Being diagnosed with type 1 diabetes as a very young child has shaped Daisy Watson Shaw’s life. Today, reflecting on others’ misconceptions of the condition, and her own teenage embarrassment and fervent wishes for a cure, she describes how medical advances have made diabetes easier to live with, and what needs to change to help others in her position.

Writing this feels like a confession, as if it’s something to be ashamed of. And that’s a hard feeling to shake. But I recognise my discomfort is rooted, mostly, in other people’s assumption that I should want to ‘cure’ my type 1 diabetes. I’m not sure if I do any more.

Type 1 diabetes is an autoimmune disorder that causes the sugar levels in your blood to become too high. It can develop at any point in a person’s life – in my case, when I was a child.

While I remember parts of my diagnosis, it’s fair to say the ordeal was hardest on my parents.

It was November 1996 – a month from my fourth birthday – when we learned the news. My naïve understanding of what it would mean was that I’d no longer be feasting on Freddo chocolate bars at Grandma’s house. Meanwhile, my parents were devastated that I had a life-threatening condition for which there was no cure.

Mum and Dad can vividly recall nurses teaching them how to give the insulin injections my life depends on by plunging a syringe into the nerveless flesh of an orange. They’d spend hours trying to coax me to eat foods I needed to keep my blood-sugar levels stable. And several times a night, they’d wake up to test my blood so I wouldn’t slip into a diabetes-induced coma as I slept.

They would have given anything if it meant I wouldn’t have diabetes any more.

Thankfully, there seemed to be a silver lining. In a room on the paediatric ward, painted with children’s cartoons, the doctors told them: “It’s likely there will be a cure within the next ten years.”

But time ticked by, and that sliver of hope never evolved into anything concrete.

Wishing for a different life

Type 1 diabetes is a disability under the Equality Act in the United Kingdom. I was told that diabetes needn’t stop me from doing anything. The truth was it did.

I’ve found accepting myself as a person with a disability to be confusing.

At school, I was both embarrassed and exhausted by my condition. Confusing it with type 2 diabetes, people would often ask if I had given it to myself by eating too much sugar or being overweight. Because of this, I felt a need to be on the defence.

I’d do everything in my power to hide my diabetes, even if it made me unwell. On a first date in my teenage years, I allowed my blood-sugar levels to rise to the point I felt sick – all to avoid injecting insulin at the table and drawing attention to my condition.

