When facing this work, there is a yellow fabric bench behind you. The bench has back and arm rests.

Hi, it’s Cindy Sissokho again, the curator of ‘Hard Graft’.

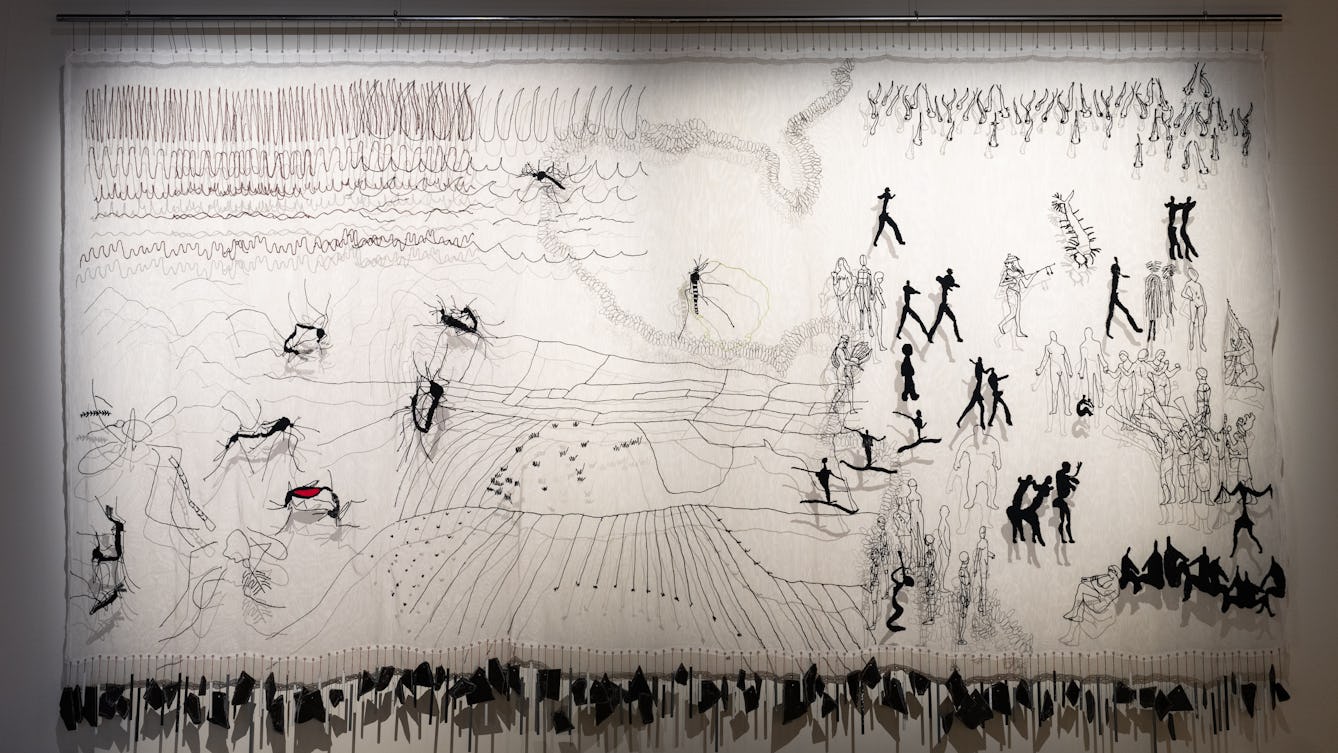

Mosquitoes and humans gather around a central sugar-plantation field. Their encounter is boldly embroidered in black cotton thread on a vast, translucent white mosquito net, hanging over 2 metres high by 4 metres wide. The mosquitoes swarm on the left side of the textile; the plantation spans the centre; and the humans fill the right side of the textile. The mosquitoes are almost the same size as the humans, and some of the humans’ bodies are elongated, echoing the mosquito forms. The net is lit so that the embroidered figures cast shadows onto the wall behind, creating a ghostly imprint.

Artist Vivian Caccuri lives in Rio de Janeiro, in Brazil, where mosquitoes are a constant presence. Transported from Africa by European slave ships starting from the 16th century, mosquitoes carrying yellow fever, malaria, dengue, and other diseases thrived in Brazil’s sugar plantations. Epidemics of mosquito-borne diseases were a product of colonialism, but also a major obstacle to it, and efforts to control these diseases led to the beginnings of tropical medicine. Today, mosquitoes continue to flourish as the world’s biodiversity declines.

Caccuri invites us to imagine a different relationship with mosquitoes, in which we share an environment as equals, and learn to respect the power these tiny creatures have to shape our world, from the design of our cities to our genetic code.

On the left side of the textile, a dozen mosquitoes tangle in pairs, their thick black bodies and spindly legs entwined. They are mating, but their poses also give the impression of dancing or fighting. One’s stomach is swollen with bright red blood, a spot of colour in the monochrome scene.

A plantation landscape spans the centre of the textile like an empty battlefield. Gentle hills are divided up into fields and planted with strict rows of crops. A lone male mosquito travels across this zone, gangly legs outstretched, surrounded by a faint green line. Male mosquitoes need sugar to survive and reproduce, and sugarcane plantations offer a plentiful supply.

On the right side of the textile, the humans gather in clusters. Some are black silhouettes; others are outlined. Together they represent Brazilian people as being of Indigenous, African and European descent. Some are naked with exaggerated round backsides, full thighs and dangling breasts, or flapping penises. Others wear plumed headdresses and cloths around their waists. Small groups sit on the ground, backs resting against each other. More dynamic pairs dance, accompanied by musicians.

Caccuri’s fascination with mosquitoes began with their sound. Why does the mosquito’s whine – made by the rapid flapping of their wings – trigger such feelings of irritation and repulsion? Does this fear have a colonial origin? At the top left of the textile, the sky is a-buzz with scrawny soundwaves – we can imagine the high-pitched hum of these quivering lines. Near the centre of the textile, they are crossed by a swarm of spiralling mosquito eggs that winds its way from top to bottom, threading through the humans like the trail of a mosquito on the hunt. At the top right of the textile, a gathering storm cloud of mosquito larvae threatens to rain down upon the humans.

Hanging along the net’s hem are about 150 angular fragments of slate and slender aluminium tubes, each roughly 10 cm long, hovering like wind chimes just above the floor. Caccuri collected these cast-off materials during walks around the city streets. Slate is a common building material in Rio, and aluminium chimes are used in samba – an Afro-Brazilian music style that expresses both resistance and joy.

This is the end of Stop 6.