum strength, all my anger at years of being the fat woman. I remembered that I did indeed have a spine. I looked her in the eye and said, “I didn't.”

About the contributors

Ellie Levenson

Ellie Levenson is a writer, and a lecturer in journalism at Goldsmiths, University of London.

Benjamin Gilbert

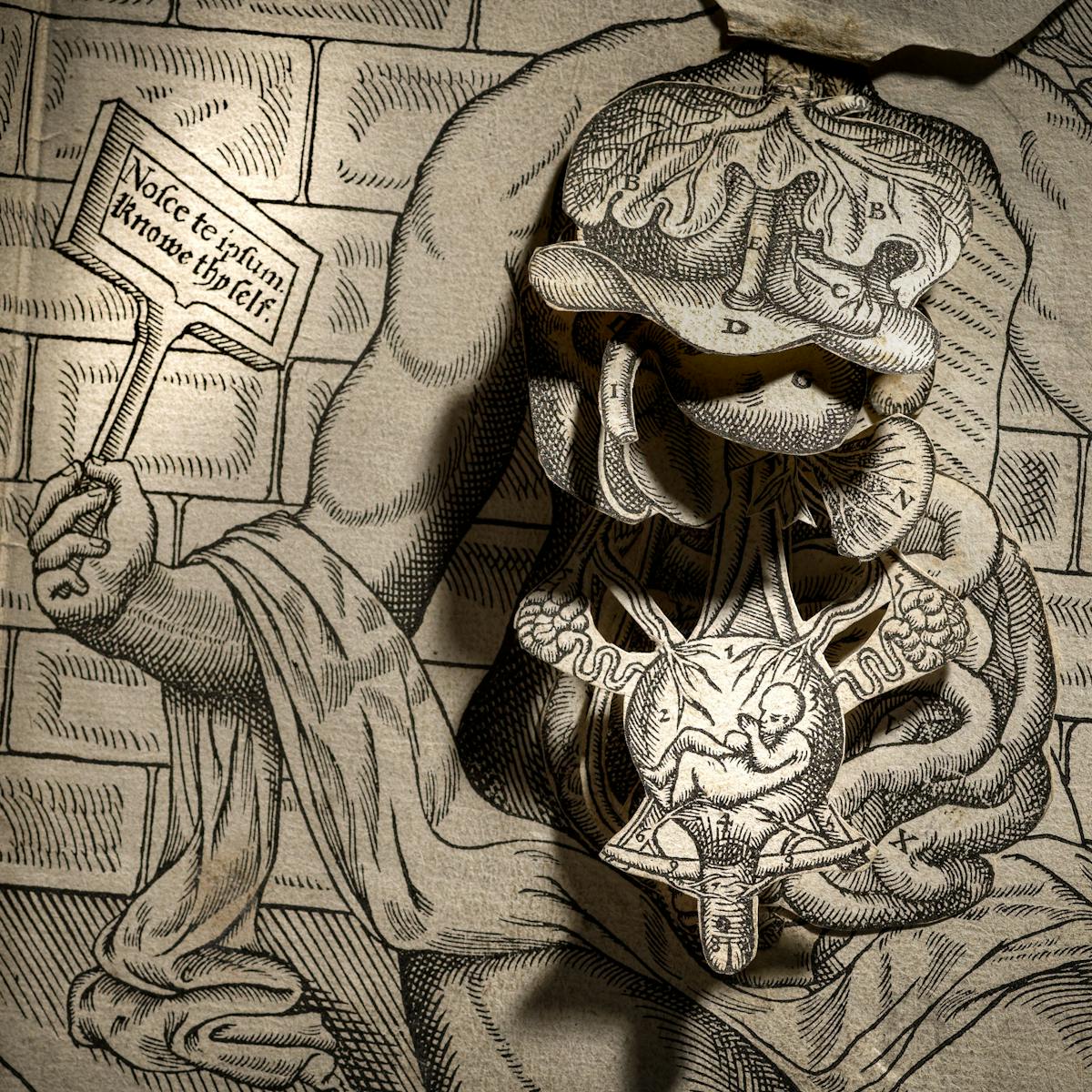

Ben is a senior photographer for Wellcome. He is happiest when telling stories with his photographs, whether that be the health implications of rural-to-urban migration in India, or the dedication of the workers who power the NHS.