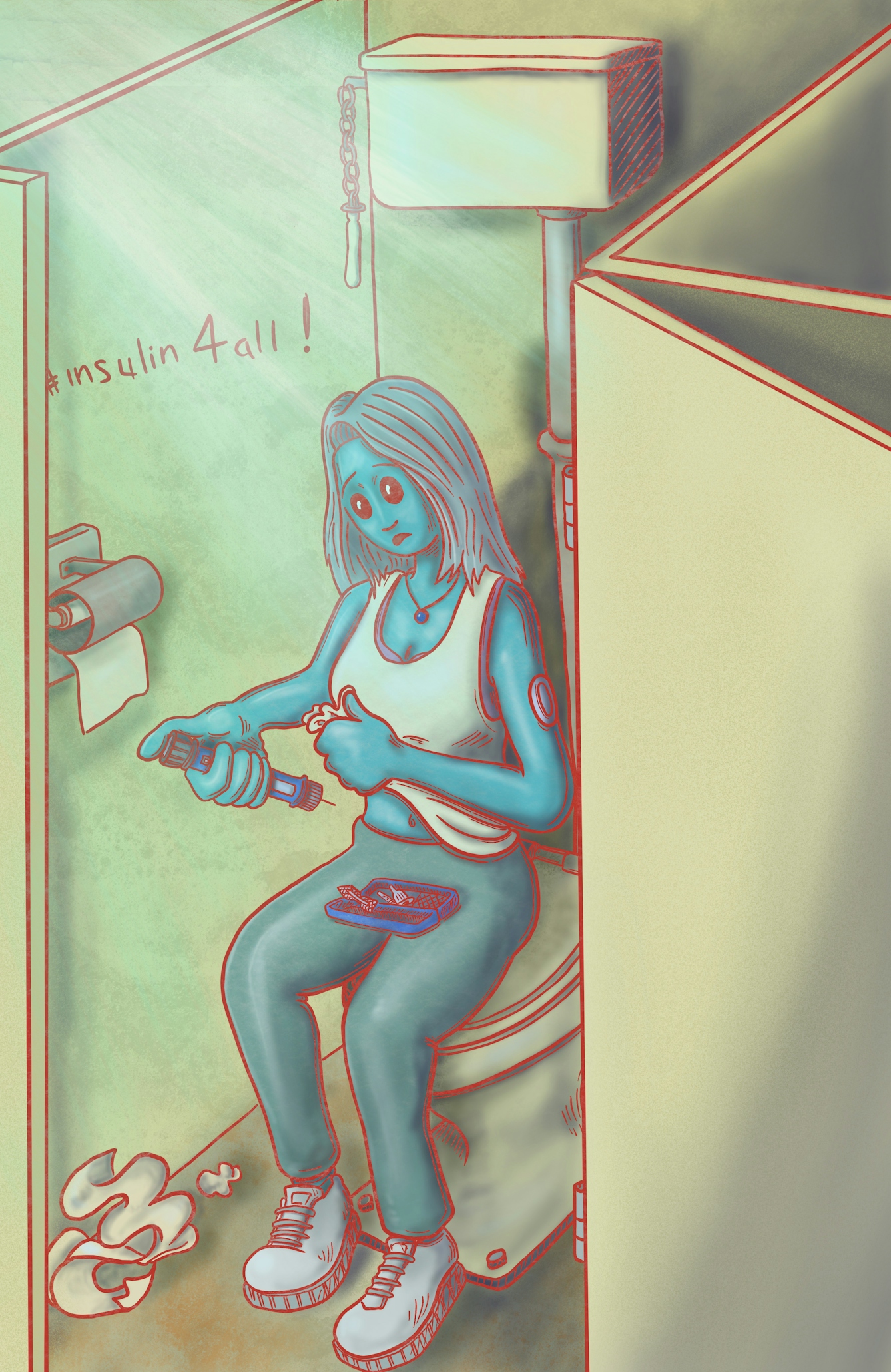

“Even now, I sometimes take myself off to the nearest toilet to do my injections – no matter how dark, grotty and disgusting – so people don’t ask questions.”

And at every birthday as a child, I’d blow out the candles out on my cake and wish for a life without diabetes. I longed to be free from the thousands of daily decisions about food, exercise and medication. Knowing diabetes can lead to blindness and loss of limbs, I was desperate to be rid of such fears.

Family members cut out newspaper articles they found with even a mere mention of diabetes, but none of them were about the scientific breakthrough we were waiting for.

Curing my diabetes was seemingly of vital importance to people I didn’t know, too. There was one time a stranger overheard me collecting my insulin from the pharmacy. As I left the chemist, he called after me with a sense of urgency. He told me he’d read an article about how eating a strict diet of raw carrots could cure diabetes and suggested I give it a go. (I didn’t.)

This stranger thought he was helping – but it caused more harm than good. It felt like a reminder that I needed to be fixed.

Questioning ‘cures’

The last time I considered what it would be like to live without diabetes, something felt different. It was at a wedding last year – and it wasn’t the “in sickness and in health” part that prompted it.

My quality of life has improved over the years – and with it, my outlook on a future with type 1 diabetes.

As often seems to happen, I somehow managed to sniff out another person in the room with type 1 diabetes. We talked about the balancing act it requires to survive, as our friends slipped away to start a separate conversation – one that didn’t revolve around a chronic health condition – as they sipped Prosecco.

“I’m kind of running out of hope, but I really hope they find a cure in our lifetime,” he said. Like a well-rehearsed line in a play, I replied, “Me too.” But, as I said it, I realised for the first time my feelings on curing type 1 diabetes had changed.

For one, my quality of life has improved over the years – and with it, my outlook on a future with type 1 diabetes. The changes I’ve experienced have often seemed small or insignificant, but I now see what a huge difference they’ve made.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s still isolating at times. Even now, I sometimes take myself off to the nearest toilet to do my injections – no matter how dark, grotty and disgusting – so people don’t ask questions.

But I consider myself very lucky to have benefited from new education programmes, treatments and technologies which help to manage it. Especially when the global health inequalities for millions of people with diabetes are fatal, with barriers to insulin access being the most common cause of death in children with type 1 diabetes. That’s heartbreaking.

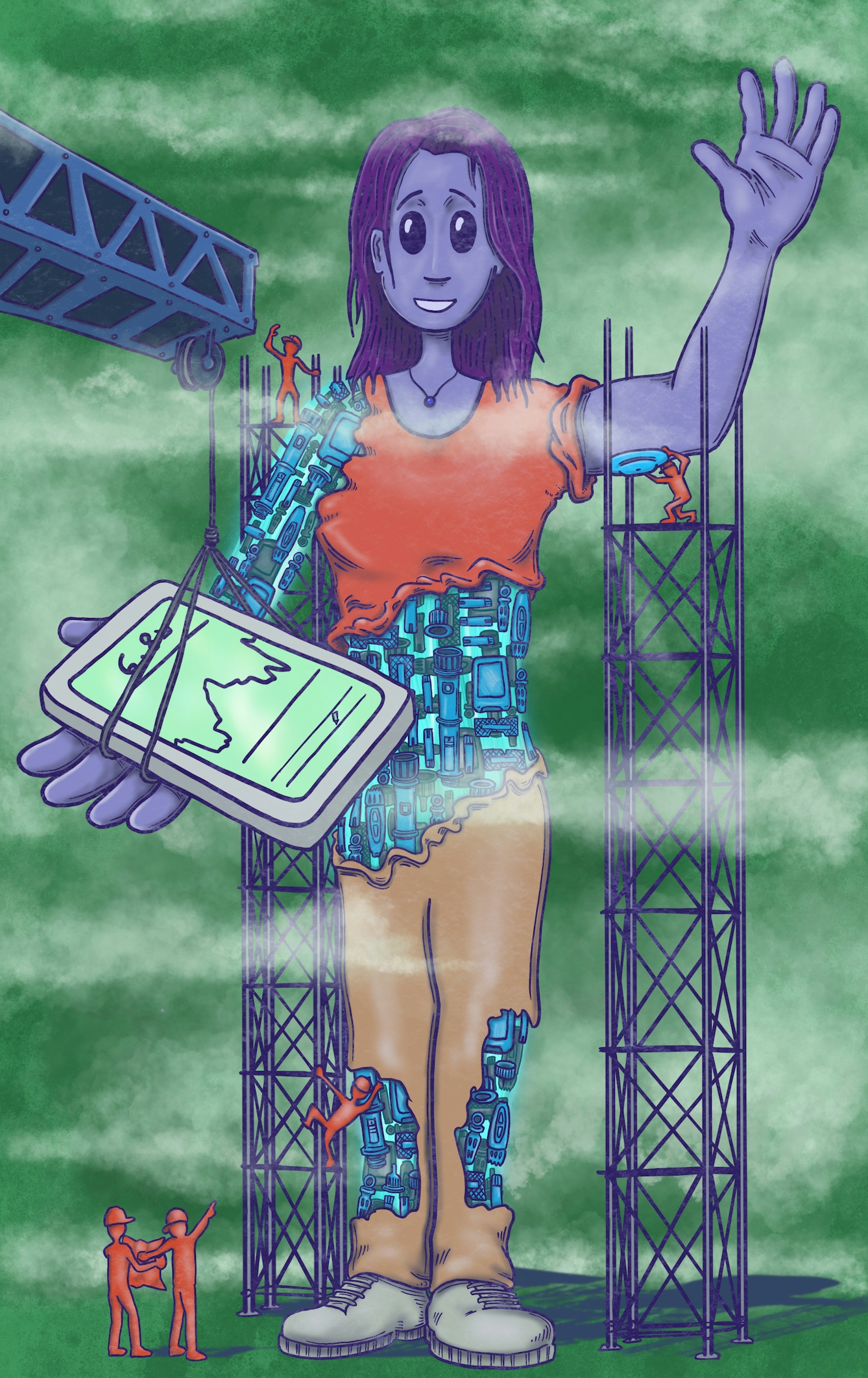

In recent years, I’ve been able to access ultra-rapid-acting insulin therapies to help combat high blood-sugar spikes. And I now wear a continuous glucose monitoring sensor to get real-time glucose readings on my phone.

And while I don’t feel defined by diabetes, I know it’s shaped me in positive ways. When I was presented with a “I can do my own injections!” certificate at five years old, it didn’t feel like something to celebrate. But, looking back, I’ve had to be responsible from a very young age.

I’ve also made friends with other diabetic people, simply because we’re connected by shared experience. Now, thanks to continuous glucose monitoring technology, the summer months are spent playing “spot the sensor” as people with diabetes bare their skin to the sun. And I feel part of a community as others spot mine too. On a night out, I even shared a portion of fries with a stranger after bonding over the blood-testing device.

“I’ll pray for more awareness of how to support people like me in our communities.”

Life with type 1 diabetes isn’t inherently bad. The way society prioritises and funds ‘cures’ for disabilities like mine is the real problem: it prevents us getting the support we really need. Instead, money could be spent developing better treatments and accessible spaces for all.

Pride in my condition

Next time I make a wish, I won’t be conjuring dreams of a future without diabetes.

Instead, I’ll hope for significantly increased access to closed-loop systems, so people with diabetes don’t need to make as many decisions and risk burnout.

I’ll keep my fingers crossed for safe, clean, dignified places for us to inject our insulin.

I’ll imagine media presenters distinguishing between diabetes types to avoid misinformation.

I’ll pray for more awareness of how to support people like me in our communities. People with type 1 diabetes can be up to three times more likely to experience depression than the general population. The compassion and understanding from those around us could be a lifeline.

I want a better quality of life for people with diabetes, and for everyone who needs insulin to be able to access it.

If all of this were to come true, I can begin to envision a world where I never longed for a cure in the first place.

About the artwork

The series reflects the balancing act between embracing life and living with a chronic disease felt in Daisy’s article and Tony’s own experience of living with type 1 diabetes, and the tension between the hope for a cure and the desire to experience life fully now.

Tony is interested in making the invisible visible: the idea that the body is no longer able to manage itself; the technology of “the cyborg” (the “diaborg”); and medical waste as both an intrinsic part of treatment and an environmental issue at the same time. The images consider the issues that Daisy raises of confusion, the shame and potential that living outside-in with your body all entail.

Tony’s work questions notions of bodily autonomy and identity that are raised in becoming a person (/patient) living with diabetes, and the ways in which art and graphic medicine can provide a pathway for better patient interaction.

About the contributors

Daisy Watson Shaw

Daisy Watson Shaw is a writer and poet who is grateful to have been adopted by Yorkshire. She loves writing as a means of exploring and experiencing relationships with ourselves, others and the world around us, in new ways. She currently specialises in copywriting within mass communications for a global humanitarian organisation.

Tony Pickering

Tony Pickering is an illustrator/artist and creator of the graphic pathography ‘Diabetes: Year One‘. His fascination is the arena of graphic medicine – where the comics medium intersects with patient and practitioner experiences to illuminate our understanding of illness, and the implications it can have for a patient-focused approach to health communication, visualisation and interaction. He has developed a freelance practice focused on patienthood, community histories and narratives, further expanding into exploring concept design, mapping, data visualisation and sketch-noting to facilitate discussion and debate.